Most of us in the English-speaking world have read Beowulf, in translation and in high school. It is generally taught as an ancient text with insights into Anglo-Saxon culture, whispering from our distant past. But can these whispers speak meaningfully to us today, aside from mining historical gems from the text?

Beowulf is a medieval poem about heroes and monsters. But it also a poem cautioning against the destructive forces of violence and greed, the very same combination of forces which most trouble the world today.

For those who read the text in the original language, Beowulf is a playful, at times suspenseful, poem which masks its monsters in ambiguous language and draws verbal parallels between the heroic protagonists and their monstrous antagonists in ways that challenge a reader’s assumptions. And, of course, it was performed!

Are there ways of performing Beowulf, which speak both to then and now? This is the mission behind Grendelkin.

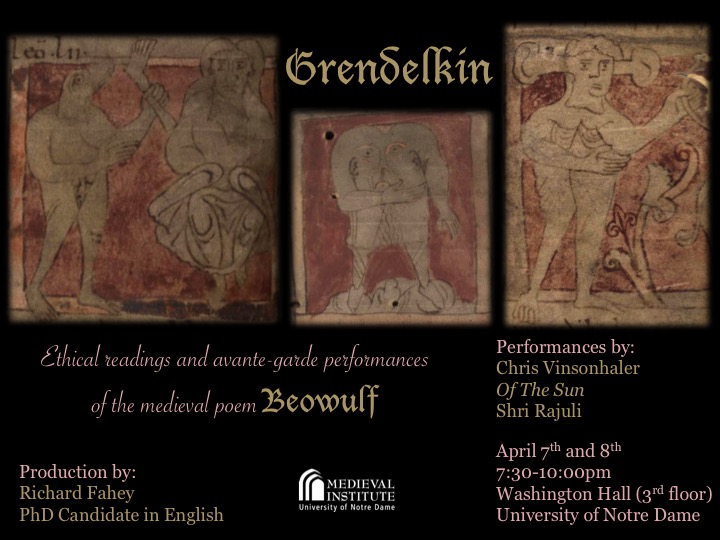

Grendelkin is an upcoming two day production sponsored by Notre Dame’s Medieval Institute, which seeks to highlight the ethical concerns expressed in Beowulf through professional storytelling and avant-garde performance. Grendelkin interrogates the function of reciprocal and sanctioned violence within the text and challenges tribalism and the warrior ethos of the poem, while keeping a modern audience and their contemporary concerns in focus.

Cost: The event is free (no ticket charge) and open to the public. Tickets will be given at the door and programs will be available at the venue.

Dates: 4/7 & 4/8, 2017

Time: 7:30-9:00 with refreshment the following hour both evenings

Place: Washington Hall (third floor), University of Notre Dame

Event Schedule and Artist Biographies:

DAY 1 (Friday, 4/7): Beowulf: A Poem for Our Time

Performance by Chris Vinsonhaler

An award-winning performance, Beowulf: A Poem for Our Time, will roar to life on Friday, April 7, in a program that is free and open to the public. This performance frames her version of Beowulf in both an Anglo-Saxon historical context and in conversation with contemporary current events and cultural knowledge.

The general public is invited, and high school classes are expressly invited. However, because of the sophisticated and violent content, the performance is recommended for adults and young adults only.

Awarded a fellowship funded by the National Endowment for the Arts, Chris Vinsonhaler is an internationally touring artist who also serves as a professor with the City University of New York.

Her performance work has received praise from scholars, poets, teachers, storytellers, and armchair readers. “You made Beowulf come alive even for those who hated reading it,” said Rosemary DePaolo, President of the University of North Carolina, Wilmington. “You made the audience feel that Beowulf, Grendel, and Hrothgar were with us—in the room, and in our time.”

“Vinsonhaler’s Beowulf bristles with an energy and enthusiasm that is both captivating and infectious,” said Andy Orchard, Professor of Anglo-Saxon at Oxford University.

“Beowulf does indeed have something for everyone,” said Vinsonhaler. “It is a dazzling work of poetry, and it is also a knock-em, sock-em piece of pop culture about a Dark Ages super hero. It is somber and thought-provoking, but it is also a lot of fun. That’s what great storytelling has always been about.”

Yet those who are familiar with Beowulf should expect to be surprised. “Beowulf has many surprises in store,” Vinsonhaler said. “The poem is ironic, subversive, grotesque, and darkly comic; and it may even lay claim to be the world’s first murder mystery. Yet, above all, Beowulf is a prophetic work about the death of nations. It presents a world overshadowed by the image of a burning tower and by monstrous acts of avarice, envy, deceit, and revenge. It is very much a poem for our time.”

