Animal symbolism is an important part of the visual imagery of Robert Eggers’ The Northman, released in 2022. But where do they come from? What do they mean?

Hamleth take part in Heimir the Fool’s animalistic ritual in The Northman (2022).

Anyone who has seen The Northman knows that director Robert Eggers is interested in history and mythology. In a recent interview with Slate, he went into considerable detail about the archaeological and literary sources for many of the events and images of his latest film. Snippets of archaeological evidence from the Orkey isles, the Osberg tapestry, and Snorri’s Edda are all woven into his story.[1] It’s also no secret that Eggers’s films lean heavily on animal symbolism: goats and gulls are everywhere in The Vvitch and The Lighthouse.[2] I was therefore surprised that, in his Slate interview, Eggars didn’t touch on one area that seemed ubiquitous in his latest film: the motif known in Old English scholarship as ‘the beasts of battle.’

What are the Beasts of Battle?

Simply put, the ‘beasts of battle’ are the ravens, wolves, and eagles who come to devour the slain on the battlefield. Though they are staples of early Germanic literature, their purpose remains pretty mysterious. When Arnorr Jarlaskald, the 11th century Icelandic poet, commemorated the battle of Nesjar, fought between King Olav Haraldsson and Earl Svein Hakonsson of Lade in 1016, he wrote:

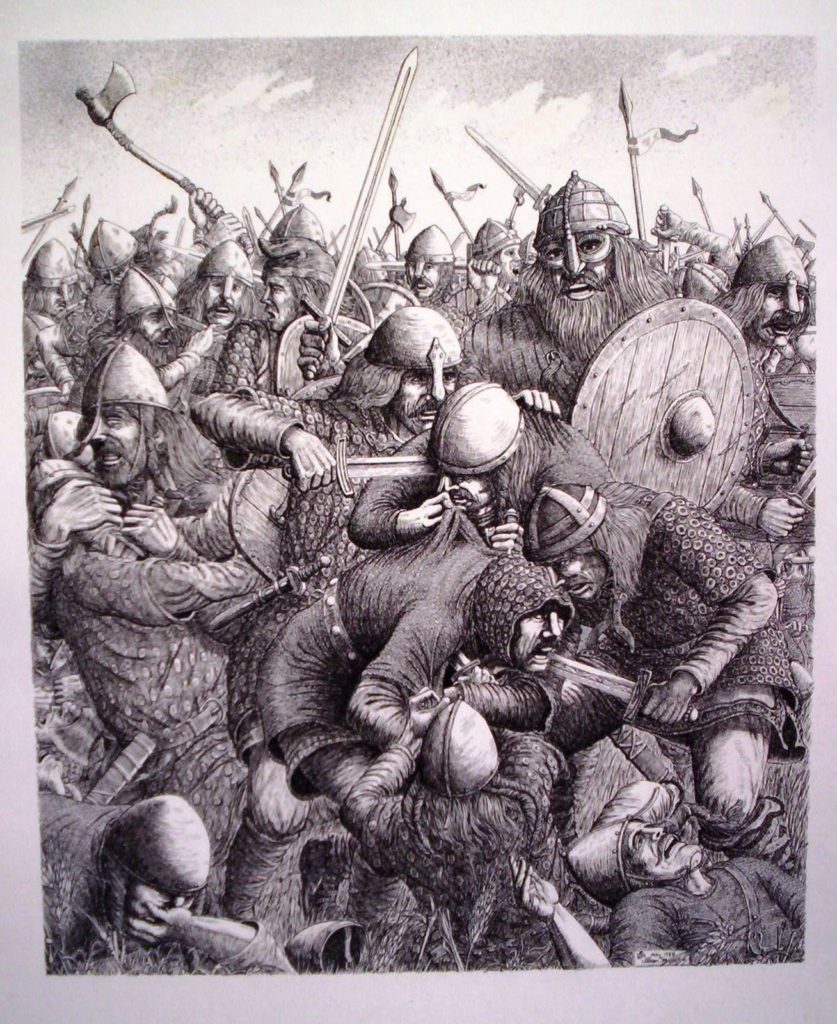

Sandy corpses of [the loser] Sveinn’s men are cast from the south onto the beaches; far and wide people see where bodies float off Jutland. The wolf drags a heap of slain from the water; Olav’s son made fasting forbidden for the eagle; the wolf tears a corpse in the bays.[3]

The beasts help themselves to the dead, and the dead are reduced to food for the beasts. In Egil’s saga, the 11th century poet Egil Skallagrimsson records that his father was a werewolf, who ripped out a man’s throat with his teeth and was nourished by the blood.[4] Even in the complex mythology of the Vikings, carrion eaters are there to consume corpses. The wolf Fenrir, son of Loki and the giantess Angerboda, will be magically chained until Ragnarok (the Norse Doomsday), at which point he will fight and swallow Odin. His purpose is foretold in the Edda, and the very act of chaining him points towards this dark day when he will devour the dead.

