St. Catherine Benincasa is one of only four women to be declared a Doctor of the Church (Oct. 4, 1970) for her contribution to the understanding of Christian scripture and for her advancement of theology. That said, there has long been discussion of the extent to which Catherine was educated, even literate, given that, as a woman during the Late Middle Ages, formal paths of learning were unopen to her. Born in 1347 into a well-off working-class family of Siena, she showed even as a child an inclination towards the holy life.

Against her parents’ preference to see her married, she became a Dominican tertiary at the age of eighteen. The remaining years of her life were spent in a great deal of action, tending to the poor and sick of her community as well as travelling to intercede in political disputes, but also lengthy contemplation, with her receiving many visions over her lifetime and the stigmata in 1375. Between this year and her death in 1380, Catherine also undertook to write a plethora of letters to important figures as well as to those closest to her, these being, in a way, her outlet for preaching, since, at least officially, women were not allowed to preach (as they still are not in some Christian denominations). These letters, and also her greatest work, her “libro,” the Dialogo della divina provvidenza, were almost all dictated to scribes, which has led some scholars to question the degree of Catherine’s agency in her output. But the important thing to remember is that this was not an uncommon practice even for men, and we do know that Catherine wrote some letters herself because she tells us this, though these were written in Italian, not the learned Latin of the clerical elite. Catherine, for her part, however, never let anything deter her. She is perhaps most famously known for marching to Avignon to tell Pope Gregory XI to return to Rome, which he did.

But what of Catherine’s continued learning over the years of her ministry—on her own and through those in her circles—and her intellectual contributions? There has been consideration given to her influences in much of the scholarship, but I will focus on one predecessor that has received limited attention. We know that Catherine was inspired by the likewise politically-involved and reformative twelfth-century mystic and Doctor, St. Bernard of Clairvaux (1090-1153), because Catherine quotes Bernard in some of her letters.[i] However, it is difficult to know how exactly she might have been exposed to his works and to which ones precisely. Nonetheless, there are striking parallels between her theological thinking and Bernard’s, which is something that her confessor and later hagiographer, Blessed Raymond of Capua (1330-1399), emphasized by means of a metaphor that Catherine herself invented of God as a tranquil ocean.

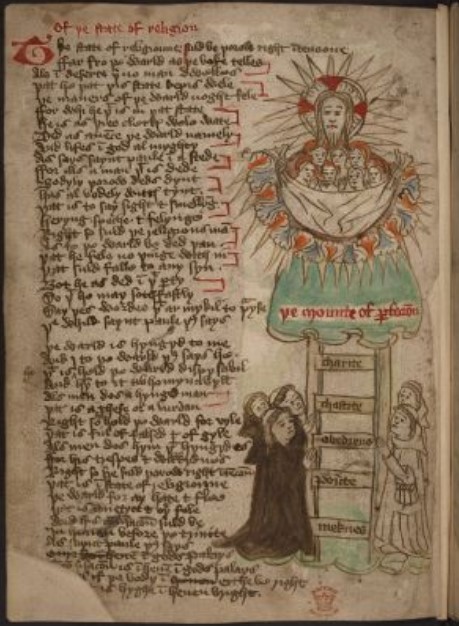

For anyone who has even dabbled in medieval Christian theology and mysticism, it should no doubt have become quickly apparent that a longtime, widespread, major preoccupation is the gradual perfection of the human will in a journey towards God and the hope of beatific vision—you know, the ending of Dante’s Commedia. This ascent of the soul or mind is allegorized using various schemata: ladders or stairs, mountains, trees, the body of Christ, a six-winged seraph, etc. But what is key is that this progression occurs by means of specific steps, stages, or degrees (though these differ slightly from text to text) until the human will—through the soul’s exertion and divine grace working in tandem—becomes so refined, so like unto God’s, that the person’s will and God’s become one, and the individual and God are joined in metaphysical union, the end result being what is called theosis.[ii]

