This Halloween, I’d like to talk about werewolves, one of the classic monsters whose image helps to characterize this—my favorite—holiday.

Werewolves, while sometimes overshadowed by the more frequent and high-profile appearance of other monsters such as vampires and zombies in popular literature, have a mythology that has endured for millennia and still finds a way to haunt our cultural imagination. Unsurprisingly, werewolves feature in Victorian Gothic literature, including works such as Hugues, the Wer-Wolf by Sutherland Menzies (1838), Wagner the Wehr-Wolf (1847) by G. W. M. Reynolds, “The Man-Wolf” (1831) by Leitch Ritchie, “A Story of a Weir-Wolf” (1846) by Catherine Crowe and The Wolf Leader (1857) by Alexandre Dumas.

When werewolves have appeared in more recent popular literature, they often do so in the context of a prescribed, age-old struggle between their kind and vampires. Werewolf-vampire racial animosity is dramatized in the film series Underworld (2003), which injects an unlikely love story into the ancient war between these monstrous groups. This conflict has since become a regular feature of modern vampire films, such as in Van Helsing (2004) and What We Do in the Shadows (2014), and in TV series such as Twilight (2008) and True Blood (2008). Penny Dreadful (2014), a show which delights in Victorian monstrosities, also nods to this tradition when two werewolf characters (Ethan and Kaetenay) are forced to battle a gang of vampires, while Hemlock Grove (2013) alternatively features both a werewolf named Peter and a vampyric upir named Roman who share mutual respect and admiration.

Generally whenever we see werewolves in modern popular literature, it is in this shared context, which is also true of the the TV series Being Human (2011); however, werewolves have (in a few cases) been given center stage. The classic and most obvious examples are the films An American Werewolf in London (1981) and An American Werewolf in Paris (1997).

More recently, in Harry Potter and the of Azkaban (2004), Remus Lupin, who is one of the wizard professors at Hogwarts and also a werewolf, is a main protagonists in the film, despite that vampires feature nowhere in the series and are rarely mentioned even in J. K. Rowling’s novels. For Teen Wolf (2011), a TV series focused on a teenage boy’s struggle with lycanthropy, the absence of vampires is a point of pride. Often werewolves have been gendered male, but the TV series Bitten (2014) challenges this stereotype by centering the plot on a female werewolf protagonist and her struggles within a werewolf patriarchy. Unfortunately, and counterproductively, the series is plagued by a consistent hyper-sexualization of her character in a manner all too familiar from the modern vampire craze. I’d like to believe this inconsistent and contradictory messaging might have contributed to the show’s discontinuation in 2016, but somehow I doubt it.

Today, we will discuss skin-changing and werewolfism in the medieval literary traditions of Northern Europe, primarily as contained in the context of the Old Norse fornaldarsǫgur. We will also consider how lycanthropy in the Old Norse Hrólfs saga kraka and Vǫlsunga saga inform certain instances of skin-changers in modern literature, especially in the fantasy worlds of J. R. R. Tolkien and George R. R. Martin.

Numerous academic blogs have explored the topic of lycanthropy, usually—and unsurprisingly—around this same time of year. In fact, the website Sententiae Antiquae has, in years passed, written a blog series on werewolves in the classical tradition, including blogs on Petronius’ werewolf story from Satyricon (62), Pliny the Elder’s emphasis on clothing and description of werewolf superstitions in his Natural History (8.80-4), and an overview of classical lycanthropy producing a list of sources including, Herodotus’ Histories, Plato’s Republic, Pausanias’ Geography of Greece, anonymous Greek Medical Treatises on the Treatment of Lycanthropy, St. Augustine of Hippo’s City of God, and the 11th century medieval Latin poem, Poemata 9.841, by a monk named Michael Psellus (which is notably influenced by Greek medical treatises). These blogs have tended to focus especially on classical superstitions, such as nakedness being a prerequisite for transformation and the belief that a wolf’s gaze could paralyze humans.

