When more than a dozen undergraduates successfully banded together last year to petition the administration for me to teach the first ever course in Old Norse language and literature at my (now former) institution, I vowed not to disappoint them.[1] Knowing that these students would likely never have another opportunity to spend a semester learning and reading Norse in a formal setting, I soon realized that in two one-hour meetings per week over a single semester we could hope for little more than a forced march through any standard textbook, yielding some sense of the rules of the language but no real experience reading it.

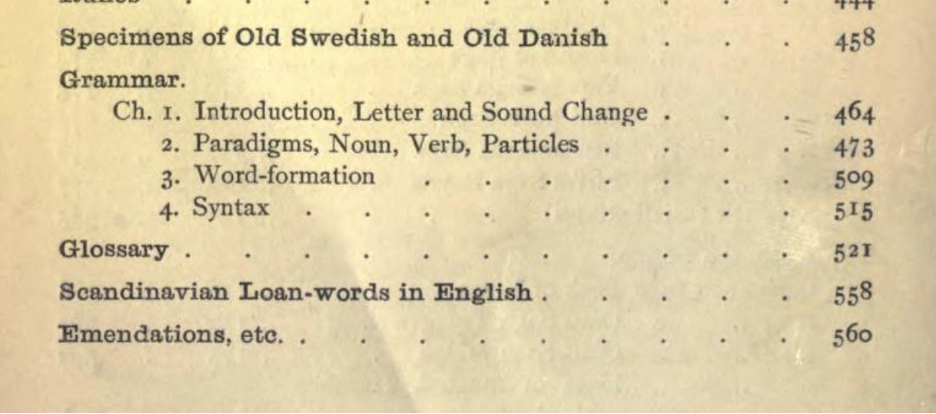

Broadening my search, I came across Guðbrandur Vigfusson’s 1879 Icelandic Prose Reader. Vigfusson recommends jumping right into reading, ideally beginning by muddling through the Gospel of Matthew, with which he assumes students will be familiar, before moving on to a shorter saga—he recommends Eirik the Red. He offers this advice:

The beginner should at first trouble himself as little as possible with grammatical details, but try the while to get hold of the chief particles, the pronouns, and a few important nouns and verbs—the staple words of the language…The inflexive forms are of less import; they will be more easily learnt and better remembered, if they are allowed to grow bit by bit on the mind, as they occur in the reading. Grammar is, after all, but the means to an end, and much of one’s freshness and power of appreciation is lost, if it is incessantly diverted from the subject before one, to the ungrateful study of dry forms.[2]

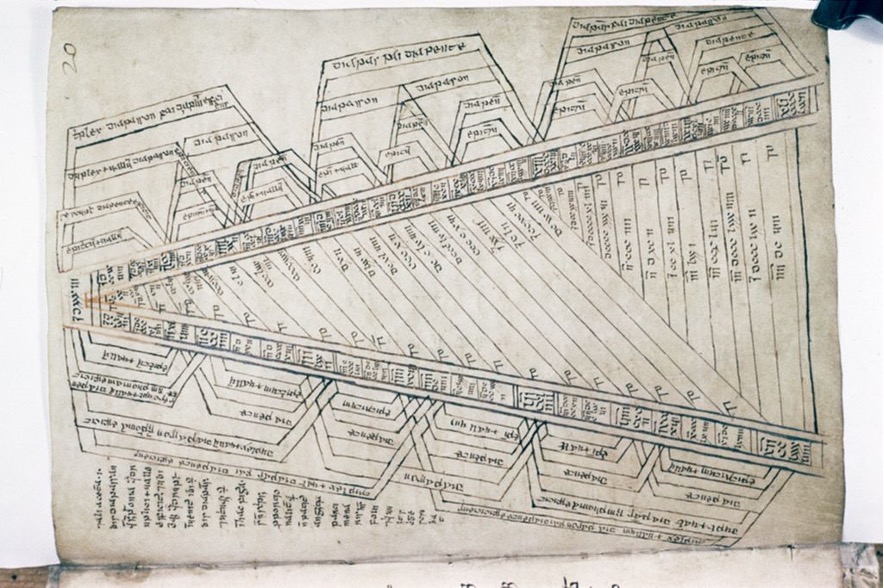

Though the reader does come equipped with a brief grammar consisting primarily of tables and charts, Vigfusson underscores his grammar-deemphasized, reading-first method by featuring the texts first in the volume, grammar second.

Though Vigfusson gave very little concrete advice for teaching besides a general idea to dump students in and let them swim, it got me thinking about how else we might teach and learn old north germanic languages. How did medieval students and teachers approach language learning?

The Anglo-Saxons (despite or perhaps due to King Alfred’s lamentations about the state of Latin learning in his realm) were particularly accomplished language learners, as anyone considered truly literate had to read and write a completely foreign language—Latin. This literacy included many skills besides grammatical analysis. To quote R.W. Chambers, “their aim was to read Latin, write Latin, and dispute in Latin.”[3] Recalling Vigfusson’s suggestion to start with the Gospel of Matthew, the youngest students of written Latin would begin with the Psalms, which they had previously learned by heart, along with the letters of the alphabet and various Latin prayers.[4] The upshot is, medieval students had a lot of the target language in their ears and memorized by heart before they ever began a program of study directly aimed at mastering grammar, learning to read, and creating in the language.

