Find Part 1 to this post here!

The Perils of Studying Virgil

That the erudition of Irish scholars in the early Middle Ages was not always cast in a positive light is reflected in a letter, written nearly two centuries earlier, by Aldhelm, abbot of Malmesbury (d. 709). Aldhelm writes in admonishing language to his student Wihtfrith that he is none too pleased with the latter’s decision to go study in Ireland. He wonders why Wihtfrith would forsake the study of the Old and New Testament to read foul pagan literature, i.e., Virgil, which was apparently being taught in the monastic centres of Ireland. More colourful still is Aldhelm’s language in the oft-quoted passage below:

Quidnam, rogitans quaeso, orthodoxae fidei sacramento commodi affert circa temeratum spurcae Proserpinae incestum—quod abhorret fari enucleate— legendo scrutandoque sudescere aut Hermionam, petulantem Menelai et Helenae sobolem, quae, ut prisca produnt opuscula, despondebatur pridem iure dotis Oresti demumque sententia immutata Neoptolemo nupsit, lectionis praeconio venerari aut Lupercorum bacchantum antistites ritu litantium Priapo parasitorum heroico stilo historiae caraxere.

What, pray, I beseech you eagerly, is the benefit to the sanctity of the orthodox faith to expend energy by reading and studying the foul pollution of base Proserpina, which I shrink from mentioning in plain speech; or to revere, through celebration in study, Hermione, the wanton offspring of Menelaus and Helen, who, as the ancient texts report, was engaged for a while by right of dowry to Orestes, then, having changed her mind, married Neoptolemus; or to record—in the heroic style of epic—the high priests of the Luperci, who revel in the fashion of those cults that sacrifice to Priapus […].[1]

But Aldhelm did not stop there. No, truly, Ireland held further dangers still than the dactylic hexameters of the Augustan poets of old. He continues:

Porro tuum discipulatum ceu cernuus arcuatis poplitibus flexisque suffraginibus feculenta farna compulsus posco, ut nequaquam prostibula vel lupanarium nugas, in quis pompulentae prostitutae delitescunt, lenocinante luxu adeas, quae obrizo rutilante periscelidis armillaque lacertorum terete utpote faleris falerati curules comuntur, […]

Moreover, I, compelled by this foul report, beg your Discipleship, genuflecting, as it were, with arched knee and bent leg, that you in no wise go near the whores or the trumpery of bawdy houses, where lurk pretentious prostitutes with luxury as their pander, who are adorned with the flashing burnish of leg-bands and with smooth arm bracelets, just as ornamented chariots are adorned with metal bosses; […]

It would seem that reading Virgil and engaging prostitutes go hand in hand, the beneficiary being equally worthy of damnation in Aldhelm’s eyes. It is a pity that we never find out whether Wihtfrith actually heeded his teacher’s advice or, indeed, what lines (facetiously penned in hexameter?) he may have tendered in response to assuage his anxious master’s fears. The letter to Wihtfrith, along with many others of Aldhelm’s writings, survives today only in William of Malmesbury’s Gesta Pontificum Anglorum, an early-twelfth-century history of the English bishops. Aldhelm’s letters are contained in Book V of the Gesta, the section of William’s work dedicated to the history of Malmesbury Abbey and to Aldhelm, its founder.

