For this school year’s exciting inaugural post, Maidie Hilmo shares her request for a scientific analysis of the Pearl-Gawain manuscript (British Library, MS Cotton Nero A.x), containing the unique copy of the Middle English poems: Pearl, Cleanness, Patience, and Sir Gawain and the Green Knight. It shows the kind of questions that help gain access to the viewing of original manuscripts and can result in a technological investigation of specific details. Bringing together science and art history, Hilmo has uncovered evidence that “the scribe was also the draftsperson of the underdrawings. It appears that the painted layers of the miniatures were added by one or more colorists, while the large flourished initials beginning the text of the poems were executed by someone with a different pigment not used in the miniatures.” The results of this request to the British Library—comprising the detailed report on the pigments by Dr. Paul Garside and a set of enhanced images by Dr. Christina Duffy, the Imaging Scientist — will become available on the Cotton Nero A.x Project website and, selectively, in publications by Hilmo, including: “Did the Scribe Draw the Miniatures in British Library, MS Cotton Nero A.x (The Pearl-Gawain Manuscript)?,” forthcoming in the Journal of the Early Book Society; and “Re-conceptualizing the Poems of the Pearl-Gawain Manuscript,” forthcoming in Manuscript Studies. To learn more, check out her special project here on our site.

The Art of Imprecise, Imperfect Interpretation: Using the Manuscript Annotations of Piers Plowman as Evidence for the History of Reading

In grade school, I was never one to resist the advice of a teacher. So, when told that successful study habits included taking notes, underlining, and starring right in the book itself, that is precisely what I did. Those teachers were right, of course, and I find myself often repeating the same advice to my own students despite their frequent resistance to marring the pristine pages of their soon to be resold copies of Beowulf and Sir Gawain and the Green Knight. What I did not know in grade school, however, was that writing in my books meant participating in an ancient tradition of responding to and even interpreting texts, and that one day I would write an entire dissertation about how medieval readers read by studying the evidence left behind by the medieval and early modern readers of a famously unstable text called Piers Plowman by William Langland.

The truth is that people have pretty much always written in their books and, sometimes, books belonging to others as well—rubricating, annotating, bracketing, scribbling, doodling, and more. Whether those readers responded in sparse intervals, limiting their voice on the page to vague marks, or, in contrast, wrote intensely, vociferously inscribing their presence irrevocably onto the page and into the text itself, these voices often remain the best extant evidence available for scholars attempting to understand the reception history of an author whose earliest readers have long since passed.

One example of a vocal, reform-minded reader can be found in an early modern household manuscript copied by Sir Adrian Fortescue, a distant relative of Anne Boleyn executed by Henry VIII for some unknown act of treason.[1] His manuscript, Oxford, Bodleian Library MS Digby 145, contains a personalized, conflated copy of what we now call the A and C versions of Piers Plowman alongside a political treatise written by Adrian’s uncle, John Fortescue, called The Governance of England. Filled with annotations in the hands of at least three readers, this book documents a series of responses made over time by Adrian, his wife Anne (who signs her name in Latin!), and the unknown Hand B.[2] The conversations among these readers make this record of reader responses particularly special, but it is Hand B, the subject of this post, that becomes the most reactionary to some of Langland’s biting criticisms of the Church.[3]

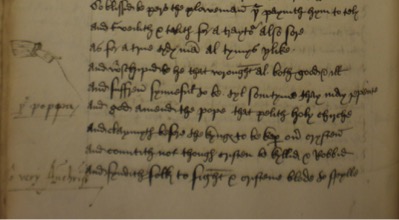

Hand B’s responses become increasingly inflammatory in the poem’s apocalyptic final few Passūs. In fact, he goes so far as to conflate the pope and the Antichrist in two of his annotations. The first annotation appears next to a passage in which Langland criticizes the schismatic pope for his role in the spilling of Christian blood:

þe poppa/ And god amend the pope that pelith holy chirche

And claymyth before the kyng • to be kepar ouer crysten

And countith not though cristen be kyllid & robbid

ô very Antechrist And fyndith folk to fight & cristene blode to spylle.[4]

The annotation, “O Very Antichrist,” transforms Langland’s corrupt pope into the face of the Apocalypse itself, an even more extreme condemnation of immoral papal behavior than Langland’s. This annotation also lays the groundwork for his second conflation in which he identifies Langland’s Antichrist as the pope, writing “puppa [sic]” next to the line, “And a fals fend antecriste ouer al folke reynyd.”[5] Here Hand B reads the Antichrist’s extensive and increasing worldly authority as the same as that belonging to the pope. In both instances, the annotator melds the Antichrist and pope, two separate entities in the poem, into a single figure responsible for an eschatological catastrophe. In some ways, Hand B’s sixteenth-century reactions to this medieval poem make sense amidst a backdrop of increasing religious instability in Henry VIII’s England. Perhaps Hand B saw in the unstable papal seat produced by the Schism a parallel with the splintering of religious power between Rome and Henry leading up to and during the English Reformation.

