I have a fascination with the strange and obscure, and if I find oddities and curiosities during my travels that intersect with my medieval interests, even better. On a recent trip to Italy, I encountered a creature from both Greek mythology and medieval bestiaries at one of the most wonderfully macabre sites I’ve explored.

While on vacation in Rome this summer, I visited the Capuchin Crypt, an underground mausoleum containing an elaborate arrangement of human bones – lots and lots of bones. No one knows who designed the beautiful and haunting configurations comprised from the bones of approximately 3,700 bodies, presumably those belonging to Capuchin monks who sought refuge from religious persecution in France and perished while in Rome.

Unfortunately, photos are not allowed, and efforts to describe the intricacies and expanse of the design prove rather futile. Skulls and pelvic bones combine to create sculptures reminiscent of butterflies in the arches of doorways. Vertebrae dot and line the ceilings of the chambers like so many fresco tiles. Massive piles of assorted bones have been shaped into seats for carefully posed skeletons. Reviewing his experience, the Marquis de Sade rated the exhibit five stars by modern standards.

But the crypt is a 17th-century construction. It’s the museum that contains the medieval bits, and that’s where I noticed an early print book, dated to the 15th or 16th century, that clearly depicted a cockatrice and that the museum had identified as a harpy.[1] To be fair, the label included a question mark, indicating that the curator was unsure as to what kind of creature was on display.

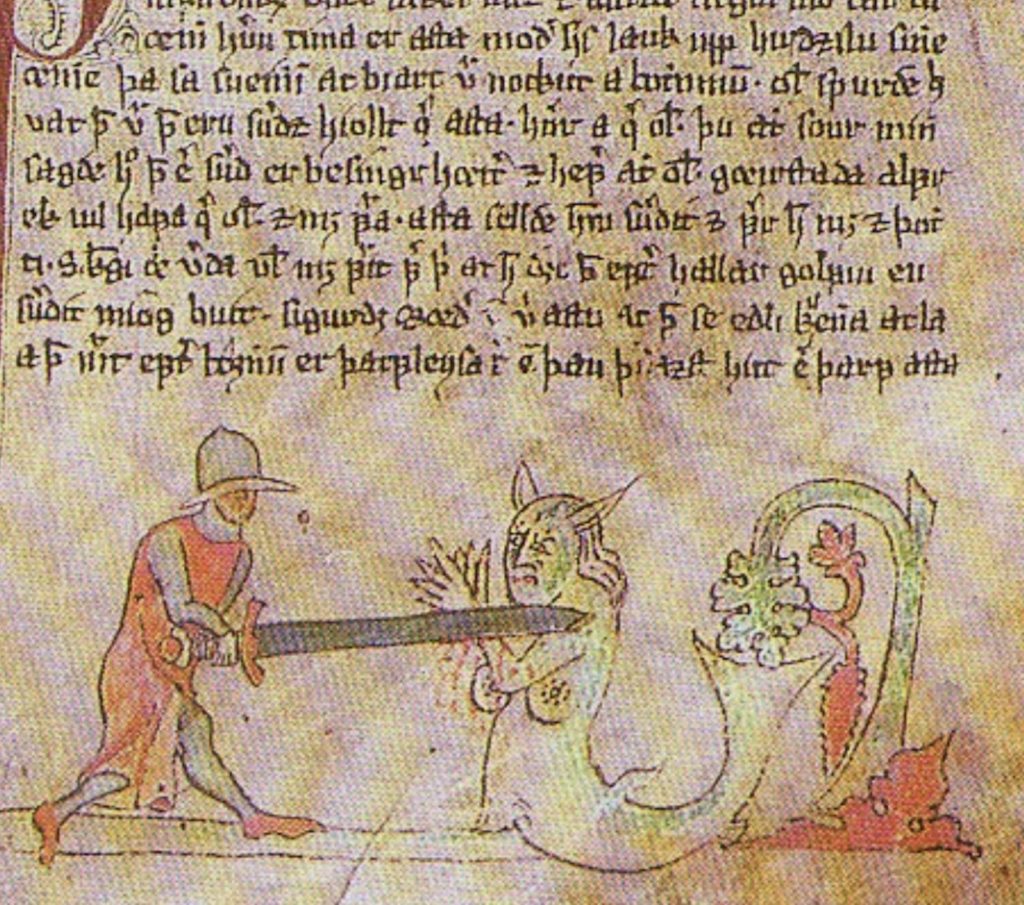

Far less familiar than the harpy, the cockatrice is a legendary creature with a dragon’s body and a rooster’s head. The beast was believed to be hatched from a rooster’s egg incubated by either a serpent or a toad. Its first recorded mention in English appears in a Wycliffite bible dated 1382.[2]

