Source: gallica.bnf.fr; Bn lat. 190, f. 44r

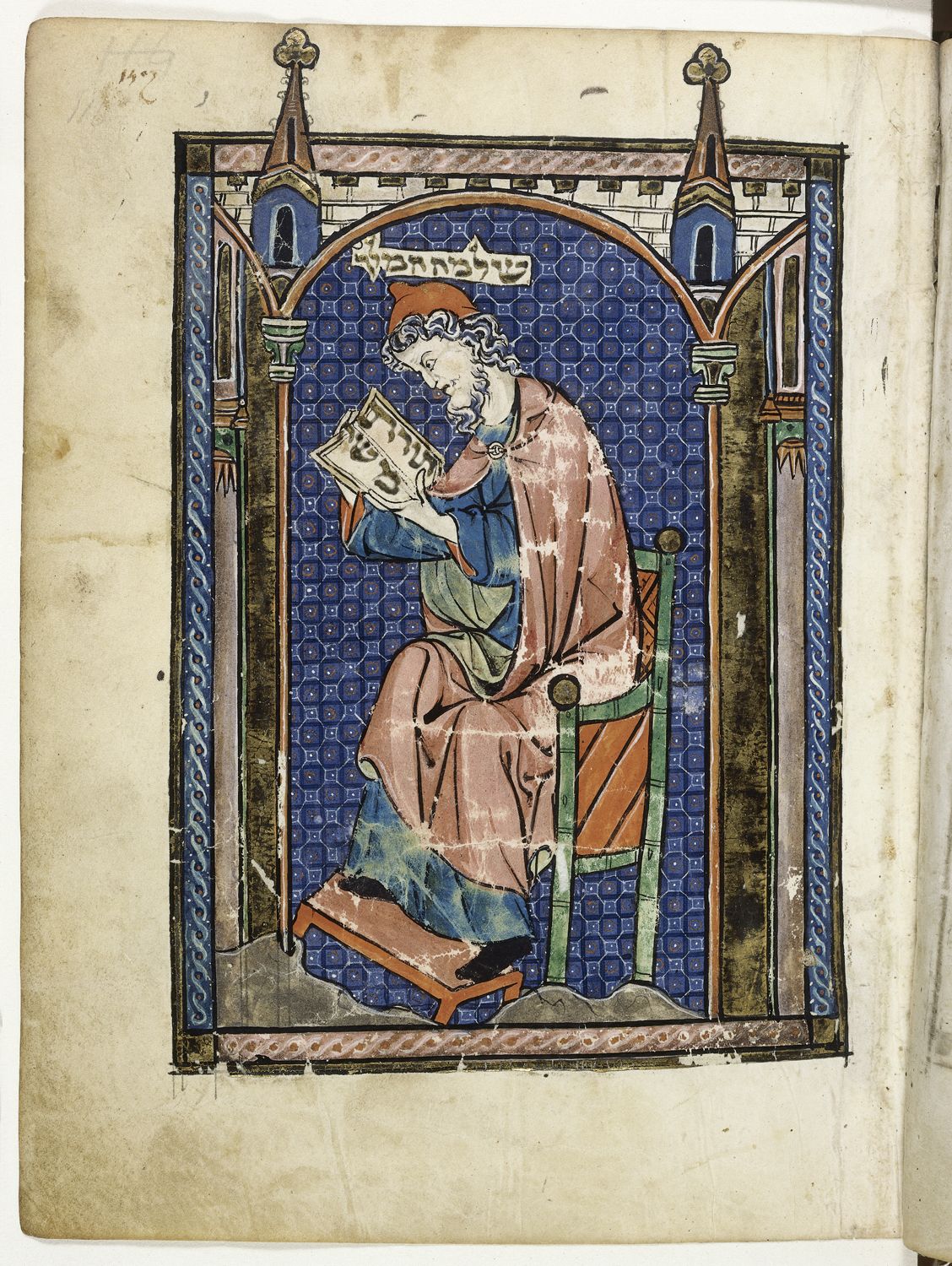

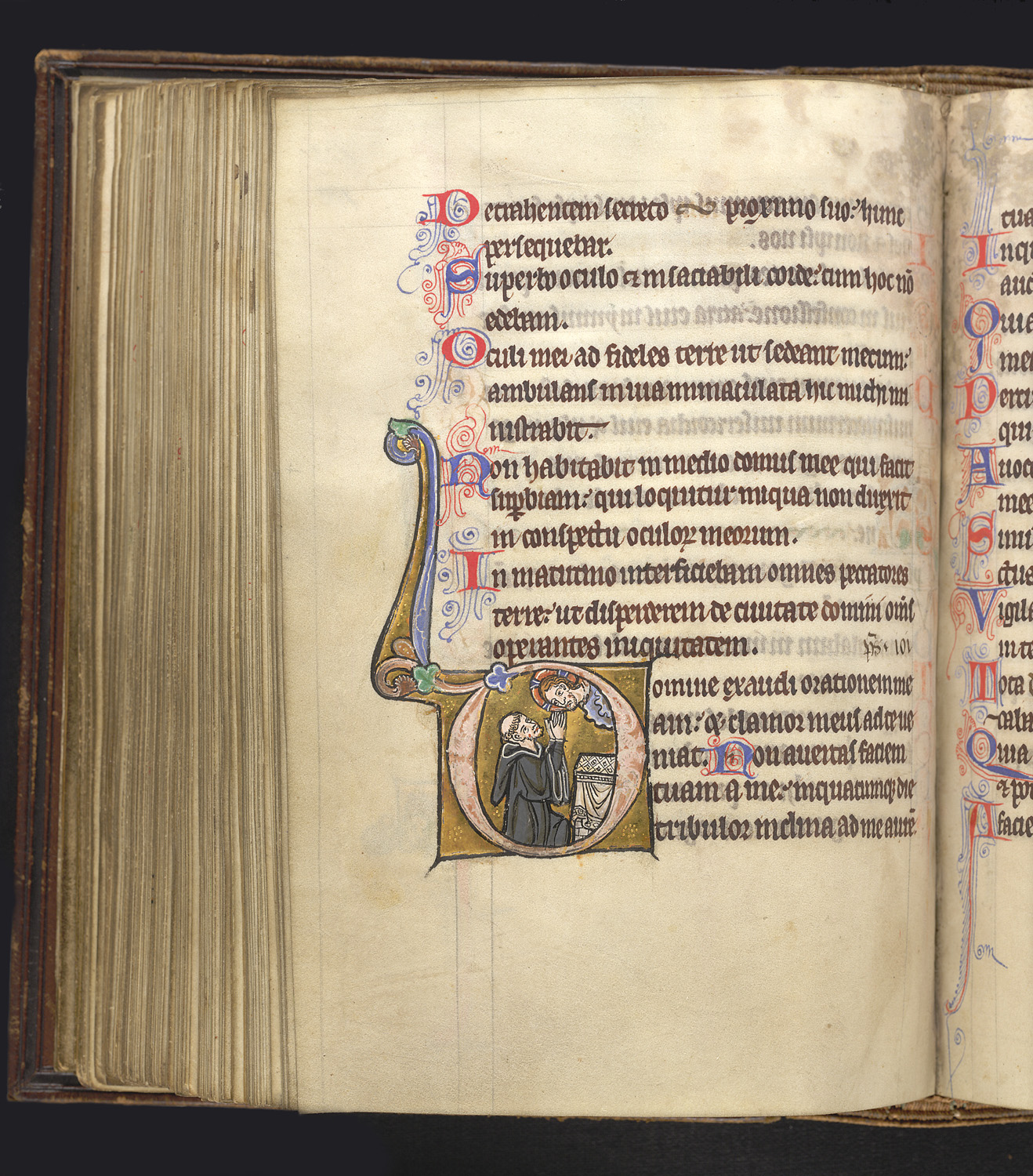

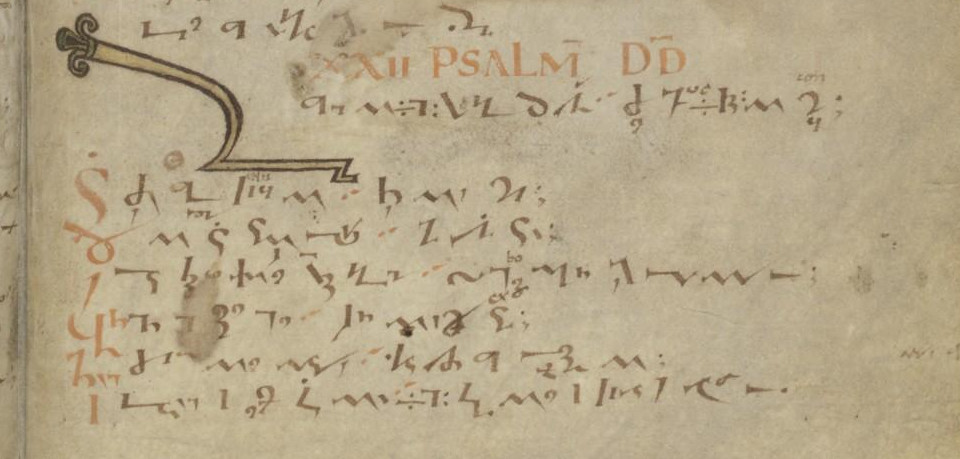

Medieval manuscripts pose many intriguing writing systems. Some, like Yale University’s Voynich Manuscript have foiled even the best attempts to unravel them. Others, like this strange looking text from the Bibliothèque nationale de France may seem to have come from another galaxy, but it can actually be identified from its rubric letters XXII PSALM[US] D[AVI]D, the twenty-second Psalm! (Psalm twenty-three in modern bibles)

Although it looks like the lost script of ancient aliens, this strange writing system is actually a medieval form of abbreviated writing known as Tironian Notae. Tradition ascribes the invention of these strange squiggles to the Roman Senator Cicero’s freedman and secretary, Tiro. Tiro, so it is claimed, developed this way of writing to help him take down his employer’s verbose dictation more quickly. This system of shorthand is attested in the ancient world, but was adapted and used extensively among the esoteric intellectuals at the courts of Charlemagne and his Frankish successors. Large numbers of manuscripts written partially or sometimes entirely in Tironian notes survive from this period (roughly 750-900 CE). Carolingian court scholars and bureaucrats seem to have been attracted to this writing system’s facility for writing everyday documents, but entire books were composed in it. They even adapted the script by adding new symbols to quickly write Christian words like “Prophet” or “Holy Spirit.”

