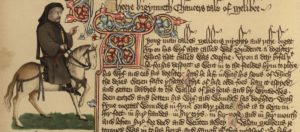

When the pandemic strikes, and the trusted authorities are without a sure remedy, people extend their search for a cure, and in their desperation many resort to more unorthodox means of healing associated with alternative forms of authority and knowledge. Some of the most famous medieval tales are set in times of plague when folk fled to the countryside to avoid exposure to pestilence, as in Giovanni Boccaccio‘s Decameron and Geoffrey Chaucer‘s grim “Pardoner’s Tale” from his Canterbury Tales (which were themselves modeled on Boccaccio‘s collection of stories).

Medieval historian John Aberth writes of the plague known as Black Death, “for this pestilential infirmity [of 1348], doctors from every part of the world had no good remedy or effective cure, neither through natural philosophy, medicine [physic], or the art of astrology.” Aberth adds that although there were no medical solutions, those peddling in various cures could profit from a plague, and he argues that “To gain money some went visiting and dispensing their remedies, but these only demonstrated through their patients’ death that their art was nonsense and false” (The Black Death, 37).

In the Middle Ages, whenever plagues hit, people’s fear of the disease quickly resulted in a lack of faith in traditional authorities, at times followed by scapegoating. The later phenomenon has been observed with respect to xenophobic conspiracy theories targeting marginalized groups, which alleged that Jews were poisoning wells (and sometimes gypsies and witches) in order to spread the Black Death during the later part of the medieval period. And, as Samuel K. Cohn observes, it was then, “Not until the late sixteenth century did authorities once again arrest people suspected of spreading the plague through poisons and tampering with food; these later waves of fear, however, did not target Jews as the principal suspects; instead, witches or hospital workers were now persecuted” (“The Black Death and the Burning of Jews,” 27).

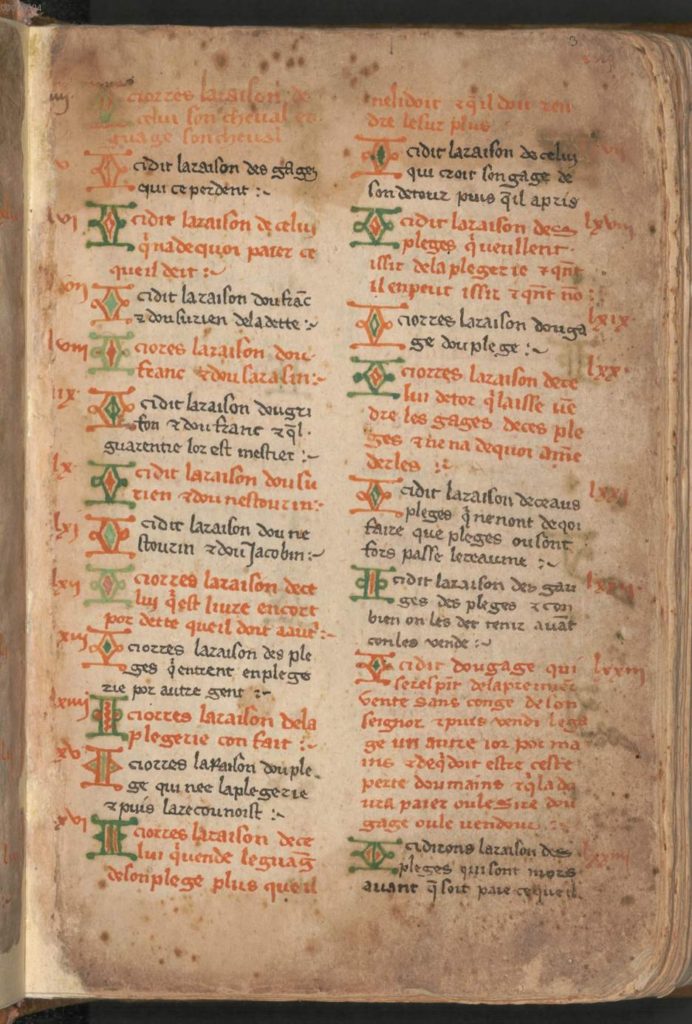

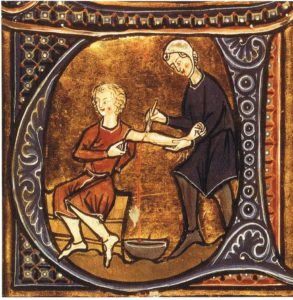

Of course, in the earlier medieval period, when plague descended and church authorities—with all their medical knowledge and spiritual wisdom—were without a cure, medieval people might understandably turn to the other major source of authority in their lives, their kings and secular rulers, for guidance. We see this phenomenon manifest in the medieval belief that French and English monarchs (including saint-kings such as Saint Louis IX and Edward the Confessor) possessed miraculous healing powers. In time of plague, this gesture served to legitimize royalty as divinely sanctioned and win favor with the people, who could understandably become more restless during times of epidemic and pandemic.