The British Library has also composed a blog on lycanthropy in the context of the influence of classical werewolf mythology on later medieval literature. This blog references classical werewolf stereotypes primarily derived from Pliny’s description of versipelles ‘skin-changers’ (his term for werewolves) in Natural History, and then moves to consider especially Bisclavret, the famous Breton lay by Marie de France, and Gerald of Wales’ description of an Irish folktale concerning lycanthropy in his Topographica Hibernica, both of which present a very positive image of a werewolf, complete with the capacity for human understanding and compassion.

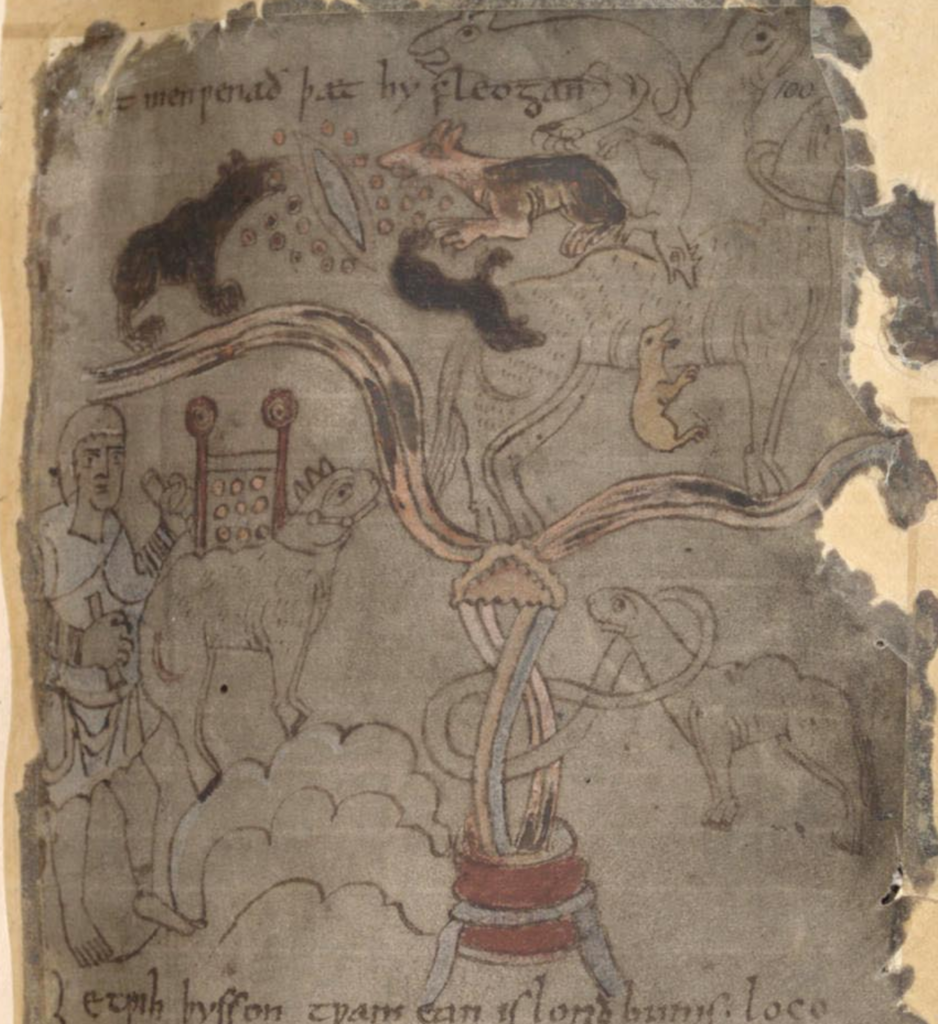

However, as mentioned earlier, werewolves appear also in the vernacular traditions of medieval Scandinavia, and this blog aims to expand the web-conversation surrounding versipelles ‘skin-changers’ in medieval literature to include examples from Old Norse saga prose literature, which contain numerous references to humans transforming into various beasts, usually wolves or bears.

This Old Norse tradition of skin-changers contributes directly to Tolkien’s character of Beorn, the werebear from The Hobbit (1937). Gandalf describes Beorn in chapter VII “Queer Lodgings” when Thorin and his company are traveling through the Misty Mountains:

“He [Beorn] is a skin-changer. He changes his skin: sometimes he is a huge black bear, sometimes he is a great strong black-haired man with huge arms and a great beard. I cannot tell you much more, though that ought to be enough. Some say that he is a bear descended from the great and ancient bears of the mountains that lived there before the giants came. Other say that he is a man descended from the first men who lived before Smaug or the other dragons came into this part of the world, and before the goblins came into the hills out of the North. I cannot say, though I fancy the last is the true tale. He is not the sort of person to ask questions of. At any rate he is under no enchantment but his own.”