Beyond these historical inferences, however, what exactly do Hand B’s strong, reform-minded reader responses teach us about the identity of this reader and his interpretation of the poem? In fact, it tells us both a lot and not very much at all. He clearly disagrees with the ecclesiastical corruption that he sees as trickling down from the Church’s highest seat of power, and he reacts strongly, even emotionally, as he inscribes his interpretive voice onto the page. Piers Plowman’s ending evokes a passionate, rather than objective, response from this reader, who adds his own polemical lament to Langland’s verse. This reader provides just one example of the strong personal investment that Langland’s early audiences felt when reading Piers.[6] He also demonstrates how reading and interpreting literature can aid in the formation and circulation of reformist ideas, especially in precarious times.

However, to what end Hand B voices his cry for reform remains unclear. Without knowing his identity, his exact purpose is impossible to discern because he could be either a Catholic hoping for ecclesiastical reform or a Reformation era Protestant. Adrian’s manuscript stayed in his family until Bodley eventually bought it, increasing the likelihood that Hand B was a family member, or at least a close affiliate. Moreover, the Fortescues maintained their Catholic identity throughout the period, but that does not mean that every single member of the family necessarily adopted the exact same religious practices and beliefs. Without word choices that obviously indicate one camp or the other, the greater social implications of Hand B’s readerly perspectives lead to fuzzy conclusions at best. The enigma of whether he desires institutional change or seeks an altogether new institution of faith must by necessity remain unsolved, at least for now. For this reason, scholars must, with care, entertain multiple possibilities, sometimes foregoing exactness and precision when faced with limited evidence for a text’s reception history. Hand B actually teaches us a great deal more about his reading of Piers than many other annotators, but, as is the case with so many historical records of literary readership, his reader responses still require a certain level of imprecise, imperfect, and even incomplete interpretation.[7]

Karrie Fuller, Ph.D.

University of Notre Dame

[1] For Adrian’s biography, see Richard Rex, “Blessed Adrian Fortescue: A Martyr without a Cause?,” Analecta Bollandiana 115 (1997): 307-53.

[2] On Anne Fortescue, see Kathryn Kerby-Fulton, “The Women Readers in Langland’s Earliest Audience: Some Codicological Evidence,” in Learning and Literacy in Medieval England and Abroad, ed. Sarah Rees-Jones (Turnhout: Brepols, 2002), 121-34. On the identification of Hand B, see Thorlac Turville-Petre, “Sir Adrian Fortescue and His Copy of Piers Plowman,” Yearbook of Langland Studies 14 (2000): 29-48.

[3] For my full analysis of these readers’ annotations, see Karrie Fuller, “Langland in the Early Modern Household: Piers Plowman in Oxford, Bodleian Library MS Digby 145, and Its Scribe-Annotator Dialogues,” in New Directions in Medieval Manuscript Studies and Reading Practices: Essays in Honor of Derek Pearsall, eds. Kathryn Kerby-Fulton, John J. Thompson, and Sarah Baechle (Notre Dame: University of Notre Dame Press, 2014), 324-341.

[4] Transcription mine, fol. 121v. The equivalent lines appear in C.XXI.446-449 in A.V.C. Schmidt, Piers Plowman: A Parallel-Text Edition of the A, B, C, and Z Versions, 2nd ed., 2 vols. (Kalamazoo: MI: Medieval Institute Publications, 2011).

[5] Transcription mine, fol. 124r; C.22.64 in Schmidt.

[6] For another example, see Kathryn Kerby-Fulton’s transcription and discussion of the annotations in Bodleian Library MS Douce 104 in Iconography and the Professional Reader: The Politics of Book Production in the Douce “Piers Plowman” (Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 1999).

[7] Examples of more terse annotations, which tend to be more characteristic of B-text manuscripts, can be found in David Benson and Lynne Blanchfield, The Manuscripts of Piers Plowman: The B-Version (Woodbridge: D.S. Brewer, 1997).

