In continuing my discussion of cryptic information encoded in runes in the Exeter Book Riddles, in which I argue runic literacy functions as a form of esotericism, I wish to expand the conversation by considering the variety of specialized information contained in a group of Old English riddles featured in the collection (Riddles 7-10). I will refer to these as bird-riddles, by which I mean specifically a group of potentially related riddles in the Exeter Book whose accepted solutions are birds. As this description promises, these riddles feature bird imagery and their riddle-speaker is generally a specific bird of some kind. Patrick Murphy has suggested that bird-riddle imagery may act also as a mode of obfuscation in the Exeter Book Riddles, and he contends that in Riddle 57, letters (litterae), or rune-staves (runstafas or bocstafas), are probably the best solution to this verbal puzzle, which Murphy argues likens flocking black birds to letters forming words on vellum or parchment.

The Exeter Book bird-riddles display a range of references, as they encode learned and folkloric knowledge. Most of the bird-riddles contain specific references to an encyclopedic source of medieval knowledge, Isidore of Seville’s Etymologiae, which endeavors to define, interpret and explicate the Latin words contained therein. While Isidore reports his share of false etymologies, his text is widely considered authoritative with regard to the study of Latin terminology during the Middle Ages. Mercedes Salvador-Bello has demonstrated the profound extent to which information and even organization principles outlined in Isidore’s Etymologiae serve as models for zoological Exeter Book Riddles, though not all of the clues in the Old English riddles are shared by this Latin source (in fact, many times the information contained diverges significantly).

Most of the Exeter Book bird-riddles rely on some form of esotericism and references to specific information. I now will briefly consider three of bird-riddles, which encode specialized knowledge and may be associated with Isidore’s Etymologiae in addition to other classical sources, especially Pliny’s Historia naturalis. Furthermore, numerous riddle collections from early medieval England likewise feature bird-riddles, such as Anglo-Latin enigmata composed by authors such as Aldhelm (Enigmata 14, 22, 26, 31, 35, 42, 47, 57, 63-64) and Eusebius (Enigmata 38, 56-60), a Latin literary tradition interwoven with its vernacular counterpart as Dieter Bitterli and other scholars have shown. Old English bird-riddles that seem to allude to Isidore’s Etymologiae XII, include Riddle 7 (solved swon “swan”), Riddle 8 (solve nihtegale “nightingale”), Riddle 9 (solved geac “cuckoo”) and Riddle 24 (solved higora “magpie”). Today’s discussion will center on Riddles 7-10 from the Exeter Book collection.

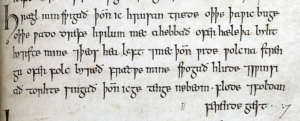

| Riddle 7 |

| Hrægl min swigað, þonne ic hrusan trede, oþþe þa wic buge, oþþe wado drefe. Hwilum mec ahebbað ofer hæleþa byht hyrste mine, ond þeos hea lyft, ond mec þonne wide wolcna strengu ofer folc byreð. Frætwe mine swogað hlude ond swinsiað, torhte singað, þonne ic getenge ne beom flode ond foldan, ferende gæst. |

| “My dress is mute, when I tread the ground, or occupy my abode or stir the water. Sometimes my garments and this high wind heave me over the city of heroes, and then the strength of the skies bears me far and wide over the people. My adornments then resound loudly, and ring, and sing brightly, when I am not hanging on sea or land, a traveling spirit.” |

The muted attire of the swan (swon) does not feature in the Etymologiae, and its feathers do not sing when in flight . The swan (cygnus) does produce cantus dulcissimos “the sweetest songs” according to Isidore’s Etymologiae XII.vii.1, and the etymological relationship between the swan and its song is repeatedly stressed, namely how cycnus autem a canendo est appellatus, eo quod carminis dulcedinem modulatis vocibus fundit “moreover, the swan is named for singing because it unleashes the sweetness of song with modulated voice” (Etymologiae XII.vii.18). However, this reference and emphasis on the creature’s beautiful vocalization probably does not explain the full extent of learned references in this riddle. The image of the swan’s melodious feathers is found also in the Old English Phoenix (131-39), and both J. D. A. Ogilvy and Craig Williamson consider these possible references to an epistle that describes the sweet and harmonious song of the swan’s wings by Gregorius Naziansenus to Celeusius, a Latin translation of which they believe may have circulated in early medieval England.