The cockatrice seems to have become synonymous with the basilisk in medieval bestiaries. [3] Most often, basilisks are depicted as a bird, typically a rooster, with a snake’s take. In some illustrations, the basilisk is all snake in terms of physical characteristics, though often with a crest reminiscent of a rooster’s head. The mythologies of the cockatrice and basilisk also share similar elements. As with the basilisk, it is fatal for a person to look the cockatrice in the eyes. Both creatures’ breath can also cause death according to folklore.

A harpy, in contrast to the cockatrice, has a bird’s body with a human head and no serpent components. When I mentioned the mislabeling to the front desk staff, I was told that a historian had recently visited the museum and indicated the reverse but without additional explanation. I assured them that the rooster-headed serpent was—hands down—a cockatrice. Harpies have bird bodies, human heads, and zero snake parts. As imperatively, harpies are depicted as female.

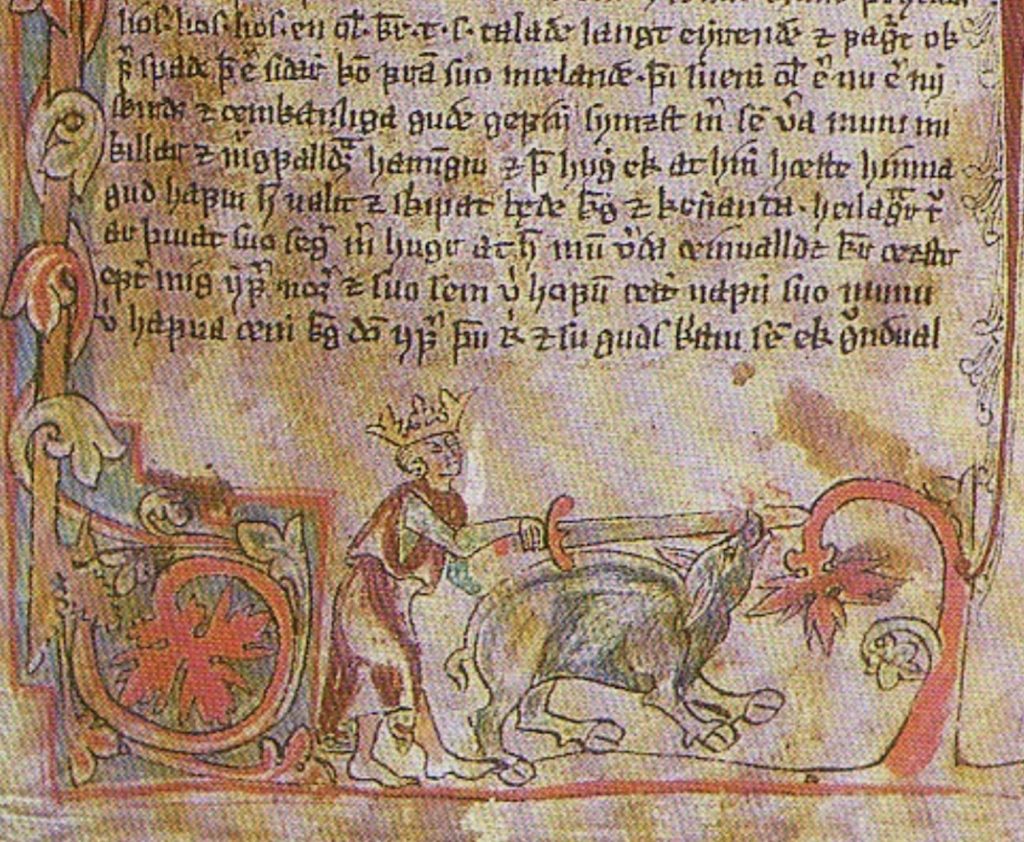

According to Greek mythology, harpyiai were winged female spirits thought to be embodied in sharp gusts of wind, and while certainly fearsome, they were not always so bestial. Known as the “hounds of Zeus,” the female entities were sent from Olympus to snatch people or objects from the earth. Sudden disappearances were, as a result, often attributed to the harpies.