A dramatic transformation occurs, though, between the second and third degrees. The third is attained when a person “loves God not now because of himself but because of God” (41). That is, a person turns from focusing upon themselves to focusing upon something greater, desiring God not for personal gratification, but out of pure love. At this point, caritas is achieved. The fourth degree of love, then, involves a person’s desires becoming superseded by God’s when a person comes to love themselves, others, and all of creation through God because that is God’s will, and in reaching the fourth degree, God’s and a person’s wills become one (29). However, Bernard opines that, “I doubt if he ever attains the fourth degree during this life, that is, if he ever loves only for God’s sake” (41). But if this were to be the case, Bernard says it would occur “when the good and faithful servant is introduced into his Lord’s joy, is inebriated by the richness of God’s dwelling. In some wondrous way he forgets himself and ceasing to belong to himself, he passes entirely into God and adhering to him, he becomes one with him in spirit” (41). When a soul thus arrives at the fourth degree, its final destination, it must turn back to the world through God just as a pilgrim must return to his or her point of origin, but in both cases, the person has been utterly changed through their experiences, acquiring a radically different outlook. However, the attitude that St. Bernard expresses here is that the fourth degree is tricky. Indeed, it requires much of the human person, forgoing one’s will completely and adhering entirely to God.

St. Catherine conceives of a similar progression in her Dialogue, but she makes use of a common devotional image—the body of Christ.[vi] She is also more positive in her hopes for humanity, but her indebtedness to Bernard’s thinking should become abundantly clear, since she too presents a pilgrimage of love, which, as Bernard would say, “advances by fixed degrees, led on by grace” (40). According to Catherine’s schema, the journey begins in a river below a physical bridge, which is Jesus Christ, the ontological and moral Bridge joining Heaven and earth.[vii] Here, a person is trying to forge their way across the swift water into Paradise without consideration for God. But for this reason, they will never succeed (67). Suzanne Noffke, the text’s translator, refers to this stage as “slavish” love because the person is a slave to sin out of love for themselves, and even if they begin to turn to God, the regard remains servile out of fear of punishment (67).[viii] I believe this best fits Bernard’s first degree of love. As Mary Ann Follmar explains more concisely in her commentary, God, with ineffable love, sends the soul gifts, hoping that it will better recognize the true source of its blessings. If this does not work, then God allows the winds of adversity to blow, abetting self-reflection (6-7).[ix] Should all go well, according to the Dialogue, the person will realize that everything they have is from God, and due to this, they will be moved to love with a mercenary love, that is, for the profit they can derive from God (113). The mercenary love enacted at the feet of Christ the Bridge exemplifies Bernard’s second degree (Catherine’s first).

As the person’s affections continue to be ordered through self-knowledge, which inextricably entails knowledge of God, they progress to the side of Jesus through which they enter into Christ’s heart via his side wound.[x] In the arduous climb to Christ’s side, the person becomes a “good and faithful servant,” but as selfishness diminishes further, they become Christ’s friend and pass into his heart (64, 115). Follmar clarifies that, “The opening in the heart signifies intimacy of affection and confidence,” which can only exist between close friends. When someone loves like a friend, they do so without respect for themselves; the person now “loves virtue and every good solely for love of God” (45). This is why they can now experience Christ’s secret, “the manifestation of divine love,” symbolized by the blood poured forth from Christ’s heart upon the cross (46). By reaching the stage where the will of the person has dissipated and is being replaced with God’s, the heart of Christ becomes the person’s own heart. This, I think, is Bernard’s third degree but Catherine’s second.

By way of the heart, the pilgrim then travels to Christ’s mouth. Here, the love has become more than just friendship; now it is also filial. In this last stage, in the words of God to Catherine, the person “loves me for myself, because I am supreme Goodness and deserve to be loved, and she loves herself and her neighbors because of me, to offer glory and praise to my name” (141). The destination of the mouth signifies for Catherine the third and fourth stages of the soul, which seem to represent Bernard’s fourth degree. The distinction Catherine makes is that embracing the world through God and learning to love God in one’s neighbor and self (third) leads to an even more perfect union with God (fourth). Perfect love is achieved in the heart of Christ, but “(most) perfect love,” as Thomas McDermott dubs it, is attained at the third step, which necessarily leads to the greatest union with God that can be accomplished (183-193).[xi] The ultimate end of the journey is to come to the gate on the other side of the Bridge that leads into Paradise, but the threshold may not be crossed while alive. Nevertheless, Catherine, functioning as God’s mouthpiece, tells us that,

For once souls have risen up in eager longing, they run in virtue along the bridge […] and arrive at the gate with their spirits lifted up to me. When they have crossed over [the bridge] and are inebriated with the blood and aflame with the fire of love, they taste in me the eternal Godhead, and I am to them a peaceful sea with which the soul becomes so united that her spirit knows no movement but in me. Though she is mortal, she tastes the reward of the immortal (147-148, my emphasis).

