In grade school, I was never one to resist the advice of a teacher. So, when told that successful study habits included taking notes, underlining, and starring right in the book itself, that is precisely what I did. Those teachers were right, of course, and I find myself often repeating the same advice to my own students despite their frequent resistance to marring the pristine pages of their soon to be resold copies of Beowulf and Sir Gawain and the Green Knight. What I did not know in grade school, however, was that writing in my books meant participating in an ancient tradition of responding to and even interpreting texts, and that one day I would write an entire dissertation about how medieval readers read by studying the evidence left behind by the medieval and early modern readers of a famously unstable text called Piers Plowman by William Langland.

The truth is that people have pretty much always written in their books and, sometimes, books belonging to others as well—rubricating, annotating, bracketing, scribbling, doodling, and more. Whether those readers responded in sparse intervals, limiting their voice on the page to vague marks, or, in contrast, wrote intensely, vociferously inscribing their presence irrevocably onto the page and into the text itself, these voices often remain the best extant evidence available for scholars attempting to understand the reception history of an author whose earliest readers have long since passed.

One example of a vocal, reform-minded reader can be found in an early modern household manuscript copied by Sir Adrian Fortescue, a distant relative of Anne Boleyn executed by Henry VIII for some unknown act of treason.[1] His manuscript, Oxford, Bodleian Library MS Digby 145, contains a personalized, conflated copy of what we now call the A and C versions of Piers Plowman alongside a political treatise written by Adrian’s uncle, John Fortescue, called The Governance of England. Filled with annotations in the hands of at least three readers, this book documents a series of responses made over time by Adrian, his wife Anne (who signs her name in Latin!), and the unknown Hand B.[2] The conversations among these readers make this record of reader responses particularly special, but it is Hand B, the subject of this post, that becomes the most reactionary to some of Langland’s biting criticisms of the Church.[3]

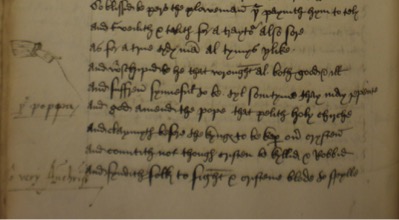

Hand B’s responses become increasingly inflammatory in the poem’s apocalyptic final few Passūs. In fact, he goes so far as to conflate the pope and the Antichrist in two of his annotations. The first annotation appears next to a passage in which Langland criticizes the schismatic pope for his role in the spilling of Christian blood:

þe poppa/ And god amend the pope that pelith holy chirche

And claymyth before the kyng • to be kepar ouer crysten

And countith not though cristen be kyllid & robbid

ô very Antechrist And fyndith folk to fight & cristene blode to spylle.[4]

The annotation, “O Very Antichrist,” transforms Langland’s corrupt pope into the face of the Apocalypse itself, an even more extreme condemnation of immoral papal behavior than Langland’s. This annotation also lays the groundwork for his second conflation in which he identifies Langland’s Antichrist as the pope, writing “puppa [sic]” next to the line, “And a fals fend antecriste ouer al folke reynyd.”[5] Here Hand B reads the Antichrist’s extensive and increasing worldly authority as the same as that belonging to the pope. In both instances, the annotator melds the Antichrist and pope, two separate entities in the poem, into a single figure responsible for an eschatological catastrophe. In some ways, Hand B’s sixteenth-century reactions to this medieval poem make sense amidst a backdrop of increasing religious instability in Henry VIII’s England. Perhaps Hand B saw in the unstable papal seat produced by the Schism a parallel with the splintering of religious power between Rome and Henry leading up to and during the English Reformation.

Beyond these historical inferences, however, what exactly do Hand B’s strong, reform-minded reader responses teach us about the identity of this reader and his interpretation of the poem? In fact, it tells us both a lot and not very much at all. He clearly disagrees with the ecclesiastical corruption that he sees as trickling down from the Church’s highest seat of power, and he reacts strongly, even emotionally, as he inscribes his interpretive voice onto the page. Piers Plowman’s ending evokes a passionate, rather than objective, response from this reader, who adds his own polemical lament to Langland’s verse. This reader provides just one example of the strong personal investment that Langland’s early audiences felt when reading Piers.[6] He also demonstrates how reading and interpreting literature can aid in the formation and circulation of reformist ideas, especially in precarious times.

However, to what end Hand B voices his cry for reform remains unclear. Without knowing his identity, his exact purpose is impossible to discern because he could be either a Catholic hoping for ecclesiastical reform or a Reformation era Protestant. Adrian’s manuscript stayed in his family until Bodley eventually bought it, increasing the likelihood that Hand B was a family member, or at least a close affiliate. Moreover, the Fortescues maintained their Catholic identity throughout the period, but that does not mean that every single member of the family necessarily adopted the exact same religious practices and beliefs. Without word choices that obviously indicate one camp or the other, the greater social implications of Hand B’s readerly perspectives lead to fuzzy conclusions at best. The enigma of whether he desires institutional change or seeks an altogether new institution of faith must by necessity remain unsolved, at least for now. For this reason, scholars must, with care, entertain multiple possibilities, sometimes foregoing exactness and precision when faced with limited evidence for a text’s reception history. Hand B actually teaches us a great deal more about his reading of Piers than many other annotators, but, as is the case with so many historical records of literary readership, his reader responses still require a certain level of imprecise, imperfect, and even incomplete interpretation.[7]

Karrie Fuller, Ph.D.

University of Notre Dame

[1] For Adrian’s biography, see Richard Rex, “Blessed Adrian Fortescue: A Martyr without a Cause?,” Analecta Bollandiana 115 (1997): 307-53.

[2] On Anne Fortescue, see Kathryn Kerby-Fulton, “The Women Readers in Langland’s Earliest Audience: Some Codicological Evidence,” in Learning and Literacy in Medieval England and Abroad, ed. Sarah Rees-Jones (Turnhout: Brepols, 2002), 121-34. On the identification of Hand B, see Thorlac Turville-Petre, “Sir Adrian Fortescue and His Copy of Piers Plowman,” Yearbook of Langland Studies 14 (2000): 29-48.

[3] For my full analysis of these readers’ annotations, see Karrie Fuller, “Langland in the Early Modern Household: Piers Plowman in Oxford, Bodleian Library MS Digby 145, and Its Scribe-Annotator Dialogues,” in New Directions in Medieval Manuscript Studies and Reading Practices: Essays in Honor of Derek Pearsall, eds. Kathryn Kerby-Fulton, John J. Thompson, and Sarah Baechle (Notre Dame: University of Notre Dame Press, 2014), 324-341.

[4] Transcription mine, fol. 121v. The equivalent lines appear in C.XXI.446-449 in A.V.C. Schmidt, Piers Plowman: A Parallel-Text Edition of the A, B, C, and Z Versions, 2nd ed., 2 vols. (Kalamazoo: MI: Medieval Institute Publications, 2011).

[5] Transcription mine, fol. 124r; C.22.64 in Schmidt.

[6] For another example, see Kathryn Kerby-Fulton’s transcription and discussion of the annotations in Bodleian Library MS Douce 104 in Iconography and the Professional Reader: The Politics of Book Production in the Douce “Piers Plowman” (Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 1999).

[7] Examples of more terse annotations, which tend to be more characteristic of B-text manuscripts, can be found in David Benson and Lynne Blanchfield, The Manuscripts of Piers Plowman: The B-Version (Woodbridge: D.S. Brewer, 1997).