Pairing myriad traditional dishes with more elaborate fare in a spectacle appealing to both sight and stomach, the modern Christmas meal maintains some semblance of the medieval feast. But modern feasts are minuscule meal events by medieval standards.

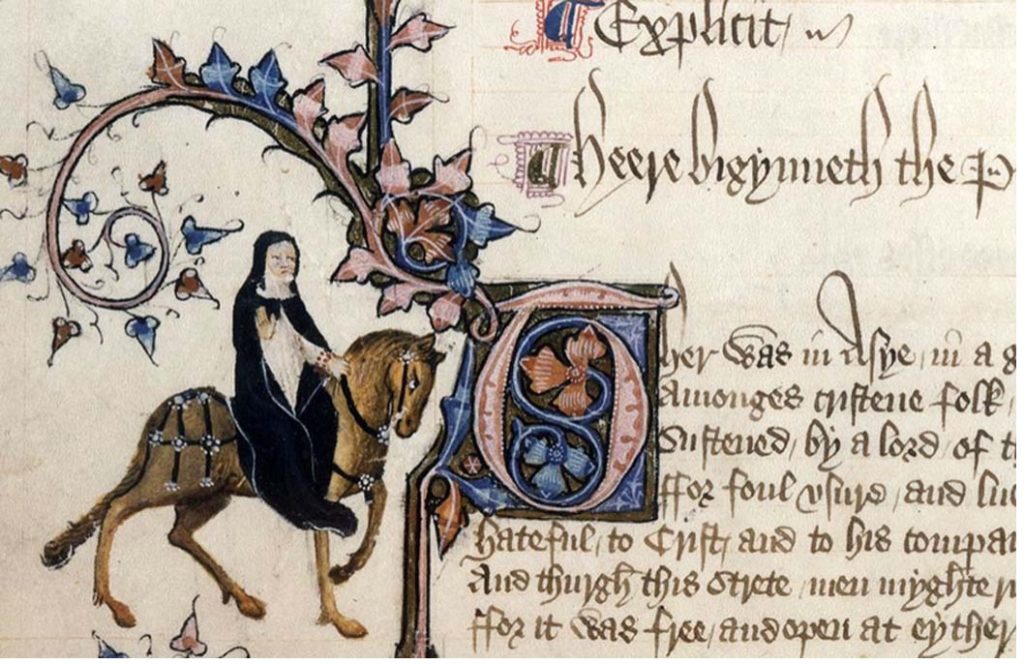

Like the feasting accoutrements of medieval England, contemporary Christmas table settings typically include cloths and candles, serving platters and salt, a plethora of foods to sample and savor. Differences, of course, also abound. For example, while we pile food upon plates and tuck into our dinners with a fork, our predecessors preferred a hearty slab of bread and a spoon.

Bread was not only served for eating but also used as crockery: large, typically square slices of bread called trenchers were used in place of dishes and, after absorbing drippings from the feast, were refurbished as sop in wine or milk or given as alms to the poor.

Medieval diners would have primarily used their fingers, plus a spoon supplied by their host for soft foods such as soups and puddings. A knife, frequently one of their own, would be used for lifting meats from platters and sometimes to the mouth. The lack of utensils does not indicate a lack of etiquette. On the contrary, table manners were held in high regard, as was hygiene. Napkins were pinned around the neck or placed in the lap. Particular fingers were used for particular foods to avoid tampering. Hands were washed in perfumed water before the meal began, between courses, and at the meal’s end.

Pageantry was an integral component of the medieval feast. Peacocks, a medieval delicacy, were cooked and served readorned with their iridescent feathers. Live birds were tethered in pies so that they sang when the crust was cut. Mythical creatures from medieval bestiaries, such as the cockentrice, were created by cooks who stitched together the upper half of a chicken and the lower half of a pig or vice versa. Performers of various kinds popped from enormous puddings, enacting a grand entrance that was itself a form of entertainment.

As guests imbibed in food and drink, musicians provided vocal and instrumental accompaniment to the feast. Music not only created appropriate atmosphere for the meal but also signaled the start of each course, even the introduction of specific dishes. Indeed, the staging and procession of the meal was as crucial for a successful feast as the food.

In the recipe for a medieval feast, time is the essential ingredient.