Beorn, like his namesake Bjǫrn (a hero from Hrólfs saga kraka), transforms physically from man to bear—though Bjǫrn’s transformations are the product of a curse by his evil stepmother, Queen Hvít, as opposed to Beorn who seems in full control of his metamorphoses in The Hobbit. Jesse Byock’s The Saga of the King Hrolf Kraki reads:

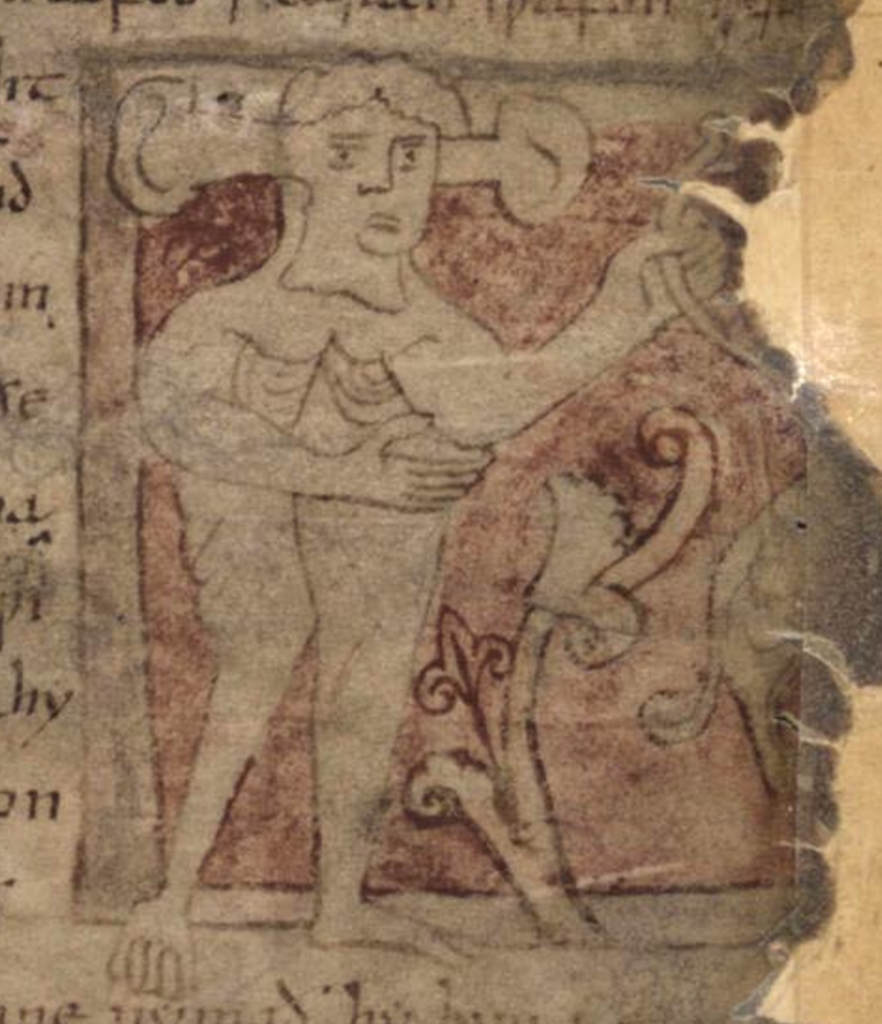

“She [Hvít] then struck him [Bjǫrn] with her wolfskin gloves, telling him to become a cave bear, grim and savage: ‘You will eat no food other than your own father’s livestock and, in feeding yourself, you will kill more than has ever been observed before. You will never be released from the spell, and your awareness of this disgrace will be more dreadful to you than no remembrance at all.’ Then Bjorn disappeared, and no one knew what had become of him…. Next to be told is that the king’s cattle were being killed in large numbers by a grey bear, large and fierce. One evening it happened that Bera, the freeman’s daughter, saw the savage bear. It approached her unthreateningly. She thought she recognized in the bear the eyes of Bjorn, the king’s son, and so she did not run away. The beast then moved away from her, but she followed it all the way until it came to a cave. When she entered the cave, a man was standing there” (37).