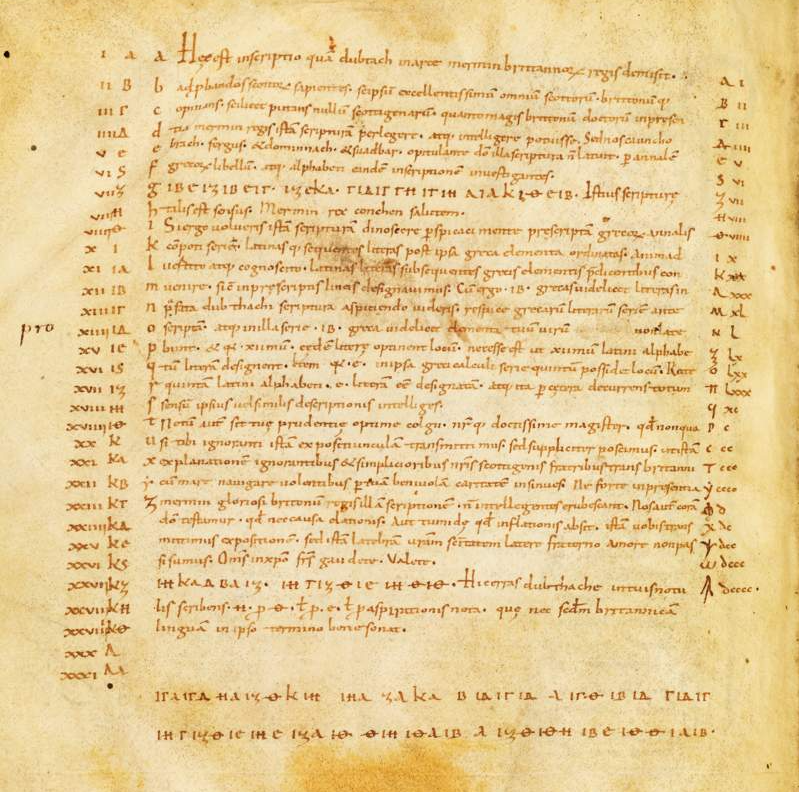

King Alfred and a Reindeer

Having now moved from Ireland, via Wales, into Anglo-Saxon England, we are coming to our final stop on the journey through language contacts, manuscripts, and riddles in North-western Europe. While this section does not contain a riddle or admonition, it deals with one of the most interesting examples of language contact that I have come across. And it involves no lesser a man than Alfred of Wessex himself. As I mentioned before, it is only natural to reflect, when two languages come into contact, how these are both different and alike. When I recently listened to BBC4’s In Our Time podcast on the ‘Danelaw’[2] (referring to both an area of Norse occupation as well as customs and legal practices), one of the speakers, Prof. Judith Jesch of the University of Nottingham, discussed the story of the voyages of the Norwegian tradesman Ohthere during his stay at the court of King Alfred. Alfred had acceded to the throne of Wessex in 871, the only kingdom within Anglo-Saxon England that was not under Norse rule at the time, and later in 886, Alfred negotiated a treaty with the Danish king Guthrum, establishing a border between their two domains. Apart from being a skilled military and political leader, Alfred was also invested in cultural reform and education, looking for inspiration across the Channel to what had been achieved as part of the Carolingian Renaissance. One of the areas that Alfred’s efforts centred on was providing translations of important Latin texts, especially theological and historical works. One of these works was Orosius’ Seven Books against the Pagans, by that time the standard source for world history. At one time, it was even believed that it was Alfred himself who translated the text into Old English, although this theory has now largely fallen out of favour.[3] And it is as part of the Old English Orosius that we find the fascinating story of the voyage of Ohthere to Alfred’s court. Ohthere tells the king that he comes from the northernmost part of Norway, hardly inhabited, and brings him a gift of walrus tusks, containing precious ivory. Then he tells the king that:

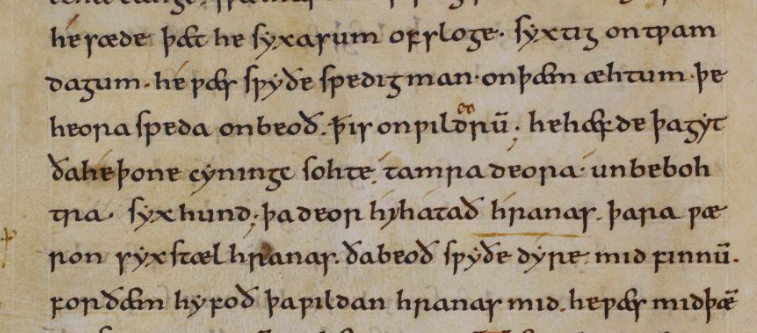

He wæs swyðe spedig man on þæm æhtum þe heora speda on beoð, þæt is on wildrum. He hæfde þagyt, ða he þone cyningc sohte, tamra deora unbebohtra syx hund. þa deor hi hatað hranas; […]

He was a very rich man in those possessions which their riches consist of, that in wild deer. He had still, when he came to see the king, six hundred unsold tame deer. These deer they call ‘reindeer’.[4]

This selection of anecdotes found and lifted from the pages of medieval parchment provides just a glimpse into the fascinating world of medieval Irish, Welsh, Anglo-Saxon, and Norse contacts. And just as the modern student diligently devotes their time to make sense of the difficult Old-Irish Paradigms and Selections from the Old-Irish Glosses, annotating their copy with helpful notes, so did medieval scribes annotate their Latin texts, spelling out difficulties and playing with languages. And as undergraduates and postgraduates apply to the most competitive and most coveted university programmes, either with or without the counsel of an academic mentor or advisor, so did Wihtfrith no doubt make Ireland his educational destination. And no doubt, when Alfred of Wessex received Ohthere at his court, we may not have anticipated learning so much about northern Norwegian fauna. What these examples teach us is that history and language, manuscripts and literature can never be studied in isolation, but must come together to allow us to construct the story of the past. And while the past may be a different country (pace Hartley),[7] they don’t always do things differently there.

Marie-Luise Theuerkauf, Ph.D.

University of Cambridge

[1] Lapidge, M. and Herren, M., Aldhelm: The Prose Works. D.S. Brewer, 1979: 154.

[2] Visit: https://www.bbc.co.uk/programmes/m0003jp7 [last accessed 28/04/19].

[3] Lund, Niels (ed.), Two voyagers at the court of King Alfred: The ventures of Ohthere and Wulfstan, together with the Description of northern Europe from the Old English Orosius. York, 1984: 6.

[4] Lund 1984: 20.

[5] The manuscript is available online here: http://www.bl.uk/manuscripts/FullDisplay.aspx?ref=Cotton_MS_Tiberius_B_I.

[6] Lund 1984: 56.

[7] Hartley, L. P., The Go-Between. Hamish Hamilton, 1953.