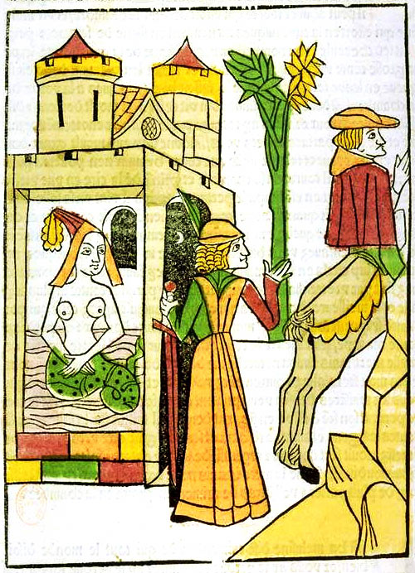

I recently gave a guest lecture during Dr. Megan Hall’s fall 2024 course entitled “Witches, Warriors, and Wonder Women: Women, Power, and Writing in History.” To prepare for my visit, students read excerpts from Jean d’Arras’s Melusine; Or, the Noble History of Lusignan as translated and edited by Donald Maddox and Sara Sturm-Maddox (Penn State UP, 2012). The story of Melusine, for those not in the know, is steeped in folklore. Various accounts of the tale involve a fairy woman named Melusine who takes on a half-serpent form from the waist down during part of the week and must hide this from her lover lest they suffer the consequences! Jean’s version of the tale, which dates to 1393, offers an account of the founding of the Lusignan dynasty and how Melusine, a half-fairy woman cursed to assume a half-serpent form on Saturdays, played a major role in its establishment and prestige. The House of Lusignan in its heyday counted Crusader kings among their ranks. My goals were to get Dr. Hall’s students thinking about the representation of non-humanness, the ways in which Melusine wields and exercises power, the significance of relating a historical family’s lineage to a fairy founder, and the truth claims that Jean makes. Certainly a tall order for our hour and fifteen minutes together, but trust me: the students rose to the occasion!

The text’s prologue immediately draws you into Jean’s narrative web. I find it striking how he claims to weave together various sources and reconciles them with his Latin Christian faith so that he can then go on and discuss Melusine. He references Aristotle and Saint Paul’s Epistle to the Romans in his discussion of marvels. Yet, he writes that “even those well versed in science can hear or see things they cannot believe but which are nonetheless true. I mention these matters because of the marvels that occur in the story I am about to tell you, as it pleased God my Creator and at the behest” of his patron, John, Duke of Berry (20). The marvels that Jean references, of course, are the ones associated with fairy magic and power. Fairies—and Jean references Gervase of Tilbury’s account of fairies for this portion of the prologue—can take on the form of beautiful human women. They can marry human men and even bear children with them, but these men must make promises to their fairy wives and uphold them. These promises can range from a prohibition from seeing the fairy wife nude to never seeing her in childbed.

According to Jean’s summary of Gervase, “[a]s long as these men kept their promises, they increased in rank and prosperity, but at the moment they broke them, they lost the women, and their fortunes slowly declined” (21). In a few short paragraphs, Jean not only tries to bolster the authority of his tale with these references to notable predecessors, but he also builds the world of fairies for his audience. Melusine then is but one example of how the marvel of fairies can operate, leading to some major consequences. As a class, we tried to make sense of Jean’s claims and how he reconciles fanciful fairy tales with what seemed like major authoritative sources. Surely, there must be something special about fairies—why else would Jean spend so much time insisting on their existence and the truth of the tale he is about to share? Furthermore, why would a powerful family like the Lusignans want to connect their family line to a fairy? After discussing the prologue, we were ready to tackle the rest of the text.

The tale unfolds as Jean recounts Melusine’s first encounter with her soon-to-be husband, Raymondin. Melusine’s enchanting beauty causes Raymondin to fall in love at first sight. The two marry under one important condition: that he never attempt to see her on Saturdays. Ever! Unbeknownst to Raymondin, on Saturdays Melusine keeps away from him and hides the fact that her lower half takes on a serpentine form. For years, they enjoy a prosperous marriage. They have numerous sons together, and the majority of them, according to Jean, go on to be rulers of Cyprus, Armenia, and more. Melusine takes on the role of master planner and architect. She builds fortresses and advises her husband on how to increase his wealth and prestige. This marital bliss, however, comes to an end when Raymondin spies on Melusine and discovers her Saturday secret. Though he keeps it to himself for some time, in a moment of anger he reveals knowledge of her weekly transformation and weaponizes it against her in an argument. Since he breaks his promise to her, Melusine takes leave of him. When his death nears, she returns in the form of a dragon.