The beasts are also a feature of Old English poetry, one of the few markers that hint at literary traditions once shared across northern Europe and now sadly lost. In 991, near the town of Maldon in Essex, England, Earl Byrhtnoth of Mercia led an army into battle to repel his enemy Olaf’s Viking invasion. Byrhynoth suffered a major defeat, which was immortalized a century later in an anonymous poem called ‘The Battle of Maldon.’ In the poem, just before the armies clash, the poet writes that ‘Hremmas wundon, earn æses georn’ (‘ravens circled, eagles eager for food,’ 106-7).[5] They are a dark symbol of fate, of the inevitable slaughter of battle. In fact, the poet calls the Vikings ‘wælwulfas,’ ‘wolves of slaughter’ (96), a role that Amleth inhabits fully in Eggers’ The Northman. Griffith summarized the ‘beasts of battle’ trope thus: ‘in the wake of an army, the dark raven, the dewy-plumaged eagle and the wolf of the forest, eager for slaughter and carrion/food, give voice to their joy.’[6]

The Meaning of the Beasts of Battle

But what do these beasts mean? Beyond their bloodlust, what function might they play? Clearly they are closely connected to battle, a terrifying and ever-present reminder of the ultimate price humanity pays for war. But they also seem to be about dying as an act of nourishment. Old Norse poetry was interested in the borders between human culture and the natural world typified by processes like ‘birth, the unpredictable tenor of life (where Fate was operative) and death.’[7] Death and eating carrion are both natural processes, but human conflict is not. By eating the dead, the wolves and ravens bring the human into their natural reality. Death feeds them so that they can thrive; it’s a process of naturalizing humans, but also about a cycle of death and life. One gives life to the other. Of course, the animals are also mythological. As we’ve seen, the wolves have a mythological counterpart in Fenrir, as well as Odin’s wolves Freki and Geri (‘Ravener’ and ‘Greed’). Thor’s ravens Hugin and Munin, who travel the earth each day to bring him wisdom and prophetic knowledge, are supernatural versions of the ravens who fly over the battlefield. So these beasts of battle are part of the mythological story of the Vikings, as well as the natural cycles of life and death.

In The Northman, Amleth and his father take on the wolf as a totemic animal. In his Slate interview, Eggers acknowledges that young Amleth’s coming-of-age wolf ceremony, led by the Fool in a cave, isn’t drawn from any specific Viking ritual. The setting is derived from a burial chamber found in the Orkney Isles, and the Fool’s ceremonial rattle comes from an archaeological find, and plenty of creative license is taken with them.[8] However, it establishes a connection between Amleth and the wolves from the very beginning of the film. We see him acting as a wolf-pup in the ritual deep in the earth, and then becoming a wolf as a berserker and, as though he were Egill’s own father, ripping out a man’s throat. Historically, berserkers were feared warriors whose ferocity on the battlefield was legendary: they were said to feel no pain. It’s not clear how Viking berserkers developed this immunity—Eggers accounts for it in his film via a trance-inducing ritual. As he torments his uncle, Amleth continues to embody the ferocity and cunning of the wolf. In a revenge tragedy like The Northman, it’s only fitting that the main character’s totemic animal is also a prophetic foretelling of his own death.

Amleth’s father is a nobleman called the Raven Lord, and at several moments a black raven appears to remind Amleth of his duty, as though his father is watching over him. His hero’s journey in The Northman is to avenge his father’s death. But the raven was a symbol of wisdom—a creature that can see the present and the future. Its presence hints at the death that follows Amleth. When he reaches Iceland, Amleth kills his uncle’s eldest son and Amleth’s half-brother, Thórir. When Fjölnir finds the body, it is surrounded by hundreds of ravens. Death has come for Fjölnir and his family. The Raven Lord’s vengeance is near at hand. But in the final showdown between Amleth and Fjölnir, there is no winner. Each kills the other. The ravens were waiting for both of them, and they will feed on them in death. Both men are absorbed into the natural world, and their deaths will nourish the carrion-eaters. In fact, their death also ensures the survival of Amleth’s own son and daughter, who are taken to safety by their mother Olga. But the blood that was spilled in their name—Fjölnir’s entire family, his soldiers, his friends—is inescapable.

The animals of The Northman are companions, tribal markers, but also dark omens of the inevitable death to come. Their presence reminds Amleth, and the audience, that death—his death—is always near at hand. Perhaps The Northman is a piece of Viking literature not because of its longships, Thor’s hammers, Valkyries, but because, in the end, the only certainty is Fate.

Will Beattie

PhD Candidate

Medieval Institute

University of Notre Dame

[1]Rebecca Onion, ‘The Real-Life Inspiration Behind The Northman’s Wildest Scenes,’ Slate [Accessed 5/15/22].

[2]Perri Nemiroff, ‘The Lighthouse Director Robert Eggers Teases What the Seagull Means,’ Collider [Accessed 5/12/22]; Padraig Cotter, ‘The Witch’s Black Philip Explained,’ Screenrant [Accessed 5/12/22].

[3]Whaley

[4]Egill’s saga.

[5]Battle of Maldon.

[6]M. S. Griffith, ‘Convention and Originality in the Old English “beasts of battle” typescene, Anglo-Saxon England 22 (1993), 184.

[7]Margaret Clunies Ross, A History of Old Norse Poetry and Poetics (2005), 93.

[8]Onion, ‘The Northman’s Wildest Scenes’ [Accessed 5/15/22].