Important Update 7/26/18: The Medieval Institute recently merged the Medieval Undergraduate Research website with this one. All posts from the old site have been transferred here, and the undergraduate content can now be found under the "Undergrad Wednesdays" category. The rest of the information in this post remains accurate and up-to-date.

The Medieval Institute recently launched a new website, Medieval Undergraduate Research, to provide a new community platform for undergraduates studying any area of the Middle Ages. Pedagogically, one of its purposes is to help instructors introduce a new kind of writing assignment in the classroom: the blog post. The recent rise of the digital humanities (DH) has placed particular pressure on medievalists to pursue new scholarly pathways, not only in their own scholarship, but also in the classroom as well. One simple way to increase students’ DH experience is to give them writing assignments based on digital genres. Translating foundational humanities skills–critical thinking, reading, and writing–into newer online platforms, prepares students for a job market that increasingly expects them to be able to communicate effectively in digital mediums.

On this site, posts, carefully revised and edited with help from instructors and myself, the site’s Webmaster, become mini-publications that students can add to their resumes as evidence of their ability to write professionally for a wide audience. Faculty can also use the blog post to encourage students to think about the course material they are learning in an alternative format, not with the intention of replacing the traditional academic essay, but rather as a supplement to it. In fact, many of the standard elements of a conventional assignment could be incorporated into these posts as in the sample assignment provided below. However, students should pay careful attention to audience as the platform encourages students to write “with a different voice and tone than they might use in a traditional essay” and to “explore the multimedia possibilities offered by” the genre.[1] Certain assignments, crafted with an eye towards interlinking and online research, could even focus on developing students’ digital literacy, finding, reading, and evaluating the quality of their online sources.

Contributions to this online forum can address any topic under the large umbrella of medieval studies, leaving the possibilities for assignment topics wide open. For example, a series of posts currently published under the course category “Chaucer’s Biggest Rivals” respond to a prompt written by Kathryn Kerby-Fulton, worth quoting in full:

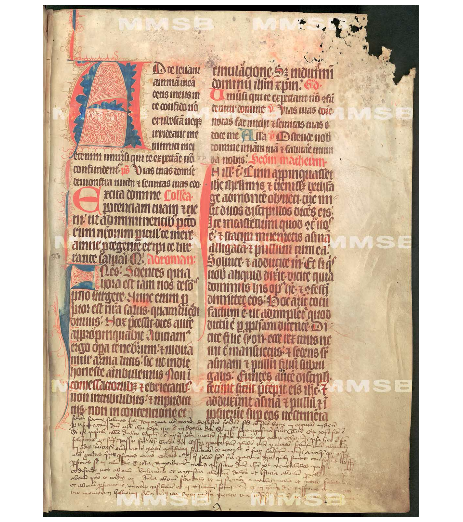

Translation Critique Project for Blog: You can write this blog post either on Pearl or Gawain. There are two parts to this: you will translate a passage of your choice and then comment on the various stylistic devices used by the poet in one of the passages given (e.g. word play, metre, rhyme, stanza structure, imagery). Then you will write a critique of Marie Boroff’s translation (she is considered the best American poetic translator of Middle English). A copy of Boroff’s translations can be purchased inexpensively and one will also be placed on Reserve in the Library; however, her Gawain can also be found in any edition of the Norton Anthology of English Literature. You may wish to look at Boroff’s introduction to her text, where she gives the rationale for her approach. You will want to consider the problems of literary style, accuracy, faithfulness to the medieval poet’s text, and the demands of modern English in your analysis, and you should have no fewer than five examples to illustrate your views. (The Middle English Dictionary and the Oxford English Dictionary are good resources for this type of research as well). The length of this assignment is about 1000 words, so not very long, and we are going to post the best of them online on the ND Medieval Institute’s blog website (Medieval Undergraduate Research), with the help of Dr. Nicole Eddy [the site’s former Webmaster]. And we will put the appropriate image from the Pearl or Gawain manuscript with your post, or perhaps other appropriate images. See: http://blogs.nd.edu/manuscript-studies/undergraduate-research/.

Many of the students tasked with these critiques found innovative ways to connect the material to modern culture in order to adapt their more traditional analyses to this newer genre and to address a wide audience. Examples include Karen Neis’ “An Ugly, Bad Witch” and Elizabeth Kennedy’s “Visceral Moments in Sir Gawain and the Green Knight.”

Some reflections on a manuscript reproduction project completed for a “History of the Book” course at St. Mary’s College across the street are currently joining those translation critiques. These posts, written under the guidance of Sarah Noonan, reflect on the process of manuscript production from the materials (parchment, ink, etc.) to the artistic decisions that go into designing the mise-en-page. Next semester, I will require students in my Canterbury Tales course to write blog posts that close read a short passage in lieu of one of the shorter close reading essays I typically assign. Historians, theologians, and philosophers will likely approach the blog assignment differently, and we welcome disciplinary diversity. We hope to gain wide interdisciplinary coverage that represents the full breadth of Notre Dame’s medieval curriculum.

Instructors using this site as the basis for course assignments should feel free to experiment with a range of traditional and creative prompts. We are also open to accepting work performed for extra credit, so long as the submissions undergo revision based on feedback from an instructor or TA. Individual students are invited to send us individual submissions based on successful work they performed for their classes, such as a major research project, or an analytical essay, revised to match the length and tone of a blog entry.

Moreover, in the coming months, we plan to roll out a supplementary classroom visit program for which I, or one of my regular contributors, will give quest lectures. Our presentations will consist of a twenty-minute talk about how to set up and write a successful blog post in WordPress. This program will provide an additional resource for faculty who want some extra support implementing their technology-based assignments.

We are, of course, far from the first ones to suggest blog posts as course assignments (see what others have said, here, here, and here). However, as opposed to some of the more informal models in common use (weekly reading responses, daily prompts, etc.), all of which serve valuable purposes, the posts for this site are meant to be more formal and involved. As a centralized hub for undergraduate bloggers at Notre Dame, these carefully revised and polished contributions are meant to function more like mini, peer-reviewed publications. With this goal in mind, we encourage faculty and undergraduates to participate in this project and are eager to work with you at any stage of the process.

Sample Assignments:

Update 4/27/18: Here is a sample assignment that aims to improve students’ proficiency in digital genres.

Update 5/4/18: Here is an extra credit assignment also in use for the undergraduate site.

Karrie Fuller, Ph.D.

University of Notre Dame/St. Mary’s College

[1] Claire Battershill and Shawna Ross, Using Digital Humanities in the Classroom: A Practical Introduction for Teachers, Lecturers, and Students (London: Bloomsbury Publishing, 2017).

A few additional resources for DH teaching at the undergraduate level:

Hacking the Academy, May 21-28, 2010 (http://hackingtheacademy.org). (There’s also a book version of this project published by the University of Michigan Press, 2013.)

Brett, Hirsch, ed., Digital Humanities Pedagogy: Practices, Principles, and Politics (Cambridge: Open Book Publishers, 2012).