Although kings and queens were often unskilled with respect to medical knowledge, especially by comparison to the clergy and university doctors, this sort of magical thinking and desire to imbue a leader with supreme knowledge and boundless inherent wisdom (despite their often limited information and experience) presents a totalitarian image of a ruler, which relies on public ignorance in order to reinforce the notion of a divinely organized, rigidly hierarchical society. It is a form of hero worship which knows no bounds.

As J. N. Hays points out, “the healing touch was a product of political motives, at least in part. But it coincided with a widespread belief in kings as magicians, endowed with near-divine powers” (The Burden of Disease, 33). This political motive leveraged popular belief in the royal touch to solidifying the claim that monarchs were chosen by God and thus superior in both the spiritual and political realms.

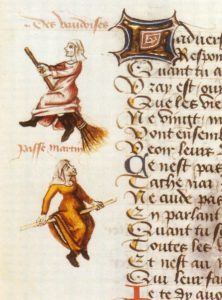

If the king’s touch failed to heal, or one simply did not have access to a royal hand, there was always the other—unspoken and taboo—source of power: magic and witchcraft. As Catherine Jenkin notes “During Venice’s plague outbreaks, notably 1575–1577 and 1630–1631, the population, desperate for a cure, turned to both sanctioned and unsanctioned healers. The wealthy consulted physicians; the less wealthy consulted pharmacists or barber-surgeons; the penitent consulted clergy; and the poor or desperate consulted streghe, or witches” (“Curing Venice’s Plagues: Pharmacology and Witchcraft,” 202). Desperate times called for desperate measures, and without any effective treatments available, everything was on the table.

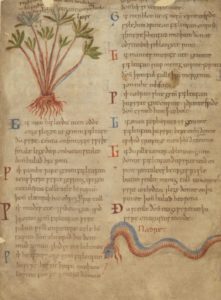

Still, the Middle Ages suffers from a somewhat inaccurate reputation with respect to religious and learned views on the magic, which until the later period regarded folk healing and herbal remedies as mere superstitions, though throughout the period, “witchcraft was universally illegal under both sacred and secular law and even healing magic might be considered heretical” (Jenkins, 204). Nevertheless, folk traditions were generally considered relatively unthreatening by church authorities, especially compared to popular medieval heresies, which argued for unorthodox, though often quite learned, interpretations of Christianity, such as the Catharism & Lollardy, and heretical groups such as the Knights Templar, Hussites & beguines to name a few that drew special attention in the period prior to the advent of the Protestant Reformation.

Furthermore, folk healing was sometimes efficacious, and Helen Thompson has recently argued for a connection between herbal remedies and modern pharmacies and drug markets.

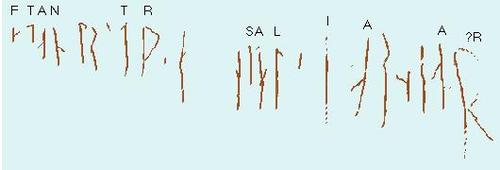

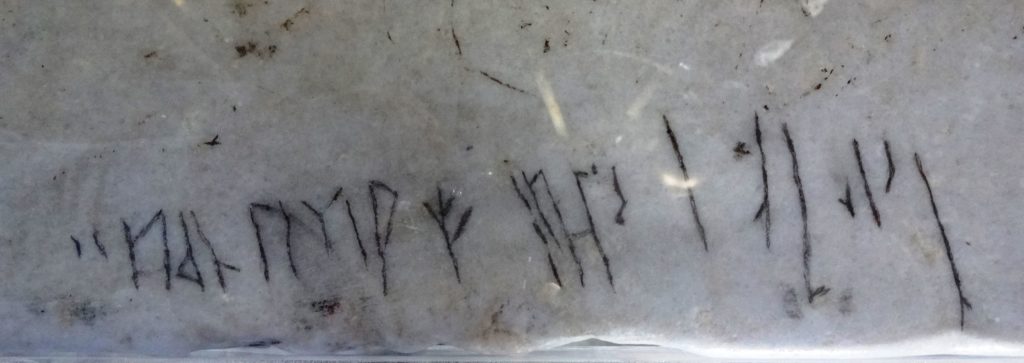

Richard Kieckhefer famously categorizes magic in the Middles Ages as either “natural” or “demonic” in orientation. Folk healers, and most so-called witches, (especially during the earlier period) are regarded by Kieckhefer as practitioners of the former, while seemingly more learned necromancers, who adapt and pervert Christian rituals, are considered practitioners of the later category of magic (and feature later in the period). Scholars such as Aberth, Kieckhefer, Jenkins, Brian Levak and others have each demonstrated a relationship between a rise in magic and the Black Death in Europe (Aberth, The Black Death; Kieckhefer, European Witch Trials; Jenkins, “Curing Venice’s Plagues: Pharmacology and Witchcraft”; Levak, The Witch Hunt in Early Modern Europe).