And if the still living pilgrim then turns back to the world through God, she or he can live out Bernard’s fourth degree.

McDermott notes that, “the peaceful sea is […] an image of the soul’s destiny, that of ultimate union with God,” and he is certainly correct (199). But we need to examine this metaphor a bit more closely because it is one that Catherine, as well as Raymond of Capua, rely upon a great deal. And while Catherine’s use of Christ’s body as an allegorical roadmap, of sorts, is helpful, particularly with regard to eliciting an affective response, it also remains abstract from the standpoint of human experience. How can a person, in the flesh, truly conceive of something like the fourth degree of love, conceive of being so united to God that one’s entire existence—one’s reality—is mediated through God? In short, how can we conceive of theosis?

Hannah Zdansky, Ph.D.

University of Notre Dame

[i] One example is in a letter to the Abbess of Santa Marta in Siena. See p. 52 of vol. 1 of The Letters of Catherine of Siena. 3 vols. Trans. Suzanne Noffke. Tempe: Arizona Center for Medieval and Renaissance Studies, 2000. Kenelm Foster notes that some forty such citations have been identified in the Letters. See p. 312 of “St. Catherine’s Teaching on Christ.” Life of the Spirit 16 (1962): 310-323.

[ii] It must be said, though, that Western theologians are often a bit more skeptical of the possibility of theosis than Eastern Christian thinkers, an example of which pessimism we can see in St. Bernard’s work in what follows.

[iii] More information as well as the entire digitized manuscript can be found here: http://www.bl.uk/manuscripts/FullDisplay.aspx?ref=Add_MS_37049. For an excellent study, see Jessica Brantley’s Reading in the Wilderness: Private Devotion and Public Performance in Late Medieval England. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2007.

[iv] For this translation, see On Loving God. Trans. Emero Stiegman. Kalamazoo, MI: Cistercian Publications, Inc., 1995. For an edition of the text, see Liber de diligendo Deo. Sancti Bernardi opera. vol. 3. Ed. J. Leclercq and H. M. Rochais. Rome: Editiones Cistercienses, 1963. 119-154.

[v] Bernard’s understanding of charity and cupidity is very much reliant upon St. Augustine of Hippo’s (354-430). See especially Augustine’s De doctrina christiana (c. 396-427), specifically Bk. 3, Ch. 10, § 16, which is on p. 88 of the following translation: On Christian Doctrine. Trans. D. W. Robertson, Jr. Upper Saddle River, NJ: Prentice Hall, 1997. For an edition, see De doctrina christiana. Ed. J. Martin. Corpus Christianorum: Series Latina. vol. 32. Turnhout, Belgium: Brepols, 1962. 1-167.

[vi] It is quite possible that Catherine was also inspired to use this image through St. Bernard’s third and fourth sermons on the Song of Songs. See On the Song of Songs I. Trans. Kilian Walsh. Spencer, MA: Cistercian Publications, 1971.

[vii] The translation used throughout is the following: The Dialogue. Trans. Suzanne Noffke. Mahwah, NJ: Paulist Press, Inc., 1980. For an edition, see Il Dialogo della Divina Provvidenza ovvero Libro della Divina Dottrina. Ed. Giuliana Cavallini. Rome: Edizioni Cateriniane, 1968.

[viii] See Noffke’s book Catherine of Siena: Vision through a Distant Eye. Collegeville, MN: The Liturgical Press, 1996.

[ix] See Follmar’s The Steps of Love in The Dialogue of St. Catherine of Siena. Petersham, MA: St. Bede’s Publications, 1987.

[x] Heather Webb mentions that St. Bernard of Clairvaux was one of the first to state definitively that the spear which pierced Christ’s side reached all the way to his heart (805). See “Catherine of Siena’s Heart.” Speculum 80 (2005): 802-817.

[xi] See McDermott’s Catherine of Siena: Spiritual Development in Her Life and Teaching. Mahwah, NJ: Paulist Press, Inc., 2008.