As with other bird-riddles, Exeter Book Riddle 7 refers to the bird’s hyrst “garment” (4). The word hyrst seems to be a repeated clue encoded in numerous bird-riddles, though the term itself operates somewhat more ambiguously, rather than making direct mention of feathers or otherwise explicit references to their riddle-subjects’ physicality.

Like Riddle 7, the speaker of Exeter Book Riddle 8 is clearly also some kind of songbird. Emphasis on this aspect exceeds even its treatment in the previous riddle.

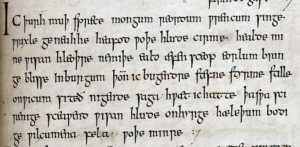

| Riddle 8 |

| Ic þurh muþ sprece mongum reordum, wrencum singe, wrixle geneahhe heafodwoþe, hlude cirme, healde mine wisan, hleoþre ne miþe, eald æfensceop, eorlum bringe blisse in burgum, þonne ic bugendre stefne styrme; stille on wicum sittað nigende. Saga hwæt ic hatte, þe swa scirenige sceawendwisan hlude onhyrge, hæleþum bodige wilcumena fela woþe minre. |

| “Through my mouth, I speak with many voices, I sing in variations. Frequently, I mix head-sounds. I cry out aloud, I keep my counsel. I do not conceal my voice. The old evening-poet brings bliss to men in cities, when I storm the citizens with my voice. They sit still, listening in their homes. Say what I am called, who so clearly proclaims loudly a feasting song, announces to heroes, many welcome things with my voice.” |

As with the swan, Isidore includes the nightingale in his catalogue of birds, stating that luscinia avis inde nomen sumpsit, quia cantu suo significare solet diei surgentis exortum “the nightingale is a bird that took its name because it is accustomed to mark the onset of the coming day by its song” Etymologiae XII.vii.37. This stress on the nightingale’s singing in the wee hours of the morning—in the dark calling the day—is alluded to in the characterization of the nightingale (nihtegale) as æfensceop “evening poet” (5), though surely calling the bird uhtsceop “daybreak-poet” would have been closer to Isidore’s suggestion that the nightingale (luscinia) summons the lux “light” specifically with its call, Latin terms the medieval lexicographer contends may be etymologically related.

On the other hand, considering niht “night” is referenced in the Old English word for this bird (nihtegale), emphasis on æfen “evening” would serve as a better vernacular clue. Salvador-Bello points out that the many voices of the nightingale (luscinia) may suggest knowledge of a passage from Pliny’s Historia naturalis (X.xliii.82-85), while Williamson posits this information may also come from Ambrose’ Hexameron (V.xxiv.85), as both texts emphasize the varied tones featured in the nightingale’s song in their discussion of this melodious songbird.

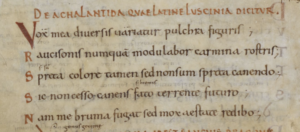

Of course, more obvious and likely is the reference in Aldhelm’s Enigma 22, solved acalantida (another Latin word for nightingale) reference directly after luscinia by Isidore (Etymologiae XII.vii.37). Aldhelm’s riddle explains how vox mea diversis variatur pulcra figuris,/ raucisonis numquam modulabor carmina rostris “my beautiful voice is varied by diverse styles, never will I sing songs with raucous beak” (1-2), which accounts for emphasis on how ic þurh muþ sprece mongum reordum,/ wrencum singe “through my mouth, I speak with many voices, I sing in variations” (1-2) in Exeter Book Riddle 8. Aldhelm’s Enigma 22 also states that non sum spreta canendo/ sic non cesso canens fato terrente futuro “I am not to be spurned for my singing, thus I do not stop singing even if doomed to a terrifying fate” (3-4), which corresponds to the description of reverence for the riddle-speaker’s song in the Old English bird-riddle.