Dr. Hall’s students truly impressed me with their thoughtful engagement with the text. We had conversations about female agency and power. I asked them to think about narratives parallels in the text and the role of curses and magic across similar events. I pointed out how when fairies and humans reproduce, their progeny bear remarkable physical features ranging from gigantism to having an unusual number of eyes. We pondered what a prestigious family like the Lusignans would gain from claiming a half-fairy woman as a major progenitor and have her powers be a major explanation for their wealth and prestige. I had so much fun diving in the text with them. It was clear to me that they had plenty to say about the ways in which the text represents various interpersonal dynamics. Melusine’s fairy qualities add to her allure and ability to influence those around her, for better or worse.

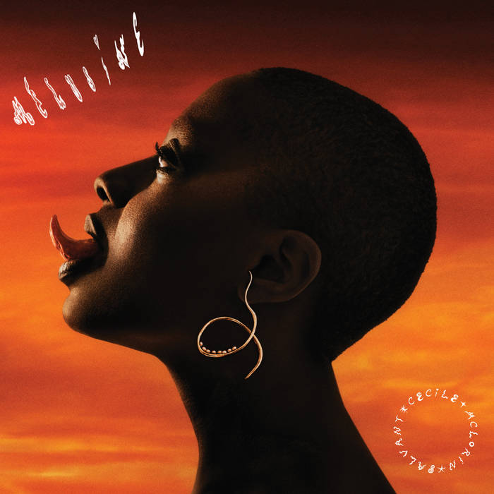

As our short time together came to an end, I asked them to think about Melusine’s legacy and afterlives. The legend of Melusine has endured and continued to captivate over the centuries. The major coffee chain Starbucks, for instance, has a rendition of Melusine as its logo (though the company’s own lore obscures this link!). For the jazz fans reading, please know that there is an incredible musician by the name of Cécile McLorin Salvant, whose seventh solo album, Mélusine, was released in March 2023. In the description for the album on the website Bandcamp[1] , Salvant unpacks the significance of the Melusine story and how it resonates with her.

What I find striking about Salvant’s reflections on the Melusine story is her reading of how significant gazes are. She shares that the tale is “also the story of the destructive power of the gaze. Raymondin’s sword pierces a hole into [Mélusine’s] iron door. His gaze does too. The gaze is transformative and combustible. She sees that he is secretly seeing her. Her secret is revealed. This double gaze turns her into a dragon.” Dr. Hall’s students definitely picked up on the power of the gaze but also recalled that it is a power that had to be weaponized before it could transform. In other words, when Raymondin first sees Melusine’s true form, he keeps his transgression to himself. His gaze is a breach of trust, and Melusine knows that her husband spied on her but decides to forgive him because he maintains her secret. However, when he becomes enraged, his anger causes him to lose all discretion. Raymondin angrily reveals that he knows about Melusine’s weekly transformations and resents her. The students recognized that it was precisely this resentment that made the revelation of the secret so powerful.

Another powerful way that Salvant relates to the Melusine story is through the idea of hybridity. Salvant was born in the United States to a French mother and a Haitian father. She spent ample time studying music in Aix-en-Provence, France. She is intimately familiar with negotiating various languages and cultures. When discussing the album Mélusine, she says it is “partly about that feeling of being a hybrid, a mixture of different cultures.” Though we did not get ample time to discuss Salvant’s feeling of hybridity, I do love how she draws a connection between her experiences and that of the legendary Melusine, who also had to navigate different cultures and human/non-human experiences. I find it beautiful that the tale of Melusine endures after all this time and can inspire people to explore the intersections of their own identity and reflect on how they experience the world.

While students were packing up their bags and heading out the door, one student lingered behind and wanted to keep the conversation going. This student wanted to talk about how Melusine’s representation of fairies as having conflict with God struck them; in their culture, fairies and even gnomes are guardians and protectors. The enthusiasm that the student exuded was infectious! And reflecting on this moment now, this just speaks even more to the allure not just of Melusine but of the magical realm at large: a space of play and imagination, sure, but also of power relations, of fidelity, of exploring identity, and so much more.

Anne Le, Ph.D.

Public Humanities Postdoctoral Fellow

Medieval Institute

University of Notre Dame