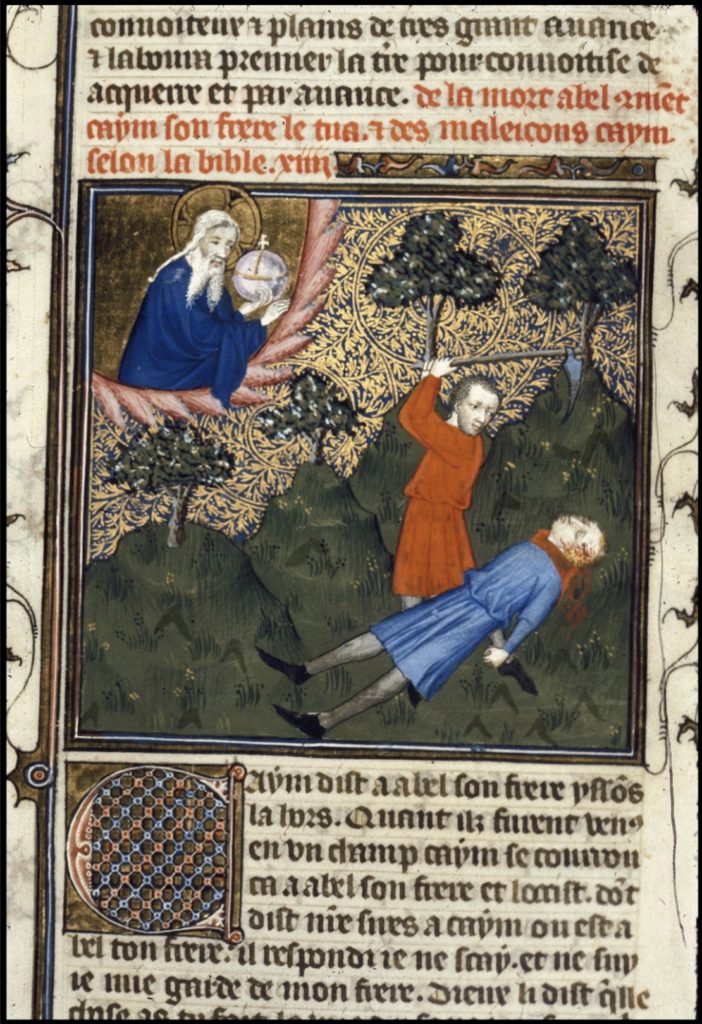

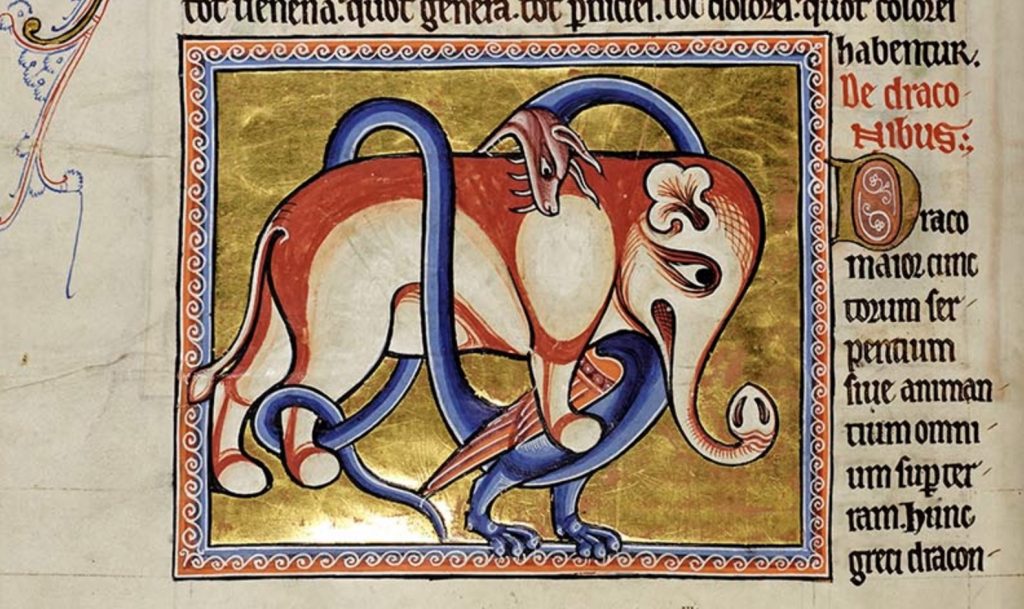

Medieval bestiaries, which flourished during the twelfth and thirteenth centuries, particularly in England, are compendia of brief descriptions of various animals (sometimes plants and stones are included as well), which offer moral or allegorical lessons, and are often colorfully illustrated.

Basic modern definitions often suggest a sort of binary, ontological taxonomy for the creatures in these texts: bestiaries feature “real” animals (or “actual” or “factual” ones, such as dogs, crocodiles, beavers, and elephants), but also “imaginary” ones (or “mythical,” “legendary,” or “fabulous” ones, etc., such as unicorns, phoenixes, and manticores).