By medieval weights and measures, we simply don’t spend enough time at the dinner table. Modern menu plans and eating practices, even when expanded and extended for the purposes of holiday celebration, tend to follow a fairly straightforward appetizer-entrée-dessert trajectory that lasts maybe an hour or two around the actual table. Formal seating might be limited to the main course, or all three courses might be served simultaneously, resulting in an abbreviated eating experience that could not compete with the gastronomic pleasure produced through the successive courses of a medieval feast.

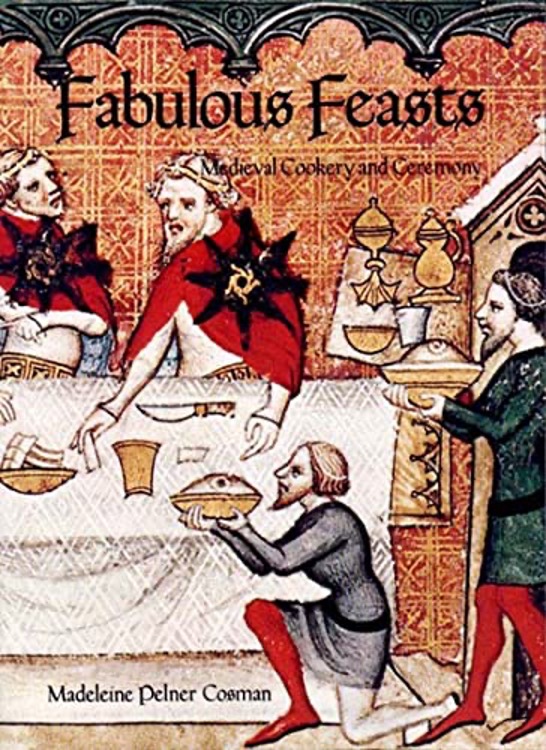

As Madeleine Pelner Cosman explains in her book Fabulous Feasts: Medieval Cookery and Ceremony, “The medieval ‘course’ was closer than the modern to the Latin origins of the word currere, to run, a running, passing, flowing ordering in time. No mere appetizer-entrée-dessert sequence made the medieval menu. Yet there was a tripartite configuration for most feast fares: each of three ‘courses’ had seven or twelve or fifteen separate meat or poultry or fish or stew or sweet dishes—or, in the most elegant feasts, all. The medieval course, then, was an artful succession of foods in time.”[1] Abundance, not gluttony, was probably the goal. In other words, medieval feasting was likely more about a wide variety of choices rather than excessive portions.

Should the pageantry of peacock preparation evade your palate or your price point (or violate the laws where you live), there are still plenty of ways to infuse the flavor of medieval feasting into your Christmas meal.

For a condensed but comprehensive feast in medieval form, you can plan your menu by preparing a single dish from each of the categories Cosman outlines in her truly excellent book: appetizer; soup or sauce or spiced wine; bread or cake; meat; fish; fowl; vegetable or vegetarian variation; fruit or flower dessert; spectacle or sculpture or illusion food.[2]

Fruit desserts are plentiful in the modern period; flower desserts are not nearly as prevalent. I highly recommend a rose pudding if you’d like to give a medieval recipe a go.

For a contemporary spin on the cockentrice, a turducken could fulfill the final category and create the kind of wonder apropos of a Christmas celebration. Remember you can always buy a three-bird roast already prepped, rather than attempt the stuffing method yourself.

Since I’ve not made a turducken myself, I can’t attest to its difficulty. But I can say from experience that a beef wellington might be a more practical choice, and the pastry can be shaped to satisfy the sculpture aspect of the category. Done properly, the beauty of the red meat inside a golden pastry crust adorned with seasonal designs is an impressive spectacle despite its relatively simple preparation. And it tastes absolutely divine.

Cue music to set the mood. If you’re interested in medieval music, you might enjoy this playlist by a friend and fellow medievalist made specifically for the holiday. I recommend Hildegard von Bingen’s Canticles of Ecstasy. If you’re medieval curious but want something more upbeat, try Hildegard von Blingen for a premodern spin on pop music.

But to truly revel in the zeal of the medieval feast, take your time. Sit at the table, serve your food in courses, and savor every minute as much as every bite.

Emily McLemore, Ph.D.

Department of English

University of Notre Dame

[1] Madeline Pelner Cosman, Fabulous Feasts: Medieval Cookery and Ceremony, New York: George Braziller, Inc. (1976), p. 20.

[2] Cosman, Fabulous Feasts, p. 130.