One of the most challenging Old English terms to translate is the enigmatic aglæca, a term that has prompted an extensive amount of ink spilled. Earlier translators tended to gloss the term as “monster,” a definition that applies to the most frequent usage in the corpus. In this vein, J.R. Clark Hall’s Concise Anglo-Saxon Dictionary defines aglæca (m.) as “wretch, monster, demon, fierce enemy” and the related term, aglæc (n.) as “trouble, distress, oppression, misery, grief” (15). Similarly, Bosworth Toller’s Anglo-Saxon Dictionary offers these six definitions for aglæca (n.): “A miserable being, wretch, miscreant, monster, fierce combatant.” These foundational sources substantiate the many translations that render the term as “monster,” albeit with neutral exceptions such as “fierce combatant” when referring to positive figures and heroes.

Recent critical editions, however, reflect a different trajectory. These editions shift to something more akin to “fierce combatant” than “monster.” For example, in Beowulf: A Critical Edition, edited by Bruce Mitchell and Fred Robinson, the term appears as “fierce combatant, adversary” (241). Similarly, Klaeber’s Beowulf: Fourth Edition, edited by R.D. Fulk, Robert Bjork and John Niles, glosses aglæca (m.) as “one inspiring awe or misery, formidable one, afflicter, assailant, adversary, combatant” (347). Lastly, the University of Toronto’s Dictionary of Old English [DOE] adheres to this trend, in glossing the term as “awesome opponent, ferocious fighter.” None of these more recent editions include “monster” or “wretch” as definitions for the term, nor do any related terms such as “demon” or “miscreant” that carry an unequivocally pejorative sense.

The new convention attempts to solve a longstanding problem associated with Beowulf. In that poem, references to both monsters and heroes provoked a blatant inconsistency, which glossed negatively in referencing the monsters and positively in referencing the heroes. The proposed solution to this inconsistency was located in a reference to Bede as the aglæca lareow “aglæca teacher, master, preacher.” Given Bede’s renowned for learned equanimity, it was reasoned that the term could not denote a pejorative meaning. Accordingly, the now conventional glosses, “awesome opponent, ferocious fighter” applied equally to demonic monsters (Satan in Juliana and Grendel in Beowulf), heroic warriors (Beowulf and Sigemund in Beowulf), missionary saints ( St. Andrew in Andreas) and the venerable scholar (Bede in the prose text, Byrhtferth’s Manual).

The Old English poem Beowulf contains the majority of uses of aglæca forms in the entire literary Old English corpus. Indeed, 20 of the 34 iterations of aglæca occur in the poem (159, 425, 433, 556, 592, 646, 732, 739, 816, 893, 989, 1000, 1259, 1269, 1512, 2520, 2534, 2557, 2592, 2905), and 11 iterations apply specifically to Grendel (159, 425, 433, 591, 646, 732, 739, 816, 989, 1000, 1269), marking him as the primary aglæca in Old English literature. Outside of Beowulf, the term aglæca features predominantly for Satan and his demonic minions, marking the term as principally associated with devils. Including Grendel, references to explicitly demonic monsters as aglæca occur in 24 of its 34 occurrences, suggesting either a demonic or monstrous association and underscoring that aglæca often carries a pejorative sense. Moreover, if we apply a critical lens to some of the heroes in Beowulf who are labeled aglæca, namely Heremod, Sigemund and Beowulf himself, as Griffith, Koberl, Orchard, Gwara and others have done, the pejorative could then extend to the heroic figures in the poem.

In sum, the term is used primarily throughout the corpus to refer to monsters or demons—and above all Satan and Grendel. But, it is also notably used to describe heroes in Beowulf, Saint Andrew in the Old English Andreas, and most bewilderingly of all, to describe Bede. Alex Nicholls points this out in his transformative article highlighting this outlier reference to a renown and highly respected church father as an aglæca, which rightly prompted careful study aimed at reconsidering the Old English term’s semantics based primarily on the unusual context in which the term appears in this text, “Bede ‘Awe-inspiring’ Not ‘Monstrous’: Some Problems with Old English Aglæca.” And, while we commend this thoughtful reconsideration, we would argue that in fact the article may ultimately have had too large an impact on the semantics of the term, especially defined neutrally as “awesome opponent” as it appears in Toronto’s Dictionary of Old English. As in with other terms, here seems one where two definitions could help, one for the predominant usage of the term, and one that also accommodates the single prose use of the term for Bede.

One glaring problem with this solution is that the modern sense of “awesome” is primarily—almost universally—positive, which is diametrically opposed to what the extant lexicographical evidence suggests with respect to the semantics of aglæca. Instead, the sense is principally and overwhelmingly pejorative. Thus, we would argue that “awesome opponent” as a modern English translation does not bear out across the corpus. We contend rather that “awful opponent” would better capture the general sense of the term in the vast majority of contexts in which aglæca appears. But, even this isn’t quite right.