Now fifteen years into the project, Vinsonhaler has completed a Ph.D. in pursuit of the project. And she believes the secret of the poem is revealed through performance.

“As a professional storyteller, I wondered what would happen if Beowulf were seriously examined and interpreted through performance. Although many questions remain unanswered, one thing that is almost certainly true: Beowulf was meant to be heard, not read. What excites me most, and what I hope to share with others, is that the poem does indeed take on a life of its own when returned to spoken form.”

Chris Vinsonhaler is currently working to revise her translation and has a website designed to help students of Beowulf access the “bones” of the language in order to better understand the poem and its performed context.

DAY 2 (Saturday, 4/8): Haunting Tales of Grendelkin

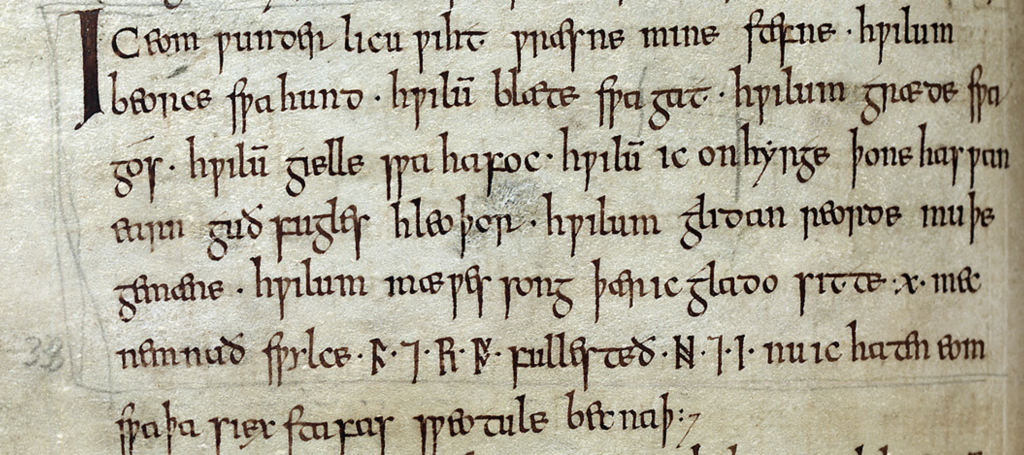

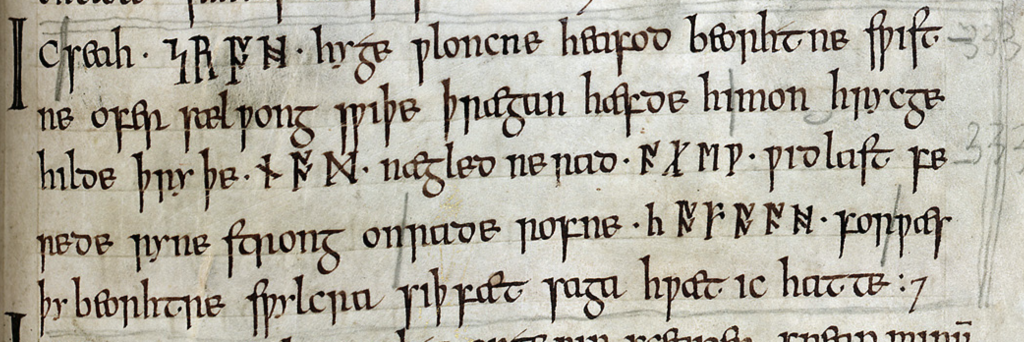

Act 1: Giedd in Geardagum “Songs of Yore”

Recitations by Richard Fahey

with instrumentation accompaniment by Chris Vinsonhaler (harp)

This first act will be comprised of three recitations of short episodes from Beowulf in the original Old English language and accompanied by the bardic harp.

- The Lay of Scyld “Terror and Tribute” is the first of the three lays, and the shortest. Scyld’s Lay establishes a paradigm for heroic kingship in the poem. It tells of the heroic deeds of Scyld Sceffing, as he terrorizes the surrounding nations and exacts his tribute from them.

- The Lay of Sigemund “Murder and Plunder” is the second lay in the series, and tells of the heroic deeds of Sigemund (from the Vǫlsunga saga and associated literature), especially his slaying of a mighty dragon and plundering his treasure. This episode foreshadows the later dragon episode and describes Sigemund in terms similar to the monsters in the poem.

- Grendel’s Approach “Becoming a Monster” is the last section of Beowulf, and describes how Grendel comes from the dark night, through the swamps and into the hall to feast on the men there. Grendel’s Approach isolates the terrifying moments in which the monster finally arrives and confronts both characters and readers for the first time in the narrative.