Desperate people might pursue illicit measures to procure a remedy for pestilence, and as a result interest in magic cures, protections, spell, talismans and wards increased alongside demand. Indeed, it is possible that this contributed to theories that witches poisoned wells and ultimately the hysteria surrounding early modern witch-hunts.

It is important to note that, while the church authorities generally maintained that magic was demonic illusion, the rise of universities gave way to a learned study of “natural magic” in the form of the pursuit to unlock the occult powers in the natural world [i.e. God’s creation]. Hayes observes how “Natural magic, which attempted to understand the hidden powers of nature, was bolstered by philosophy as well as by religion. These relations were clearest in the late Middle Ages and the period of the Renaissance, when neo-Platonic doctrines gained wider currency among thinkers. Neo-Platonic beliefs insisted on the complete interrelation and mutual responsiveness of the different phenomena of the universe” (The Burdens of Disease, 81).

This approach became more widely acceptable leading up to and during the scientific revolution, especially the medical theories of the ancient physician Galen [130-210 CE], and so what Kieckhefer might categorize as natural magic in the later period bifurcates into two distinct subtypes—the highly learned, quasi-medical and folk traditional healing practices. Moreover, the university study of medicine rooted in classical theories of the four humors remained a medical authority, and one which generally held the approval of the church authorities and royal authorities alike. It is worth acknowledging that none of these authorities appear entirely “correct” by modern medical standards, and even the most learned methods involved practices that were toxic and harmful to the body.

Still, while some medieval and early modern medical practices were undeniably ineffective or even counterproductive, it’s worth pointing out that some practices were helpful, such as quarantine measures during plague. Even the spooky plague doctor outfits from the early modern era—equipped with cloth masks and a leather suit for personal protection—reveal growing awareness with respect to contagion by contact (prior to germ theory), which overlapped with conventional medical theories that alleged the classical notion of miasma or “bad air” was polluting infected spaces with plague and pestilence.

Mark Earnest contends that “Despite its fearsome appearance, the plague doctor’s costume—the ‘personal protective equipment’ of the Middle Ages—had a noble purpose. It was intended to enable physicians to safely care for patients during the Black Death” (“On Becoming a Plague Doctor“). The plague doctors‘ cloth beak contained perfumed herbs to purify the miasma, their waxed robe were designed to shield the practitioner, and their cane allowed physicians a quick means by which to measure their proximity and maintain distance from sick patients during examinations and treatments. Although Earnest seems to regard plague doctors as a medieval phenomenon, historical evidence suggests that these practitioners were primarily a fixture of the early modern period.

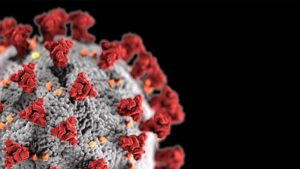

Although there is ample evidence for widespread medieval belief in learned scientia “science” (often knowledge from classical sources or universities), many historians maintain the narrative that since the scientific revolution in the early modern era, there has been a gradual trend toward belief in science and medical professionals, and the public has generally come to accept doctors’ advice over the opinions of political leaders, when it comes to issues of health and medicine. However, even if one were to accept this notion of historical progress, today’s pandemic problematizes this grand narrative by demonstrating how similar medieval and modern people can be. Like so many established institutions and professional authorities in the age of (dis)information and the rise of Trumpism in America, medical professionals are under attack, and their recommendations and expert advice have become limited by the president of the United States.

As during some medieval and early modern monarchies, it seems that the political leader of the United States feels his position entitles him to an opinion on everything and bestows him with innate wisdom. And, like the royal touch, Trump is not afraid to offer his own unconventional and unsubstantiated remedies for the novel coronavirus which has resulted in an unprecedented global pandemic during his presidency. Despite no medical training or credentials, Trump has publicly sparred with NIAID (National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Disease) Director, Dr. Fauci, and with his own CDC (Center for Disease Control) guidelines and recommendations. The use of personal protective equipment (PPE), known to slow the spread of this highly contagious and robust virus, has become politicized in the president’s attempt to deny the issue and deflect blame and responsibility by minimizing the perceived impact and threat of the disease.