Moreover, Riddle 8 describes the nightingale (nihtegale) as æfensceop “an evening poet” (5), employing stock imagery in order to misdirect the solver, and allowing the riddle to expound on the nocturnal songs of the nightingale under the guise of storytelling and heroic tales. That the æfensceop “evening poet” is said to scirenige sceawendwisan/ hlude onhyrge, hæleþum bodige “clearly proclaim a feasting song, declare loudly, announce to heroes” (9-10) further extends the equivocation between bird and poet. Riddle 8 thereby uses formulaic language and heroic diction to obfuscate the riddle’s solution, again referencing hæleþa (10) as previously in Riddle 7 (3). Moreover, the notion that people revere the nightingale’s song and sit in attention—as warriors listening intently to heroic poetry—is corroborated by Alcuin’s elegy devoted to this songbird, titled De luscinia.

Although the term hyrst “garment” from Riddle 7 does not appear in Exeter Book Riddle 9, the theme of clothing and adornments nevertheless pervades this riddle.

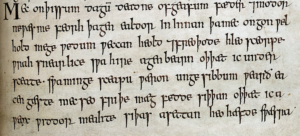

| Riddle 9 |

| Mec on þissum dagum deadne ofgeafun fæder ond modor; ne wæs me feorh þa gen, ealdor in innan. þa mec an ongon, welhold mege, wedum þeccan, heold ond freoþode, hleosceorpe wrah swa arlice swa hire agen bearn, oþþæt ic under sceate, swa min gesceapu wæron, ungesibbum wearð eacen gæste. Mec seo friþe mæg fedde siþþan, oþþæt ic aweox, widdor meahte siþas asettan. Heo hæfde swæsra þy læs suna ond dohtra, þy heo swa dyde. |

| “In these days, father and mother gave me up for dead. There was no life yet in me, no spirit within. Then one well-meaning kinsman began to wake me in my garment, held and sheltered me, wrapped me in protective-gear so tenderly as her own child, until I, under her cover, became enlarged in spirit among my non-siblings as was my destiny. Afterward, that protective kinswoman fed me until I grew up, and could make wider journeys. She had fewer of her own sons and daughters because she did so.” |

In this riddle, the cuckoo (geac) is described as if it were a shapeshifter, and its famously treacherous behavior is stressed, as much of the paradox is centered on questions of kinship and the evolution of the bird’s experience from its abandonment—to fostering—and finally betrayal of its host family. Most of these details are outlined by Pliny the Elder.

| Pliny, Naturalis Historia X.xi-26-27 |

| 26. inter quae parit in alienis nidis, maxime palumbium, maiore ex parte singula ova, quod nulla alia avis, raro bina. causa pullos subiciendi putatur quod sciat se invisam cunctis avibus; nam minutae quoque infestant. ita non fore tutam generi suo stirpem opinatur, ni fefellerit; quare nullum facit nidum, alioqui trepidum animal. 27. educat ergo subditum adulterato feta nido. ille, avidus ex natura, praeripit cibos reliquis pullis, itaque pinguescit et nitidus in se nutricem convertit. illa gaudet eius specie miraturque sese ipsam, quod talem pepererit; suos comparatione eius damnat ut alienos absumique etiam se inspectante patitur, donec corripiat ipsam quoque, iam volandi potens. nulla tunc avium suavitate carnis comparatur illi. |

