Visitors to the Museum of Civilization in Rome can see plaster casts of the entirety of Trajan’s column. Photo by Notafly – Own work, CC BY-SA 3.0, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=4634304

I consider Italian art to be indispensable when teaching Dante. One way to think about the Divine Comedy is as a piece of Late Gothic/Early Renaissance art in poetry. Unfortunately for a classroom teacher, many of the pieces of art that can be most relevant for understanding him ought to be experienced in person because they are as spatial, and they are visual. These works of art do not fit neatly on a screen or piece of paper, and while a video can sometime be helpful in seeing details that are difficult to see in person, it cannot replicate the encompassing nature of the type of art produced in Italy during this time. So, grab a cappuccino (only if it is morning…if it is not, shame on you, espresso is the correct choice!), and plan your Dante-lover trip to Italy. While there are many guides to Italian travel, over the next few posts, I would like to focus here upon some specific pieces of art that Dante lovers ought to pay attention to.

Most visits to Italy begin in Rome, and there are few things more indispensable to reading Dante than an appreciation for his love of the Roman Empire. The first stop is Trajan’s Column in Rome.

Trajan’s Column in Rome, Italy. Photo by Livioandronico2013. Creative Commons.

The emperor Trajan appears twice in the Commedia, once as a carved example of humility in the cornice of the Proud in Purgatorio 10.73-99 and again as one of the six chiefs of Justice in the Circle of Jupiter in Paradiso 20. While reading the Commedia the tendency is to think about Trajan as he is depicted in Voragine’s Golden Legend, as a man saved from hell by the prayers of Gregory the Great:

In the time that Trajan the emperor reigned, and on a time as he went toward a battle out of Rome, it happed that in his way as he should ride, a woman, a widow, came to him weeping and said I pray thee, sire, that thou avenge the death of one my son which innocently and without cause hath been slain. The emperor answered: If I come again from the battle whole and sound then I shall do justice for the death of thy son. Then said the widow: Sire, and if thou die in the battle who shall then avenge his death? And the emperor said: He that shall come after me. And the widow said: Is it not better that thou do to me justice and have the merit thereof of God than another have it for thee? Then had Trajan pity and descended from his horse and did justice in avenging the death of her son. On a time S. Gregory went by the market of Rome which is called the market of Trajan, and then he remembered of the justice and other good deeds of Trajan, and how he had been piteous and debonair, and was much sorrowful that he had been a paynim, and he turned to the church of S. Peter wailing for the horror of the miscreance of Trajan. Then answered a voice from God saying: I have now heard thy prayer, and have spared Trajan from the pain perpetual. By this, as some say, the pain perpetual due to Trajan as a miscreant was some deal taken away, but for all that was not he quit from the prison of hell, for the soul may well be in hell and feel there no pain by the mercy of God.

The visitor to Trajan’s column, which stands in the forum (or market) of Trajan, may have a slightly different perspective. In Roman Art, Donald Strong points out that this column “sets out…to provide an epic version of the [Dacian] wars, with the Roman army under its great leader in the role of hero” (151). In other words, this column shows viewers what Trajan thought was important about his life, the wars he fought and the battles he won.

This monument to the glories of Trajan’s empire does not include the act of kindness remembered by Gregory when he visits the marketplace. To find an artistic engraving of these events of eternal importance, one has to look to the epic poetry of Dante himself:

At that I turned my face

And, looking beyond Mary, saw,

On the same side as he prompted me,

Another story set into the rock.

I went past Virgil and drew near so that my eyes might better take it in.

There, carved into the marble…

Depicted there was the glorious act

Of the Roman prince whose worth

Urged Gregory on to his great victory—

I speak of the emperor Trajan,

With the poor widow at his bridle, weeping,

Revealed in her state of grief

The soil all trampled by the thronging knights.

Above, the eagles fixed in gold

Seemed to flutter in the wind.

In their midst, one could almost hear the plea

of that unhappy creature: ‘My lord, avenge

My murdered son for me. It is for him I grieve,’

And his answer: ‘Wait till I return,’

And she: ‘My lord,’ like one whose grief is urgent,

‘and if you don’t return?’ and his answer:

‘He who will take my place will do it,’

And she: ‘What use to you is another’s goodness

If you are unmindful of your own?’