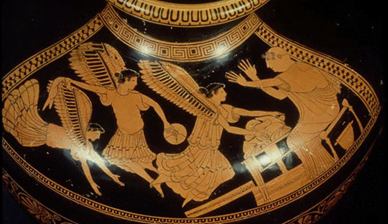

In their earliest representations, harpies appeared as winged women, sometimes with the lower bodies of birds. They were vengeful creatures but not hideous in appearance. Writing between 750 and 650 BC, Hesiod describes harpies as winged maidens with beautiful hair, whom he praises for swiftness in flight that exceeds the speed of storms and birds. Homer, writing roughly around the same time, mentions a female harpy but says nothing derogatory about her looks.

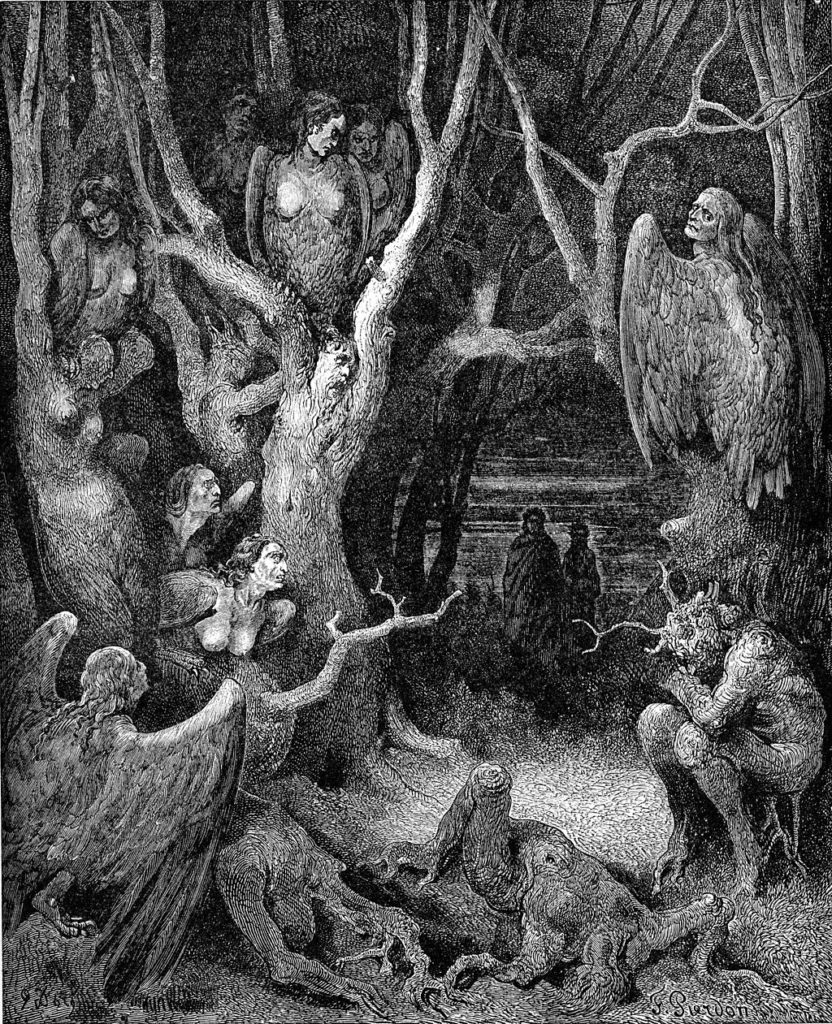

By the end of the classical period, harpies had become monstrous portraits of femininity. They were birds with the heads of maidens, their faces visibly hungry, and had long claws extending from their hands. In the writings of Aeschylus around 500 BC, they are described as disgusting creatures with weeping eyes and foul breath. Virgil, in his Aeneid dated 30-19 BC, refers to them as bird-bodied and female-faced with talons for hands, whose faces reflect insatiable hunger and whose droppings are notably vile. These grotesque portrayals of the harpy—half woman, half monster—are the most well-known from classical mythology.