| “It always lays its eggs in the nest of another bird, and that of the ring-dove more especially, mostly a single egg, a thing that is the case with no other bird; sometimes however, but very rarely, it is known to lay two. It is supposed, that the reason for its thus substituting its young ones, is the fact that it is aware how greatly it is hated by all the other birds; for even the very smallest of them will attack it. Hence it is, that it thinks its own race will stand no chance of being perpetuated unless it contrives to deceive them, and for this reason builds no nest of its own: and besides this, it is a very timid animal. In the meantime, the female bird, sitting on her nest, is rearing a supposititious and spurious progeny; while the young cuckoo, which is naturally craving and greedy, snatches away all the food from the other young ones, and by so doing grows plump and sleek, and quite gains the affections of his foster-mother; who takes a great pleasure in his fine appearance, and is quite surprised that she has become the mother of so handsome an offspring. In comparison with him, she discards her own young as so many strangers, until at last, when the young cuckoo is now able to take the wing, he finishes by devouring her. For sweetness of the flesh, there is not a bird in existence to be compared to the cuckoo at this season” (translation by John Bostock). |

The parasitic nature of the cuckoo is referenced in Isidore’s Etymologiae, but the nature of their freeloading is quite different, as instead the cuckoo (cuculus) is accused of having milvorum scapulis suscepti propter breves et parvos volatus “taken up with the wings of kites because of its [the cuckoo’s] brief and short flight” (XII.vii.67). Isidore also notes that avium nomina multa a sono vocis constat esse conposita “many names of birds appear to be construed from the sound of their voice” (XII.vii.9), and includes the cuckoo (cuculus) in his list along with the swan (cyngus), but this detail is not mentioned in the Old English riddle.

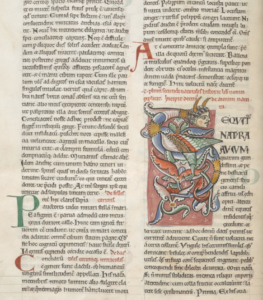

Now for Riddle 10, the final and only bird-riddle in this sequence, whose riddle-subject appears nowhere in Isidore’s Etymologiae.

| Riddle 10 |

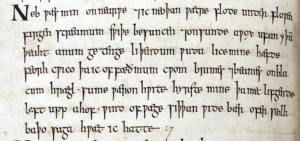

| Neb wæs min on nearwe , ond ic neoþan wætre, flode underflowen, firgenstreamum swiþe besuncen, ond on sunde awox ufan yþum þeaht, anum getenge liþendum wuda lice mine . Hæfde feorh cwico, þa ic of fæðmum cwom brimes ond beames on blacum hrægle. Sume wæron hwite hyrste mine, þa mec lifgende lyft upp ahof, wind of wæge, siþþan wide bær ofer seolhbaþo. Saga hwæt ic hatte. |

| “My beak was in narrowness, and I was beneath the water, I was subsumed by the ocean, I was sunk deep in the briny current. I awoke in my swimming, covered over by waves, near those travelers of wood, with my body. I had a living spirit, when I came from the bosom of sea and tree in black garments. Some of my decorations were white, when the breeze heaved me up, living, the wind from the wave, after that it bore me widely across the seal-bath. Say what I am called.” |

As mentioned, Riddle 10 is unique because—unlike the other subjects of Exeter Book bird-riddles—the barnacle goose (bernaca) is conspicuously absent from the catalogue of birds in Isidore’s Etymologiae. The riddle is rather generic in its description of the bird being on blacum hrægle “in black garments” (7), and wearing white hyrste “decorations” (8). Moreover, the description of how lyft upp ahof “the breeze heaves me up” (9) echoes other bird-riddles. However, the solution can be deduced if one is familiar with Insular folklore surrounding the barnacle goose (bernaca), first attested in this riddle but corroborated by later sources such as Gerald of Wales’ Topographia Hiberniae (c.1188). This legend suggests that the barnacle goose is born by spontaneous generation on trees that grow over water. And, there is an added level of equivocation resulting from a homographic pun on hyrst (8), which could refer either to the masculine noun hyrst “copse, wood” or more likely to the feminine noun hyrst, meaning “ornament, decoration, trapping” and this pun connects the bird’s physical characteristics with its unnatural birth from water and wood. If the solver is familiar with this insular barnacle goose legend, the solution is revealed, but if not it is obscured.