This passage describes the power of the queen’s curse to physically transform Bjǫrn, which leads ultimately to his death at the hands of his own father and his warriors. However, it also emphasizes that, while Bjǫrn is dangerous to the livestock, he retains his humanity and at night transforms back into a man.

The character of Bǫðvar Bjarki, son of Bjǫrn (who too shares characteristics and some parallel achievements with Beorn from The Hobbit), also from Hrólfs saga kraka, trances and in doing so is able to inhabit the mind of a bear and control its actions. This is particularly crucial during the saga’s climactic battle between the monstrous army of Hjǫvard and Skuld and the forces of King Hrólf.

The ability to enter into and take over an animal’s consciousness, as a form of shape-shifting through meditation, appears also in George R. R. Martin’s A Song of Ice and Fire (1991)—and corresponding HBO series Game of Thrones (2011)—in the contexts of characters called ‘wargs’ who possess this distinct ability. This group includes a number of those in the Stark family (whose family sigil is appropriately a direwolf). In Martin’s series, characters described as wargs are always from the wintry North, and regularly use their possessed animals to battle their enemies, as in Hrólfs saga kraka.

The Old Norse Vǫlsunga saga, more famous for its dragon and dwarf (namely, Fáfnir and Regin) than its werewolves, does nevertheless have a section in which Sigmundr and Sinfjǫtli specifically wear wolf-pelts in order to transform themselves into wolves and roam the wilderness together in wolf-form. Jesse Byock’s The Saga of the Volsungs reads:

“One time, they went again to the forest to get themselves some riches, and they found a house. Inside it were two sleeping men, with thick gold rings. A spell had been cast upon them: wolfskins hung over them in the house and only every tenth day could they shed the skins. They were the sons of kings. Sigmund and Sinfjotli put the skins on and could not get them off. And the weird power was there as before; they howled like wolves, both understanding the sounds” (44).

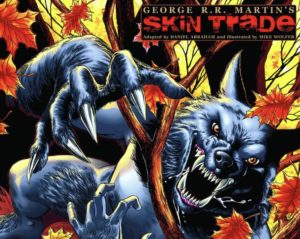

This passage describes the ability to “skin-change” into a wolf by literally wearing a wolf’s skin. This version of ‘skin-changing’ is picked up and adapted in two of Martin’s fictional works: his short story “In the Lost Lands” (1982) and his novella The Skin-Trade (1988).

In Martin’s short story, a character named Boyce travels into the formidable ‘Lost Lands’ to the north, which constitute an endless frozen wilderness, with a witch named Grey Alys (who borrows heavily from mythology of Freya, especially with regard to her cloak of feathers).

I won’t spoil the ending for those who haven’t yet and might be interested in reading this text, except to say that lycanthropy appears initially as a physical transformation, but by the end we learn that wearing the skin of a werewolf can produce the same metamorphosis for those whom the transformation isn’t biological.

Similarly, in his later novella, The Skin-Trade, Martin establishes a world in which both biology and werewolf skin-wearing can result in lycanthropy. Werewolf fans may be happy to learn that The Skin-Trade is currently ‘in development’ by Cinemax under the direction of scriptwriter Kalinda Vazquez, who has written for other TV series such as Prison Break (2005) and Once Upon a Time (2011). However, particularly because there is currently no clear sense as to when Cinemax and Vazquez will have their version of The Skin-Trade ready for the silver screen, it may still be a while before there is a werewolf series to rival HBO’s True Blood or AMC’s The Walking Dead.

Richard Fahey

PhD Candidate

Department of English

University of Notre Dame

Online Resources

Pliny the Elder’s Natural History (8.80-4)

Gerald of Wales’ Topographica Hibernica

Translations

Byock, Jesse. The Saga of King Hrolf Kraki. London, England: Penguin Books, 1998.

Byock, Jesse. The Saga of the Volsungs. London, England: Penguin Books, 1999.