Arabic’s Gutenberg: Defining an Era Through the Lens of Print

As thousands of scholars make our pilgrimage to the 52nd annual meeting of the International Congress on Medieval Studies at Western Michigan University in Kalamazoo (known to many affectionately as “the ‘Zoo”) we look forward to the largest gathering of medievalists in North America. Over the course of yesterday (Thursday) through this Sunday, many scholars have and will make contributions to the field that amplify our knowledge and transform our critical understanding of our craft. Since I am privileged with the mic during this auspicious time, I will take this opportunity to address a fundamental question that was raised at one of yesterday’s roundtables: where and when do we locate the “Middle Ages” in a global context? In other words, how can we reevaluate our Eurocentric biases and take into account cultures around the world that don’t fit traditional definitions of medievalism?

The organizers of the Kalamazoo roundtable, the University of Virginia’s DeVan Ard and Justin Greenlee, created a forum to discuss the fraught term “medieval” from various perspectives, including Buddhist art in China (Dorothy Wong), the pre-Islamic Jahiliyyah period (Aman Nadhiri) and the challenges of accurately representing the Middle Ages in the classroom (Christina Normore). The speakers and moderator Zach Stone strove to challenge the artificial boundaries that are often used to constrict the idea of the medieval and to consider, in the words of Nadhiri, “the Middle Ages as a period without the parameters of time.” I offer here an adapted version of my own presentation, which considers the limits of the term “medieval” through the history of the printing press in the Muslim world.

Of all the metrics that various disciplines use to demarcate the end of the Middle Ages—shifts in military tactics, game-changing historical figures, scientific discoveries, etc.—the arrival of Johannes Gutenberg’s printing press in Germany is often seen as the critical moment when Western culture was ‘reborn’ into a new era. Medievalists know well that the effects of this new technology were not as immediate or as clear cut as many outside the field sometimes think, but the ability to disseminate materials more efficiently and more widely led to changes in the economy, literacy, and writing practices rivaled only by the recent progress of the digital age.

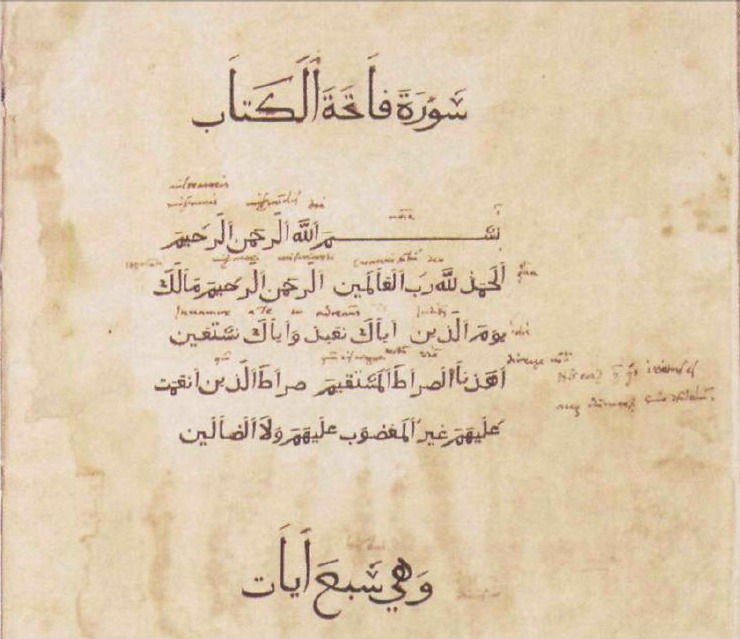

The history of movable type in Arabic provides a point of departure for wider discussions of how to bookend a historical era in the Middle East and North Africa as well as other predominantly Muslim populations. Although the printing press made its way to the Ottoman Empire not long after its introduction in Europe, it was almost immediately forbidden to print in Arabic. Among the various political, social, and theological reasons for this legislation, I argue that the sanctity of the Arabic language itself created resistance to movable type. According to Islam, Arabic is the direct language of God communicated through the angel Gabriel. Many believe that translations of the Qur’an are no longer the holy book, and throughout the early centuries of Islam there were meticulously-enforced rules for the style of writing that could be used for certain texts.

The clumsy attempts of early printers to negotiate the connectors, diacritics, and shape-changing letters of Arabic writing could not hope to represent the word with the accuracy and beauty that it required. Continuing attempts to this day to create functional Arabic fonts and Turkey’s twentieth-century switch from Arabic to Roman script demonstrate that these challenges are still being negotiated. This narrative of technical and literary development, so vastly different from that of Western Europe, offers a lens through which we can consider other intellectual and cultural differences that complicate comparisons between Western Europe and the Arab world.

Erica Machulak

PhD in English

University of Notre Dame

Founder of Hikma Strategies