Unfortunately, the DOE’s second definition provides an equally unsatisfactory solution in opting for “ferocious fighter” as a translation for aglæca. As Mark Griffith observes, if the term merely signifies an “formidable opponent,” or something similar, “then it is very curious that it is not used of other figures in the poetry who could be appropriately so labeled” (35). The term aglæca is a noun traditionally understood to be derived from a compound that combines a form of the ege, which Bosworth-Toller defines as “fear, terror, dread, awe” with a form of the verb lacan, which Bosworth-Toller defines as “to swing, to wave about, to play, to fight.” Thus, defining aglæca as “ferocious fighter” erases the wondrous and terrifying quality [ege] and strips the term of one of its formative elements.

Nichols offers “awe-inspiring” thereby maintaining the “fear” sense in the term, the semantics would apply to both monstrous figures (like Satan and Grendel) as well as marvelous/wonderous heroes. It is ege or “awe” in the sublime and wondrous sense of the term. We would argue that “monster” is actually not so bad a translation as the concept of “wonder” and “monster” in the medieval period were interwoven in the early medieval literature. Indeed, Charlton T. Lewis and Charles Short’s A Latin Dictionary, generally regarded considered the best resource for medieval Latin, offers two definitions of monstrum:

1.) a divine omen indicating misfortune, an evil omen, portent

2.) a monster, monstrosity (whether a living being or an inanimate thing)

This wondrous, portentous quality—this uncanniness—is consistently applicable to aglæca —from Satan to Bede. There is of course also the combative aspect of the compound, which seems in every case to correspond to not only an intruder but something akin to a fearsome marauder—an uncanny invader.

This brings us back to Bede—the one lone positive iteration that seems not to carry a pejorative sense—which occurs in a text from later than most iterations (11th century) and is also the only iteration of the term in prose writing. While this use of the term for Bede is puzzling, though far from inexplicable, it seems overkill to disregard the pejorative sense that applies to the term in 33 of 34 iterations and interpret the semantics of the term as neutral because of a single outlier, especially one removed from the poetic and to a lesser extent the historical context in which the majority of uses of the term appear. Moreover, if we consider the possibility of including “wondrous intruder” as a definition for aglæca, it better applies to Bede’s supernatural visitation. While we are in no way advocating for a return to rendering aglæca as “monster” in modern English translations of Beowulf, nor do we consider “awesome opponent” or “ferocious fighter” suitable definitions for aglæca, because the former definition suggests disingenuously probative semantics and the latter disregards the sense of ege “awe” contained in the term. If the term aglæca is understood as a “wondrous intruder” or an “uncanny invader” it applies more neatly to all the Old English contexts in which the term appears. But even these translations lack satisfaction as they largely elide (or at least diminish) the fearful, pejorative sense carried by at least the major of the contexts in which the term appears. This is in part because the word “wonder” and its related forms in modern English are regarded much more positively, whereas an Old English wundor could certainly be marvelous in either a neutral or miraculous sense, but could equally be regarded as monstrous.