Richard Fahey is a PhD candidate in the English Department at the University of Notre Dame where his research interests include monstrosity, syncretism, rhetoric and intertextuality in Old English, Old Norse literature and Anglo-Latin literature. In addition to producing Grendelkin, Richard is currently working on his dissertation “Enigmatic Æglacan: Riddling the Beowulf-monsters” which brings the Exeter Book riddles into conversation with Beowulf through lexicographical and stylistic analysis. Richard is also an editor and contributor to Notre Dame’s medievalist blog The Chequered Board and for the affiliate Old English Poetry translation and recitation project.

Act 2: Sceadugenga

Avant-garde performance by ❨❨❨:: Of The Sun ::❩❩❩

with instrumentation by Tom Fahey, Adam Blake and CJ Carr

and dance accompaniment by Wisty Andres, embodying the character of Grendel

Boston sound artist Tom ‘Totem’ Fahey started working with sound and becoming invested in music as far back as elementary school. Forming several bands in his youth, he eventually found himself at Massachusetts College of Art and Design in the S.I.M. program [Studio for Interrelated Media]. Here he took to avant-garde compositions and developed his ear and vision for studio and live event production.

Since then Tom has performed in numerous projects ranging from folk music to experimental noise to black metal, and has done various sound installations and sound design work for local artists and musicians. Tom has worked also as art director for Boston’s annual New Year’s art festival First Night from 2011-2015.

(((::OF THE SUN::))) was started in June 2010 by Tom Fahey and Adam Blake from the ashes of an experimental improvisational sound project called Fractillian, which performed around the Boston area from 2007- 2010. Having taken on the visual projection art of Andrew Goldman, they performed live for the first time in November 2010. (((::OF THE SUN::))) is influenced by Norwegian Black Metal and avant-garde Drone music.

Shortly after forming, the vocal and performative force of CJ Carr joined Fahey and Blake and they performed as a trio for the first time in February of 2011.

In 2012 (((::OF THE SUN::)) started performing with acro-yoga artists Adam Giangregorio and Nicole Leland, which became a regular part of the experience, and in 2015 joined forces with the movement artist Wisty, performing with Grendelkin.

Wisty Andres, originally from Tokyo, Japan, started dancing in Columbus, OH at age 7. She has trained in classical ballet, modern, jazz, latin dancing, stilting, and tumbling. She is an alumna of Interlochen Arts Academy where she performed Les Patineurs, Sleeping Beauty, Viva Vivaldi, Serenade, and other classical and contemporary works. Andres holds an AA in Dance from New World School of the Arts College in Miami, FL.

Andres moved to Boston in June 2013 and performed solo work (Satta under Vatten) at the Boston Contemporary Dance Festival 2013 and has also been involved in several projects with 1000virtuesdance since July 2013. Andres previously worked with Penumbra:Movement as a guest choreographer at the 2014 Dance for World Community Festival and a guest artist in the 2014 Spring aMaSSit concert.

Andres is currently dancing with Urbanity Dance Underground Company, and also a dancer and Resident Choreographer for Penumbra:Movement. She has been presenting works all over the Greater Boston Area as an independent choreographer in various venues, including NACHMO Boston 2014 and 2015, Third Life Studios Choreographer Series, Urbanity NEXT showcases, and Green Street Studios.

The second act, Sceadugenga is inspired by Grendel’s haunting approach to Heorot, and the psychology and mythology surrounding a monster. This piece incorporates the Old English language and raises some of the questions discussed in the current scholarship.

Act 3: Umberhulk

Avant-garde performance by ❨❨❨:: Of The Sun ::❩❩❩

with instrumentation by Tom Fahey, Adam Blake and CJ Carr

and dance accompaniment by Wisty Andres, embodying the character of Grendel

For those interested in previewing a performance, there is video footage corresponding with the above image of❨❨❨:: Of The Sun ::❩❩❩ performing their song “Light” at Boston’s “First Night” in an event called Tribe Vibe.

The third act, Umberhulk, explores the parallelisms between heroes and monsters, such as is found in descriptions of Beowulf and Grendel during their epic battle in the hall.

Act 4: Wrecend

Movement art piece by Shri Rajuli

with instrumentation accompaniment by Tom Fahey (drums and throat singing)

to music by Eivør Pálsdóttir

“Shri” Rajuli (Rajuli Khetarpal Fahey) dances with a spirit that is rooted and ancient. Every movement piece is a ritual for Rajuli. Over time, a fusion of movement influences from around the world has blossomed into her ever evolving dance style, which Rajuli describes as “Temple Tribal Fusion.”