A careful source study of this sequence of Exeter Book bird-riddles (Riddles 7-10) demonstrates how although Isidore’s Etymologiae does discuss three of the four bird-riddles in the group, in many cases the specifics of the Old English riddles reference information in sources a bit more ancient and esoteric, and other sources from classical Latin (such as Pliny’s Historia naturalis) to more contemporary Old English (such as the Exeter Book Phoenix) and Anglo-Latin (such as Aldhelm’s Enigma 22) offer arcane details displayed in the riddles more precisely. This suggests that while Salvador-Bello may have identified an Isidorean orientation, intellectual framework and organizing principle behind the Exeter Book Riddles, Old English riddlers and enigmatists were reaching beyond the Etymologiae and further afield into more obscure territory, especially folklore and esotericism, when creating their verbal puzzles in early medieval England.

Richard Fahey

PhD in English

University of Notre Dame

Editions and Translations:

Aldhelm. Aldhelmi Opera (MGH), edited by Rudolf Ehwald, 211-326. Berolini and Weidmann, 1961.

—. Enigmata. In Variae collectiones aenigmatum Merovingicae aetatis (CCSL 133), edited by Maria De Marco, 359-540. Turnhout, Belgium: Brepols, 1968.

—. Aldhelm: The Poetic Works. Translated by Michael Lapidge and James L. Rosier. Dover, NH: D. S. Brewer, 1985.

Eusebius. Enigmata. In Variae collectiones aenigmatum Merovingicae aetatis (CCSL 133), edited by Maria De Marco, 209-71. Turnhout, Belgium: Brepols, 1968.

Exeter Anthology of Old English Poetry. Edited by Bernard J. Muir. Exeter, UK: University of Exeter Press, 1994.

The Old English Riddles of the Exeter Book. Edited by Craig Williamson. Chapel Hill, NC: University of North Carolina Press, 1977.

Pliny, The Elder. Natural History, with an English Translation. Edited and translated by H. Rackham. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1943.

Tatwine and Eusebius. “The Riddles of Tatwine and Eusebius.” Edited and translated by Mary J. M. Williams. Dissertation: University of Michigan, 1974.

Works Cited and Further Reading:

Bayless, Martha. “Alcuin’s Disputatio Pippini and the Early Medieval Riddle Tradition.” In Humour, History and Politics in Late Antiquity and the Early Middle Ages, edited by Guy Halsall, 157-78. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press, 2001.

Bitterli, Dieter. Say What I Am Called: The Old English Riddles of the Exeter Book and the Anglo-Latin Riddle Tradition. Toronto, ON: University of Toronto Press, 2009.

Dailey, Patricia. “Riddles, Wonder and Responsiveness in Anglo-Saxon England.” In Early Medieval English Literature, edited by Clare A. Lees, 451-72. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press, 2012.

Fahey, Richard. “Reading Runes in the Exeter Book Riddles.” Medieval Studies Research Blog. University of Notre Dame, Medieval Institute. February 17, 2017.

Murphy, Patrick. Unriddling the Exeter Riddles. University Park, PA: Pennsylvania State University Press, 2011.

Ogilvy, Jack D. A. Books Known to the English, 597-1066. Cambridge, MA: Mediaeval Academy of America, 1967.

Orchard, Andy. “Enigma Variations: The Anglo-Saxon Riddle-Tradition.” In Latin Learning and Old English Lore: Studies in Anglo-Saxon Literature for Michael Lapidge, edited by Katherine O’Brien O’Keeffe and Andy Orchard, 284-304. Toronto, ON: University of Toronto Press, 2005.

Salvador-Bello, Mercedes. Isidorean Perceptions of Order: The Exeter Book Riddles and Medieval Latin Enigmata. Morgantown, WV. West Virginia University Press, 2015.

Williamson, Craig. A Feast of Creatures: Anglo-Saxon Riddle-Songs. Philadelphia, PA: University of Pennsylvania Press, 2011.