Richard Fahey & Chris Vinsonhaler

Medieval Institute

University of Notre Dame & CUNY University

Selected Bibliography & Further Reading

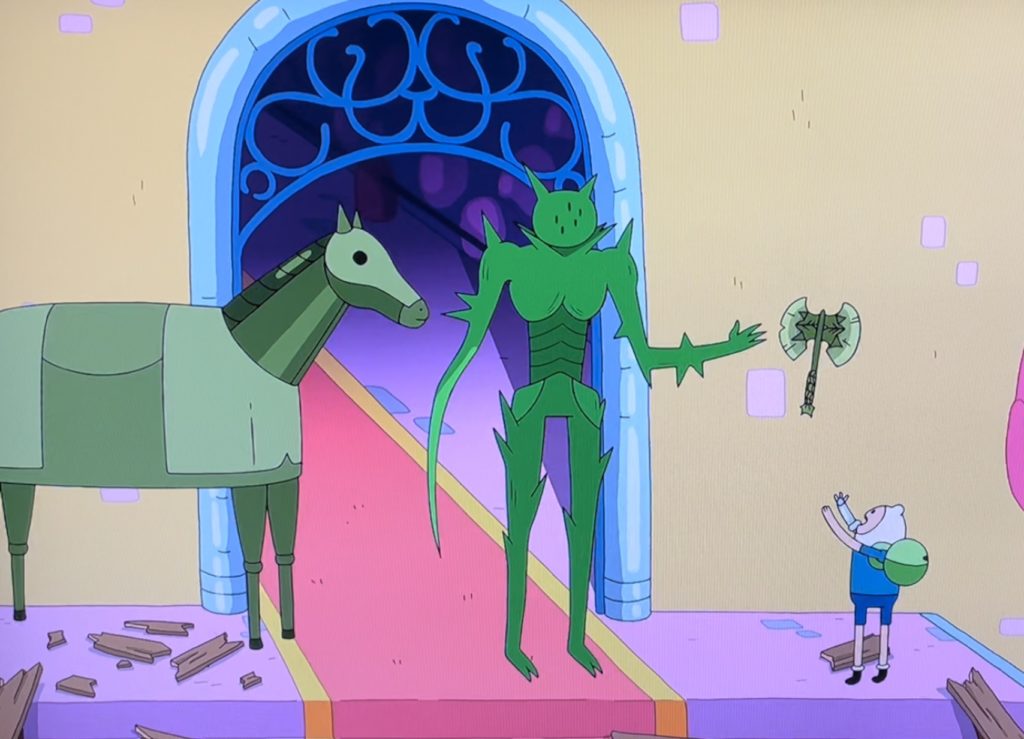

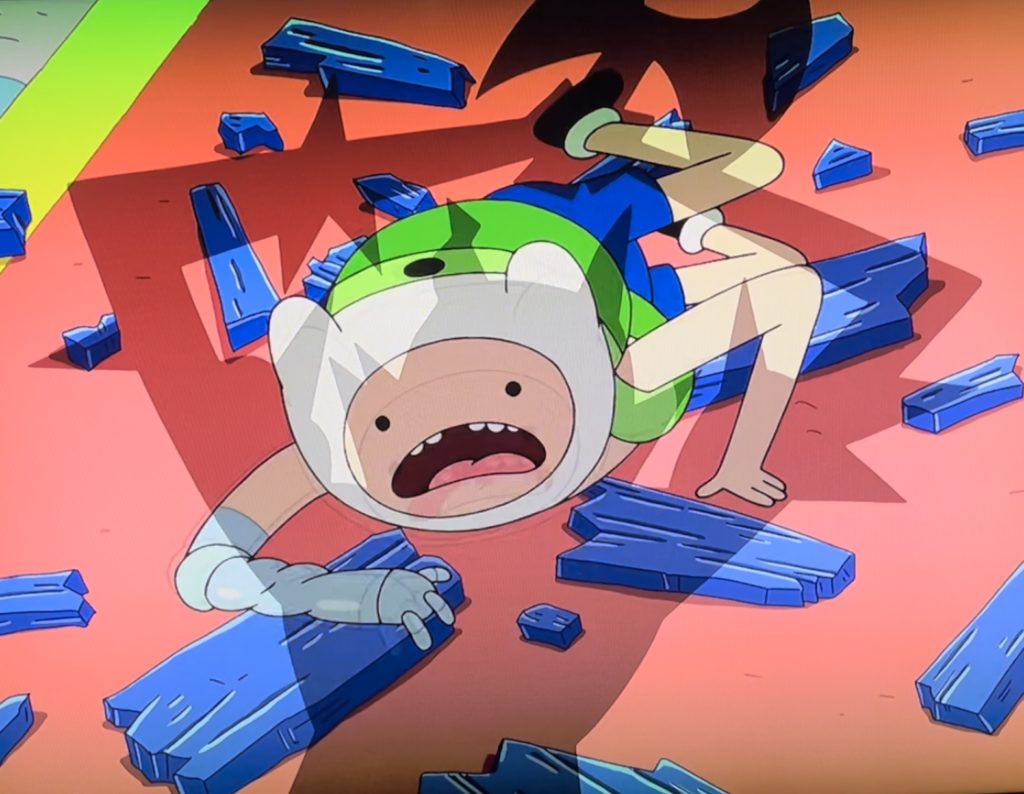

Fahey, Richard. “Grendel’s Shapeshifting: From Shadow Monster to Human Warrior.” Medieval Studies Research Blog. Medieval Institute: University of Notre Dame (October 27, 2021).

—. “Enigmatic Design & Psychomachic Monstrosity in Beowulf.” Dissertation: University of Notre Dame (2019).

—. “The Lay of Sigemund.” Medieval Studies Research Blog. Medieval Institute: University of Notre Dame (March 22, 2019).

Griffith, Mark. “Some Difficulties in Beowulf, Lines 874-902: Sigemund Reconsidered.” Anglo-Saxon England 24 (1995): 11-41.

Gwara, Scott. Heroic Identity in the World of Beowulf. Leiden, Netherlands: Brill, 2009.

Köberl, Johann. The Indeterminacy of Beowulf. Lanham, MD: University of America Press, 2002.

Nicholls, Alex. “Bede ‘Awe-inspiring’ Not ‘Monstrous’: Some Problems with Old English Aglæca.” Notes and Queries 38.2 (1991): 147-48.

O’Brien O’Keeffe, Katherine. “Beowulf, Lines 702b-836: Transformations and the Limits of the Human.” Texas Studies in Literature and Language 23.4 (1981): 484-94.

Orchard, Andy. Pride and Prodigies: Studies in the Monsters of the Beowulf-Manuscript. Toronto, ON: University of Toronto Press, 1995.

Schulman, Jana K. “Monstrous Introductions: Ellengæst and Aglæcwif.” In Beowulf at Kalamazoo: Essays on Translation and Performance, 69-92. Kalamazoo, MI: Medieval Institute Publications, 2012.

Vinsonhaler, N. Chris. “The HearmscaÞa and the Handshake: Desire and Disruption in the Grendel Episode.” Comitatus: A Journal of Medieval and Renaissance Studies 47 (2016): 1-36.