And he then: ‘Now take comfort, for I must discharge

My debt to you before I go to war.

Justice wills it and compassion bids me stay.’

He in whose sight nothing can be new

Wrought this speech made visible,

New to us because it is not found on the earth. (Purgatorio X.49-96; transl. Hollander)

Now, consider this: one of the iconic features of epic poetry is a figure of description known as ekphrasis, whereby a poet describes a work of art, like a painting or a statuary, in a way that competes with physical craftsman and shows that poetry is capable of doing more than a physical craft. For example, the shield of Achilles is described by Homer so that it has features that would be impossible in real life. (Think Harry Potter paintings.) Ekphrasis was one way that epic poets demonstrated that their craft had superior capabilities to that of other craftsmen.

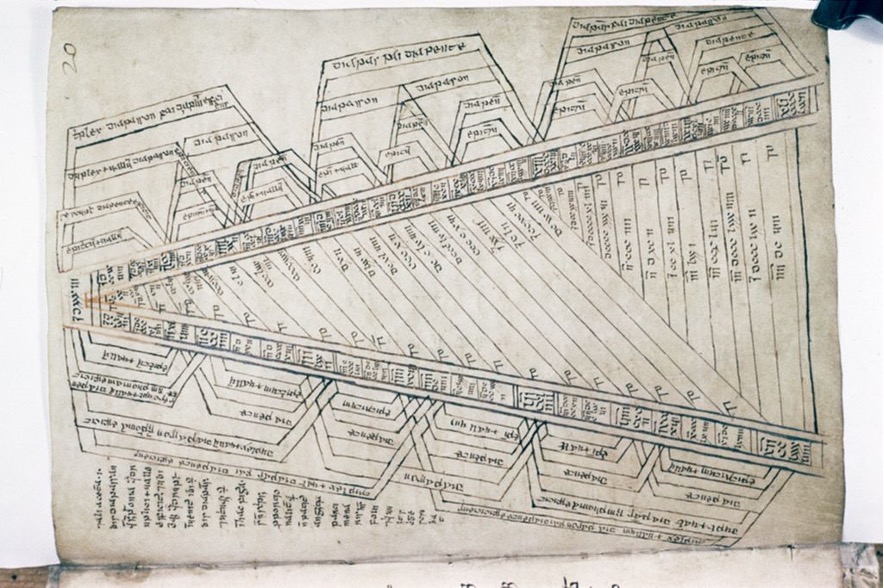

MS Holkam, Misc. 48, p.75, Bodleian Library University of Oxford. https://digital.bodleian.ox.ac.uk/objects/10974934-30a5-4495-857e-255760e5c5ff/surfaces/ef18134f-8c01-4509-89e5-3f82de5ae6f2/

With this perspective in mind, it becomes clearer that Dante’s depictions of Trajan re-write the epic history that Trajan “wrote” for himself in Trajan’s column. In other words, Dante’s poetry competes with a physical piece of art by showing where Trajan’s true glory lay. Dante has imaged for us a “speech made visible” of Trajan’s act of true justice, carved by the divine artisan. Just as Jesus saw the poor woman give a mite to the temple when others marveled at the great riches donated by the wealthy, so Dante imagines the divine artist immortalizing an act that Trajan did not realize would be his most important. As you look at Trajan’s column in Rome, consider what it would take to make a better monument, so realistic that the figures move and make sound, on a subject matter that was higher than Trajan himself could imagine.

Lesley-Anne Dyer Williams is a Professor for Memoria College’s Masters of Arts in Great Books program and graduated with her doctorate from the University of Notre Dame’s Medieval Institute in 2012. She was also the founding director Liberal Arts Guild at LeTourneau University. Her research focuses upon twelfth-century Platonism and poetry, especially Thierry of Chartres and Bernard Silvestris.

Lesley-Anne Dyer Williams

Public Humanities Postdoctoral Fellow

Medieval Institute

University of Notre Dame

Further Reading

Strong, Donald. Roman Art. Yale University Press, 1995.