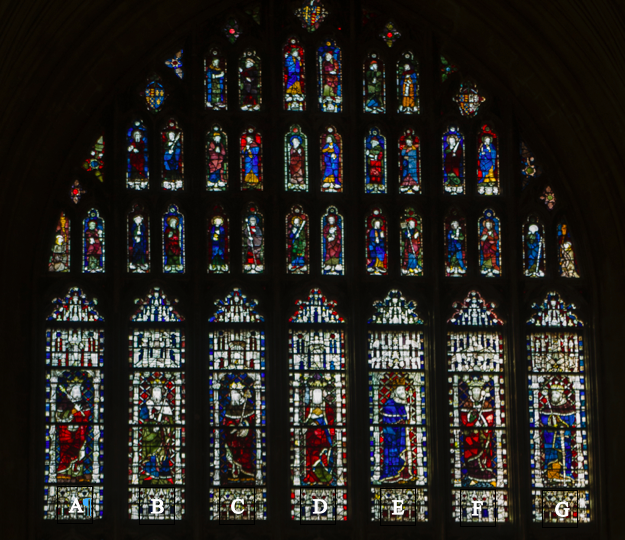

In the West Window of Canterbury Cathedral, ranged below the arms of Richard II and assorted depictions of saints and prophets, is an apparently incomplete series of portraits of English kings whose identities have become confused or forgotten over the centuries. Current attempts to identify these kings rely in part upon the eighteenth-century testimony of English historian William Gostling, who could apparently see in the window more than is visible today:

In the uppermost range of the large compartments are seven large figures of our kings, standing under gothic niches very highly wrought. They are bearded, have open crowns on their heads and swords or sceptres in their right hands. They have suffered, and been patched up again, and each had his name under him in the old black letter: of which there are very little remains. These seven are Canute, under whom remains Can. Edward the Confessor holding a book, under him remains Ed. Then Harold. William I holding his sceptre in his right hand, and resting it transversely on his left shoulder, under him remains …mus Conquestor Rex. Then William II. Henry I. Stephen. The tops of the canopies are all that are left of the fourteen niches of which the two next stages consist: if these were filled in the same manner, the series of kings would finish with Richard III.[1]

Gostling’s descriptions have proved difficult to match up with the window as we now have it. Any lettering visible in the eighteenth century has disappeared, and at least some portraits are not in the order they once were. According to Gostling’s account, the fourth king (D) should be holding a scepter in his right hand and resting it on his left shoulder: he does not. Nor can the king in position B today be imagined as “holding a book.” So William I (once D) and Edward the Confessor, at least, must have moved between Gostling’s time and now.

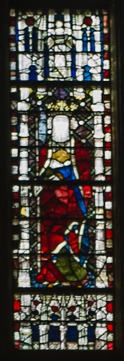

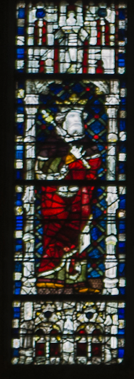

B holds a sword in his right hand, which he rests on his left shoulder–this may be Gostling’s William I. If D made a simple swap with B, it would follow, as some scholars have assumed, that today’s D is Edward the Confessor. But the king who now stands in that position holds an emblem not elsewhere associated with Edward: a prominent axe.[2] Instead, Edward might be more usually imagined as here in the famous Wilton Diptych, where he stands alongside Edmund Martyr and John the Baptist in support of Richard II, who commissioned the West Window. Interestingly, scholars have noted similarities between the styling of Edward in the diptych and the king in position A on the West Window, accepted since Gostling’s time as Cnut the Great, the Scandinavian king of Anglo-Saxon England. Despite detailing the similarities between the two, including their forked beards and long sleeves,[3] no one has suggested that this might be Edward himself rather than an Edward-inspired Cnut.

But why not? The king of the “Cnut” window (position A) might seem from afar to be holding a book-like object in his left hand (upon closer inspection it is part of his clothing). This may, nevertheless, be the otherwise-unidentified “book” to which Gostling refers in his description of Edward. Besides the marked similarities between the Edward of the Wilton Diptych and the “Cnut” of the Canterbury window is the problem of the inexplicable axe or halberd found in “Edward’s” hand. In fourteenth-century Anglo-Norman art, likely under the influence of contemporary depictions on altar frontals, glass, and panel screens of fellow Scandinavian king St. Olaf of Norway, Cnut was the only king of England imagined as carrying an impressive axe!

In a recent Alumni Spotlight on the Medieval Institute website, Notre Dame alumna Rachel Koopmans estimates that one in three of the glass narratives of the miracles of Thomas Becket in Canterbury Cathedral are misattributed. I wonder if here we have another case of mistaken identity in the Cathedral’s glass, this time of kings! If we are ready to accept that at least some of the portraits of English kings have shifted places since Gostling’s time, why should we be bound to accept that Cnut has not moved from position A since the late eighteenth century? The iconographic evidence surely supports a different conclusion.

Rebecca West, PhD Candidate

University of Notre Dame

[1] It is unclear how Gostling identifies Harold, William II, Henry I, and Stephen. Are they labeled with the “old black letter”? Or do they simply fill the pattern in the series of fourteen kings from Cnut to Richard III that Gostling envisions? William Gostling, A Walk in and about the City of Canterbury, New ed. with considerable additions (Canterbury: William Blackley, 1825), 343–44.

[2] “The position of his left hand, slanting in front of him, is such that it may have appeared mistakenly to Gostling as ‘holding a book’; his halberd however remains unexplained if he is to be identified as the Confessor.” Bernard Rackham, The ancient glass of Canterbury Cathedral (London: Lund, Humphries, 1949), 129.

[3] Richard II, who ordered the window, had a great devotion to Edward and is supported by English kings Edward the Confessor and Edmund the Martyr in the famous Wilton Diptych.