Have you heard of medieval anchoresses? Most people haven’t. Anchoritism was a fascinating (and odd) phenomenon that happened all across Western Europe and has roots in the early Christian desert hermit tradition. An anchoress was a laywoman who wanted to withdraw from secular life and live instead in solitude, enclosed in a small room attached to an exterior wall of a church or castle, devoting the rest of her earthly life to Christian devotion and such works of service as she could perform from her cell (embroidering liturgical cloths is one example). She would have required a patron or an income from landholdings or other source to support her needs, such as food, water, and clothing. Among women this phenomenon was first documented in England in the twelfth century and became an increasingly popular choice that continued well into the sixteenth. Several handbooks were written for these women, at first in Latin and then in English. Arguably the most famous is the Ancrene Wisse, composed in the early thirteenth century, of which an impressive seventeen manuscripts survive.

This lifestyle choice seems very strange to us today. Who among us would choose to confine herself to a one-room cell for the rest of her life? Wouldn’t you get claustrophobic, or addled by cabin fever, or die from lack of exposure to sunlight? Wouldn’t you just get bored? Not to mention the deeper and off-putting mythologies that have grown up about anchoresses: rites of the dead were said over them at enclosure, they were bricked into their cells, they dug their graves in their cell floors with their hands a little bit every day, they never saw anyone, and their cells were always on the north side of the church so they’d suffer more from cold (they were just that penitential).

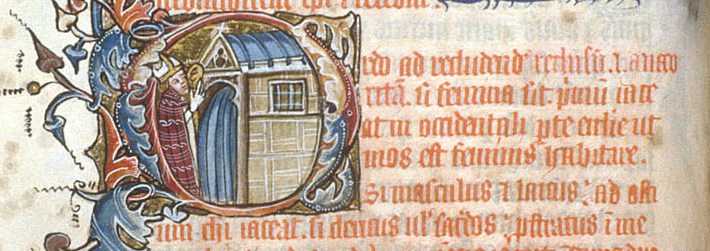

Perhaps the most chilling myth is that anchoresses were all walled up in their cells, like Fortunato in Edgar Allen Poe’s “The Cask of Amontillado.” In fact, while sometimes the exterior door of the cell was bricked in, that was not always the case. Further, the ceremony happened with great solemnity and was a voluntary commitment on the part of the anchoress. Various medieval pontificals, service books for Church bishops, record these rites. The office in the fifteenth-century pontifical of Bishop Lacy calls for the door of the cell to be built up. Others, like the sixteenth-century pontifical of Archbishop Bainbridge directs the anchoress’s door to be firmly shut from the outside. The image above, from an early fifteenth-century Pontifical held at the British Library, accompanies an enclosure rite that begins “Ordo ad recludendum reclusum et anaco/ritam,” or “Ordo [a book containing the rites, sacraments, and other liturgical offices of the Church] for enclosure of a recluse and anchorite.” The bishop makes the sign of the cross above an anchoress entering her cell before enclosing her.

As part of the research for my dissertation-in-progress, a study of lay English women’s literacy in the thirteenth century, I’m visiting a number of medieval English churches that hosted anchorholds (or are rumored to have done so) and chronicling it on my blog. Two of the sites still retain their medieval anchorholds, one pictured at the top of the post and the other below. Interestingly, both have exterior doors.

There is, of course, much more to be said about the exterior fabric of these cells and what has changed over the course of five or six hundred years than is room for here. Nonetheless, the evidence demonstrates that anchoresses’ access to the world was a more complex matter than myth would have you believe.

Megan J. Hall, Ph.D. Candidate

Department of English, University of Notre Dame

Sources

The Pontifical of Bishop Lacy: Exeter, Cathedral Library of the Dean and Chapter, MS 3513

The Pontifical of Archbishop Bainbridge: Cambridge, Cambridge University Library, MS F. vi. 1

F. M. Steele, “Ceremony of Enclosing Anchorites,” in Anchoresses of the West (London, 1903), pp. 47-51.

Rotha Mary Clay, The Hermits and Anchorites of England (London, Methuen 1914).