Appendix:

| St. Bernard of Clairvaux’s Degrees of Love (De diligendo Deo) |

St. Catherine of Siena’s Degrees of Love (Dialogo della divina provvidenza)

|

| 1. Man loves himself for his own sake: “man first loves himself for himself because he is carnal and sensitive to nothing but himself” (40).

|

0. The River of Sin – Slavish Love: “But those who do not keep to this way travel below through the river […]. And since there is no restraining the water, no one can cross through it without drowning. Such are the pleasures and conditions of the world. Those whose love and desire are not grounded on the rock but are set without order on created persons and things apart from me […] run on just as they do” (67).

“Open your mind’s eye and look at those who drown by their own choice and see how they have fallen by their sins. […] they have become servants and slaves of sin. I made them trees of love through the life of grace […]. But they have become trees of death, because they are dead. Do you know where this tree of death is rooted? In the height of pride, which is nourished by their sensual selfishness” (73). “You know that every evil is grounded in selfish love of oneself” (103).

|

| 2. Man loves God for his own benefit: “when he sees he cannot subsist by himself, he begins to seek for God by faith and to love him as necessary to himself. So in the second degree of love, man loves God for man’s sake and not for God’s sake” (40).

|

1. The Feet of Jesus – Mercenary Love: “There are others who become faithful servants. They serve me with love rather than that slavish fear which serves only for fear of punishment. But their love is imperfect, for they serve me for their own profit or for the delight and pleasure they find in me” (113).

“They love their neighbors with the same love with which they love me—for their own profit” (114).

|

| 3. Man loves God for God’s sake: “When man tastes how sweet God is, he passes to the third degree of love in which man loves God not now because of himself but because of God” (41).

|

2. The Wounded Side of Jesus – Love of Friendship: “If you love me the way a servant loves a master, I as your master will give you what you have earned, but I will not show myself to you, for secrets are shared only with a friend who has become one with oneself. Still, servants can grow because of their virtue and the love they bear their master, even to becoming his very dear friend. So it is with these souls. As long as their love remains mercenary, I do not show myself to them. But they can, with contempt for their imperfection and with love of virtue, use hatred to dig out the root of their spiritual selfishness. They can sit in judgment on themselves so that motives of slavish fear and mercenary love do not cross their hearts without being corrected in the light of most holy faith. If they act in this way, it will please me much that for this they will come to the love of friendship. And then I will show myself to them, just as my Truth said: ‘Those who love me will be one with me and I with them, and I will show myself to them and we will make our dwelling place together.’ This is how it is with very dear friends. Their loving affection makes them two bodies with one soul, because love transforms one into what one loves” (115-116).

|

| 4. Man loves himself for the sake of God: “Happy the man who has attained the fourth degree of love, he no longer even loves himself except for God” (29).

“man remains a long time in this [third] degree, and I doubt if he ever attains the fourth degree during this life, that is, if he ever loves only for God’s sake” (41). “No doubt, this happens when the good and faithful servant is introduced into his Lord’s joy, is inebriated by the richness of God’s dwelling. In some wondrous way he forgets himself and ceasing to belong to himself, he passes entirely into God and adhering to him, he becomes one with him in spirit” (41).

|

3. The Mouth of Jesus – Filial Love: “Now this is how the soul acts who has in truth reached the third stair. This is the sign that she has reached it: Her selfish will died when she tasted my loving charity, and this is why she found her spiritual peace and quiet in the mouth. […] She has let go of and drowned her own will, and when that will is dead, there is peace and quiet” (141).

“She brings forth virtue for her neighbors without pain” (141). “she loves me for myself, because I am supreme Goodness and deserve to be loved, and she loves herself and her neighbors because of me, to offer glory and praise to my name” (141). “After she has come to perfect, free love, she lets go of herself and comes out […]. And this brings her to the fourth stage. That is, after the third stage, the stage of perfection in which she both tastes and gives birth to charity in the person of her neighbor, she is graced with a final stage of perfect union with me. These two stages are linked together, for one is never found without the other any more than charity for me can exist without charity for one’s neighbors or the latter without charity for me. The one cannot be separated from the other. Even so, neither of these two stages can exist without the other” (137).

|