Bestiaries themselves don’t appear to distinguish between “real” and “imaginary” animals, in terms of the arrangement of entries or the way that creatures from these two categories are verbally described or artistically depicted;[1] the distinction is a modern and anachronistic one. Furthermore, bestiaries’ inclusion of hard-to-believe anecdotes about well-known creatures who actually do exist (e.g., the stag’s alleged habit of drowning snakes) renders the boundary between “real” and “imaginary” animals, as we might consider it, less firm in these texts. At stake in the discourse of the “real” versus the “imaginary” in bestiaries is our view of medieval thinkers.

One approach to the “imaginary” animals in bestiaries—a very old approach to interpreting mythical creatures, in fact—is rationalistic: positing that even the legends have some basis in reality, and that real animals were, through a combination of misunderstanding and literary transmission, rendered (almost) unrecognizable. Notable proponents of this view in modern times have included T. H. White (1954), and more recently, zoologists Wilma George and Brunsdon Yapp (1991).

Bestiaries, for these scholars, can be read as works of natural history, albeit flawed ones, and we should perhaps extend some generosity to their creators, in light of the limitations of their knowledge. George and Yapp characterize the bestiary as “an attempt, not wholly unsuccessful or discreditable for the time at which it was produced, to give some account of some of the more conspicuous creatures that could be seen by the reader or that occurred in legends.”[2] They suggest, for instance, that the manticore—described in bestiaries as a creature with a man’s face, a lion’s body, three rows of teeth, and a tail like a scorpion stinger—was based on the cheetah; that the unicorn could actually be an oryx; and that the half-human, half-fish siren could be a Mediterranean monk seal.

Reading bestiaries as genuine, sometimes highly faulty attempts at something comparable to modern natural history is not a popular position amongst medievalist scholars of bestiaries. However, the idea of bestiaries as failed pre-modern zoology lingers in some sources aimed at popular audiences. The entry on bestiaries in the Encyclopaedia Britannica, for example, claims that the “frequently abstruse stories” in these works “were often based on misconceptions about the facts of natural history.”

As for the ontological status of “imaginary” bestiary creatures to medieval readers, i.e., whether they believed unicorns, etc. actually existed, this is hard to ascertain, and perhaps of less interest to many scholars than the prospect of examining the messages these rich works articulate on their own terms. Still, the unsupported assertion that bestiary stories were “generally believed to be true” in the Middle Ages, as the Wikipedia page for bestiaries claims, is very much in line with widespread perceptions of the period.

It is an appealing contemporary fantasy, not so much to believe in dragons or unicorns, but to believe that people really believed in them, once—a sort of vicarious experience of enchantment, accomplished not simply by imaginatively engaging with medieval works that depict fantastic animals, but by imagining more credulous medieval readers, and perhaps even by imagining oneself in their place.

To take both “real” and “imaginary” bestiary creatures as the texts present them—not seeking to sieve the factual from the fabulous, not seeking an ordinary, well-known animal behind the remarkable verbal and visual depictions that bestiaries offer—allows for, amongst other things, a certain defamiliarization of the natural world we inhabit.

Playing on the fertile ambiguities of bestiary accounts is a project by The Maniculum (a podcast series which brings together medieval texts and modern gaming, co-hosted by E. C. McGregor Boyle, a PhD Candidate at Purdue University, and Zoe Franznick, an award-winning writer for Pentiment). On the Maniculum Tumblr, readers are offered “anonymized” selections from the Aberdeen Bestiary (i.e., the name of the animal being described is replaced with a nonsense-word to disguise its identity). Contributors are invited to create artwork inspired by the bestiary description itself, rather than their knowledge of what the animal is “supposed” to look like. The results are diverse; the “hyena” entry, for instance, yielded representations of creatures resembling everything from pigs to predatory snails, in a wide range of styles.

Bestiaries continue to fascinate and inspire, centuries after their creation. Below are some medieval bestiary facsimiles and related resources to explore:

- The Aberdeen Bestiary (Aberdeen, Aberdeen University Library MS 24), written and illustrated in England ca. 1200. Digital facsimile, accompanied by commentary, and Latin transcriptions and modern English translations of each folio.

- The Ashmole Bestiary (Oxford, Bodleian Library, MS Ashmole 1511), early 13th century, England, possibly derived from the same exemplar as the Aberdeen bestiary. Digital facsimile.

- The Worksop Bestiary (New York, Pierpont Morgan Library, MS M.81), ca. 1185, England. Digital facsimile.

- The Medieval Bestiary: Animals in the Middle Ages, a website on bestiaries by independent scholar David Badke. Includes indices of bestiary creatures, cross-referenced with manuscripts and relevant scholarship, as well as galleries of medieval illustrations.

- Into the Wild: Medieval Books of Beasts, YouTube video by The Morgan Library & Museum.

Linnet Heald

PhD in Medieval Studies

University of Notre Dame

[1] Pamela Gravestock, “Did Imaginary Animals Exist?” in The Mark of the Beast: The Medieval Bestiary in Art, Life, and Literature, ed. Debra Hassig (New York: Garland, 1999), 120.

[2] Wilma George and Brunsdon Yapp, The Naming of the Beasts: Natural History in the Medieval Bestiary (London: Duckworth, 1991), p. 1.