Rajuli has performed and taught for over ten years. She has studied and collaborated with dance professionals all across America. Rajuli is an active movement and installation artist from Boston, and received BFA with Distinction from the Studio for Interrelated Media from the Massachusetts College of Art and Design and is a Rachel Brice 8 Elements Initiate. Her movement art incorporates elements of Indian folk, Ballet, Jazz, African, Haitian, Flamenco, Gothic, Butoh and Modern and modern dance style.

Rajuli has produced movement art shows in the past, such as her recent event Immaculate Portal (7/22/15), which celebrates the experience and journey of motherhood through interpretive dance. Links to additional performances may be found on her website.

Rajuli will be performing the final act of the evening, her piece titled Wrecend, which explore the experience of maternal loss and grief from the perspective of Grendel’s mother.

After the final act, there will be a brief panel discussion of performers in Grendelkin, discussing their art in relation and conversation with some trends in scholarship. At this time, audience feedback and questions are welcomed!

Whether you are a medievalist, an artist, an educator or an enthusiast, we hope you will join us for Grendelkin!

Special thanks to Chris Abram, John Van Engen, Thomas Burman, Megan Hall, Peter Holland, Sara Maurer, the English Graduate School, and especially the Medieval Institute for their support of this project.

Richard Fahey

Art Director and Producer

PhD Candidate

Department of English

University of Notre Dame

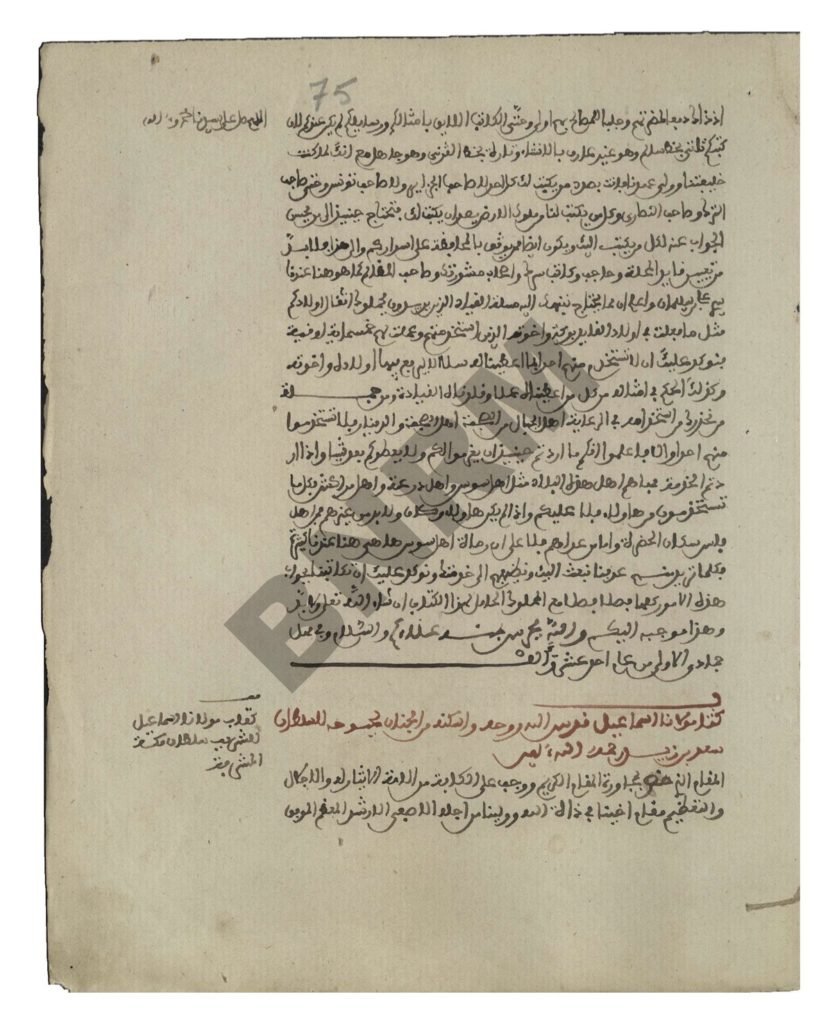

Resources for accessing Beowulf in Old English and its manuscript context

Critical edition: Frederick Klaeber’s critical edition

Student edition: George Jack’s student edition

Electronic edition: Kevin Kiernan’s electronic edition

Digitized Manuscript: British Library, Cotton Vitellius A.xv (Nowell Codex).