Then they’d move on to the Latin colloquy, question-and-answer dialogues meant to be memorized, acted out, and expanded through creative variation. One of the best-known colloquies, written for young scholars by prolific homilist and grammarian Ælfric of Eynsham at the turn into the eleventh century, was paired close to the time of Ælfric himself with an interlinear Old English gloss. I’d like to suggest a way of using this text in class in a way that goes beyond reading or translating the Old English (or the Latin, for that matter).[5]

The early part of the colloquy is set up as a question-and-answer between the teacher and a classfull of students, who take the parts of people working diverse jobs, a ploughman, a monk, a hunter, a cook, etc.

Here the teacher (perhaps played by one of the students) introduces us to the ploughman.

Hwæt sæᵹest þu, yrþlinᵹc? Hu beᵹæst þu weorc þin?

Eala, leof hlaford, þearle ic deorfe. Ic ᵹa ut on dæᵹræd þywende oxon to felda, and iuᵹie hiᵹ to syl; nys hit swa stearc winter þæt ic durre lutian æt ham for eᵹe hlafordes mines, ac ᵹeiukodan oxan, and ᵹefæstnodon sceare and cultre mit þære syl, ælce dæᵹ ic sceal erian fulne æcer oþþe mare.

A passage like this gives ample opportunity for working in the target language even beyond memorizing and acting out the dialogue (both excellent for building vocabulary and familiarity with grammatical structures). It also allows for imitation and creative response to a series of questions based on the text.

One question is already built into the dialogue.

Eala yrþlinᵹc, hu beᵹæst þu weorc þin?

- Ic ᵹa ut on dæᵹræd þywende oxon to felda, and iuᵹie hiᵹ to syl.

But we can ask other questions that test comprehension and encourage active imitation.

For example:

Hwæt þēoweþ sē yrþlinᵹc ut to felda?

- Sē yrþlinᵹc þēoweþ to felda þæs oxon.

Even without knowing exactly how to conjugate the verb, the student gets to employ the correct form in context through recognition and imitation. I say “þēoweþ,” and the student recognizes it as the form needed in the response.

I can drill conjugation, though, if I want:

Eala yrþlinᵹc, hwæt þēowst þu to felda? (Exaggeratedly pointing a finger at the student to emphasize the second person singular pronoun)

- Ic þēowe þæs oxon.

The student will quickly begin to recognize that “þēowst þu” needs “ic þēowe” as a response. If a student says “ic þēowst” or similar, I might repeat back “þu þēowst, ic þēowe” (with approriate finger pointing) and move right along.

We can work with different verbs:

Eala yrþlinᵹc, hwæt iugast þu to syl?

- Ic iugie þæs oxonto syl.

And play with conjugation:

Hwæt iugiaþ sē yrþlinᵹc to syl?

- Sē yrþlinᵹc iugiaþ þæs oxon to syl.

But there are plenty of other questions we could ask about the same bit of dialogue.

Eala yrþlinᵹc, hwaenne gæst þu ut to felda?

- Ic gā on dæᵹræd to felda.

Hwon gæþ sē yrþlinᵹc ut to felda?

- Sē yrþlinᵹc gæþ ut to felda for eᵹe his hlafordes.

Students might start out with one- or two-word responses. “Yea.” “Oxon.” “On dægræd.” But with encouragement and practice with mirroring back much of the content of the question, they will start to put together more complex utterances.

I might ask:

Hwæþer sē yrþlinᵹc gæþ ut to felda nihtes?

- Se yrþlinᵹc ne gæþ ut to felda nihtes. Sē yrþlinᵹc gæþ ut to felda on dæᵹræd.

or

Hwæþer sē yrþlinᵹc willaþ gan ut to felda?

- Se yrþlinᵹc ne willaþ gan ut to felda. Sē yrþlinᵹc gæð ut to felda for eᵹe his hlafordes.

These examples give some idea of the approach I’ve used, alongside extensive reading of accessible texts, to great result in my Old Norse and Latin classes. The method can be applied to other readings, even if you spend most of the class translating. Pull out a few sentences you’d like to drill down into and ask questions about in the target language.

As a postscript, we did read the gospel of Matthew and the saga of Eirik the Red, and my former students have kept up a Norse reading group, without further help or interference from me.

Rebecca M. West, Ph.D.

The Center for Thomas More Studies

Hillsdale College

[1] An earlier version of this material was presented at ICMS 2024.

[2] Vigfusson, An Icelandic Prose Reader, vi.

[3] R. W. Chambers, Thomas More, 58.

[4] See Garmonsway, Ælfric’s Colloquy, 12.

[5] I took inspiration from the Latin colloquy in developing new materials for my Old Norse class, but the teacher of Old English is saved this laborious step.