Interestingly, one mythographer did stick a rooster’s head on the otherwise female body of a harpy. Writing in Rome during the 1st century AD, Hyginus describes harpies as having feathered bodies, wings, and cocks’ heads and the arms, bellies, breasts, and genitals of a human woman.[4] Still, there are no serpent parts here to suggest that a medieval image of a cockatrice might instead be a harpy based on Hyginus’s design.

During the Middle Ages, harpies may not have been so distinctly gendered, at least in their encyclopedic cataloguing. Most representations in medieval bestiaries depict the creatures with bird bodies and female faces, but several manuscript illustrations appear androgynous and some even portray the harpy with a beard. The beard, however, may not be indicative of a male beast but instead emphasize the beastliness of the female creature.

Furthermore, Ovid’s retelling of the Jason story in his Metamorphoses specifically mentions the harpies having the faces of virgin women. Written in the 9th century, Ovid’s collection of myths served as a source text for many medieval writers, including Dante Alighieri and Geoffrey Chaucer, and his treatment of the harpies suggests that their association with female monstrosity continued to resonate soundly during the period.

Turning to the etymology of the term, the first recorded instance of harpy in English actually appears in Chaucer’s Monk’s Tale around 1405.[5] The creatures are not specifically gendered; they are simply mentioned among the monsters defeated by Hercules, at which point the text reads, “He Arpies slow, the crueel bryddes felle” [“He slew the Harpies, the fierce cruel birds”] (2100).[6] Yet one cannot help but see the feminine slippage in the spelling of “bryd,” meaning both “bird” and “bride” in Middle English.[7] Indeed, the term harpy adopts a derogatory connotation in writing by the mid- to late 15th century.[8] The term cockatrice, too, took on a negative meaning specifically with respect to women by the mid-16th century, at which point it referred to a prostitute or a sexually promiscuous woman.[9]

While it’s possible that the harpy may have maintained some gender ambiguity during the medieval period, contemporary etymology and ideology has synonymized the harpy with femaleness but also, importantly, with power. The sheer number of times Hillary Clinton was called a “harpy” during her presidential campaign highlights how a powerful woman was characterized as not only threatening but also monstrous while pursuing a position historically deemed male domain.[10]

Harpies in medieval fantasy films are also perched at the intersection of femaleness and power, glorious in their might regardless of how monstrous their bodies may be. The Last Unicorn, a 1982 animated adaptation of Peter S. Beagle’s 1968 novel, provides a poignant example. Captured by a traveling circus, the titular character finds herself caged across from a harpy, the only authentic creature of legend in the menagerie apart from the unicorn herself.

In a magnificently ominous scene, the audience hears the harpy before they see her. A low growl grows to a raspy screech as the harpy appears on screen. She appears more bird than human, but her grotesque body is blatantly female with three elongated breasts visible beneath her beard and boar’s tusks. A knotted tree limb cracks from the strength of her talons, and her eyes glow red with rage when her captor approaches her cage. Once freed, she kills the old woman who boasted of keeping a harpy captive when no one else could.

Considering the harpy’s history, it seems a shame to mistake her for any other creature from Greek mythology or medieval bestiaries. She has been such a fraught representation of both femininity and monstrosity, but she has also endured as a symbol of female ferocity. Even as her beauty eroded over the centuries, her power has not waned, and her macabre femininity has never ceased to inspire fear.

Emily McLemore, Ph.D.

Alumni Contributor, Department of English

[1] Photos are prohibited in the museum, so I have no physical record of the image. I attempted to contact the Capuchin Museum regarding the object on display to acquire additional information, including the date and location of production, but received no response.

[2] “Cockatrice,” n. Oxford English Dictionary.

[3] “Basilisk,” The Medieval Bestiary.

[4] Fabulae from The Myths of Hyginus, translated and edited by Mary Grant.

[5] “Harpy,” n., def. 1, Oxford English Dictionary.

[6] Geoffrey Chaucer, The Monk’s Tale, The Canterbury Tales, Harvard’s Geoffrey Chaucer Website.

[7] “Brid” and “Brid(e,” n., Middle English Compendium, University of Michigan.

[8] “Harpy,” n., def. 2, Oxford English Dictionary.

[9] “Cockatrice,” n. def. 3, Oxford English Dictionary.

[10] For more on Greek mythology, female monstrosity, and contemporary resonance, I recommend Jess Zimmern’s Women and Other Monsters: Building a New Mythology (Beacon Press 2022).