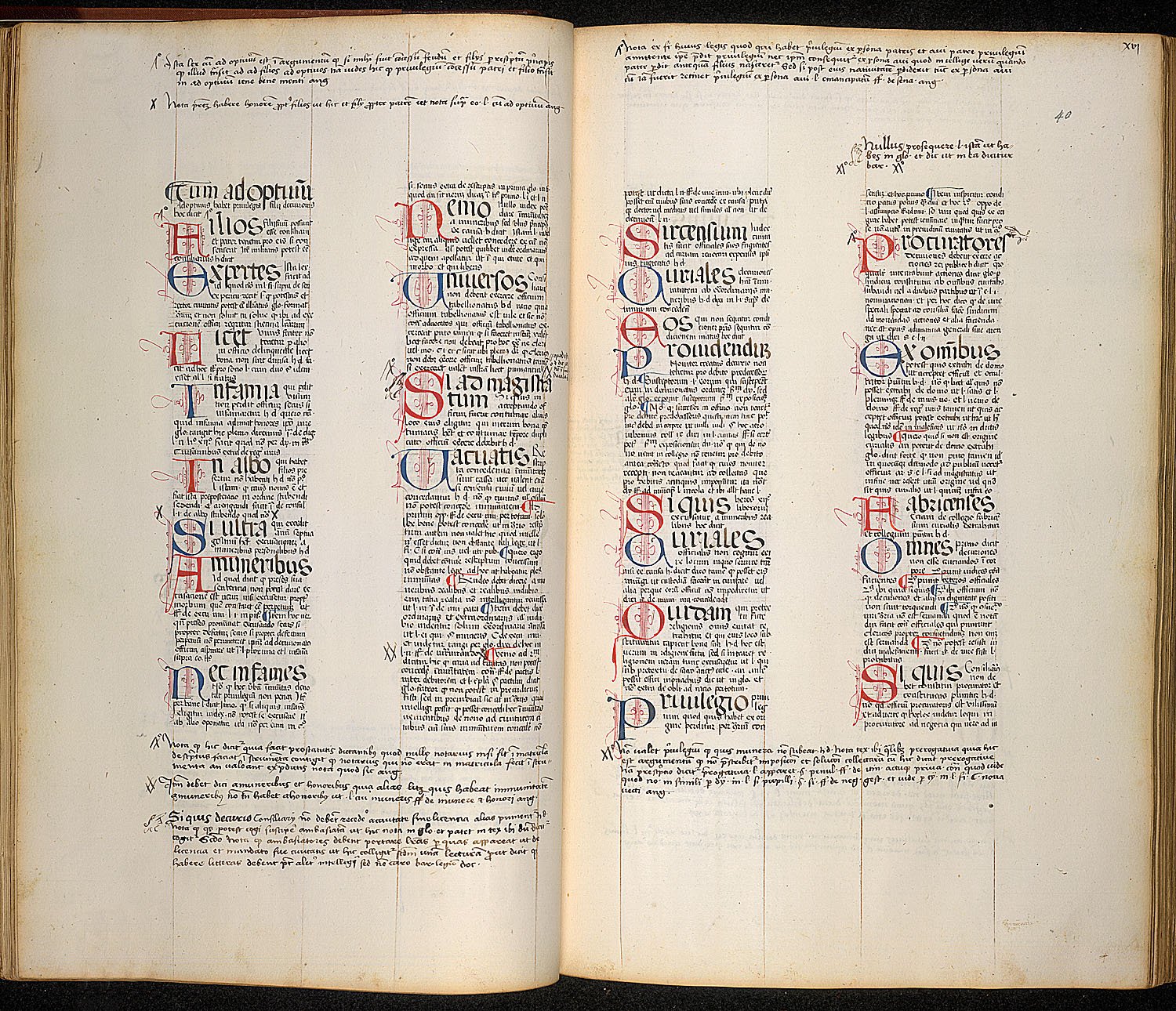

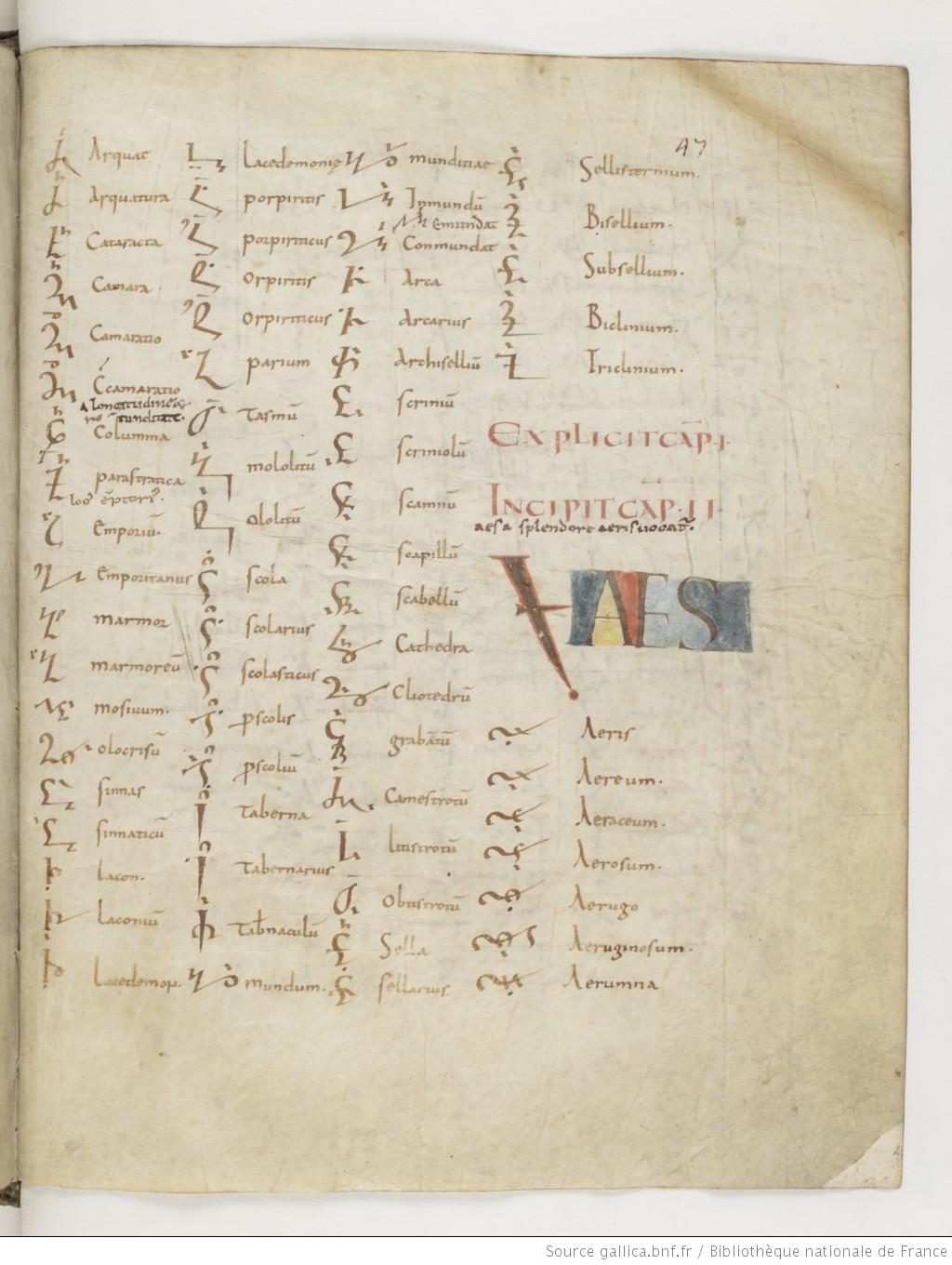

Source: gallica.bnf.fr; Bn lat. 8779, f. 47r

Very few everyday records have survived in Tironian script. One type of texts that do survive, however, are textbooks used to teach the Tironian system to new scribes. Large texts like the Psalter above written entirely in Tironian Notae gave students the opportunity to practice deciphering the script, while dictionaries and word lists like the one below presented the vocabulary in groups based on shared roots. A careful examination of one set of words below demonstrates the way the Tironian shorthand was based on variations to a common root. The set of four symbols shown below stood for the Latin words:

‘aereum,’

‘aeraceum,’

‘aerosum,’

‘aerugo.’

Although knowledge and use of Tironian shorthand disappeared rapidly during the decline of Carolingian court culture in the tenth century, aspects of the system were preserved in part by incorporation into the standard long-hand forms of writing Latin. The Tyronian note looking like ‘7’ was frequently employed in normal Latin writing to represent the word ‘et’ (‘and’). In England especially, Tironian ‘7’ was so popular for writing the Latin word for the conjunction that scribes even used it for the native English word meaning the same in Anglo-Saxon and Middle English texts.

Although the vitality and importance of this ancient writing system were quickly forgotten, books like this Paris manuscript are tangible reminders that what we might consider the “dark ages” was actually a time of sophisticated learning and culture which preserved and extended a form of literacy so sophisticated it looks alien to us.

Benjamin Wright

PhD Candidate

Medieval Institute

University of Notre Dame

This post is part of our ongoing series on the Mysteries of Medieval Codicology.