Indeed, our modern pandemic is not without its scapegoats, as president Trump continues to refer to the coronavirus as the “China virus” in a racially-loaded reference to the place of the virus’ origin in Wuhan, China (briefly referenced in my recent blog on internet trolling). Additionally, calling the coronavirus the “Chinese” or “Wuhan virus” fuels conspiracies theories, including that the virus was engineered in a lab in Wuhan. In addition to xenophobic scapegoating, today’s imaginative responses include now-discredited virologist Judy Mikovits, who asserts that the novel coronavirus is being wrongly blamed for many death and even implicates Fauci in a “plandemic” that alleges masks “activate” the virus.

There is no evidence for viral engineering, nor any “plandemic” orchestrated by Fauci, but nevertheless these modern conspiracy theories persists online and ultimately in the minds of those persuaded by their unsubstantiated claims.

Trump has himself given a couple of jaw-dropping recommendations, the first being his personal endorsement of the use of untested malaria drug hydroxychloroquin in treating the symptoms of covid-19, which Dr. Fauci repeatedly cautioned Americans against taking unless recommended by medical professionals. Some have raised the issue of Trump’s own small investment in hydroxychloroquin and allege a financial conflict of interest may lay behind his endorsement of the drug, though this claim has been widely discredited. Still, despite clear evidence to the contrary, Trump continues to insist on using this drug as a treatment for the novel coronavirus.

The president’s second and more startling suggestion was that perhaps an “inside injection” of disinfectants, such as Lysol and other Bleach products, directly into the body might do the trick, considering these chemical we so effective at killing the virus (and also people who ingest them). Trump then pointed to his head, adding: “I’m not a doctor. But I’m, like, a person that has a good you-know-what.” As expected, the CDC and Poison Control (as well as manufacturers and eventually social media platforms) responded by contradicting the president’s objectively harmful recommendation, enthusiastically pushed by some of his more ardent supporters.

Even some at the conservative media outlet Fox News, often friendly to Trump and his agenda, in this instance challenged the president’s uninformed suggestion. Fox Business Network’s Neil Cavuto described Trump’s recommendations as “unsettling,” and the news anchor plainly acknowledged that “The president was not joking in his remarks yesterday when he discussed injecting people with disinfectant.” Cavuto also delivered a sober warning to his viewers: “From a lot of medical people with whom I chat, that was a dangerous, crossing-the-line kind of signal that worried them because people could die as a result.”

Indeed, when viewed in this light, Trump’s continued magical thinking with respect to covid-19 seems to mirror medieval responses to plague and the Black Death in certain ways, especially in the tendency to reach for unconventional remedies, from often unqualified authorities, in the search for a cure. But, as president Trump explains, if you’ve got the virus, already: “what do you have to lose?”

Richard Fahey

PhD in English (2020)

Selected Bibliography

Aberth, John. The Black Death. Palgrave, 2005.

Barzilay, Tzafrir. “Early Accusations of Well Poisoning against Jews: Medieval Reality or Historiographical Fiction?” Medieval Encounters 22 (2016): 517–539.

Brittain, C. Dale. “The Royal Touch.” Life in the Middle Ages, 2016.

Clark, Dartunorro. “Trump Suggests ‘Injection’ of Disinfectant to Beat Coronavirus and ‘Clean’ the Lungs.” NBC News (2020).

Cohn, Samuel K. “The Black Death and the Burning of Jews.” Past & Present 196.1 (2007): 3–36.

Durkee, Alison. “Nearly A Third of Americans Believe Covid-19 Death Toll Conspiracy Theory.” Forbes (2020).

Earnest, Mark. “On Becoming a Plague Doctor.” The New England Journal of Medicine (2020).

Enserink, Martin and Jon Cohen. “Fact-checking Judy Mikovits, the Controversial Virologist Attacking Anthony Fauci in a Viral Conspiracy Video.” Science Magazine (2020).

Hays, J. N. The Burden of Disease: Epidemics and Human Response in Western History. Rutgers University Press, 2009.

Hetherington, Marc and Jonathan M. Ladd. “Destroying Trust in the Media, Science, and Government Has Left America Vulnerable to Disaster.” Brookings (2020).

Jenkins, Catherine. “Curing Venice’s Plagues: Pharmacology and Witchcraft.” Postmedieval: A Journal of Medieval Cultural Studies 8 (2017): 202-08.

Kickhefer, Richard. European Witch Trials: Their Foundations in Popular and Learned Culture, 1300-1500. Routledge, 1976.

—. Magic in the Middle Ages. Cambridge University Press, 1989.

Levack, Brian. The Witch Hunt in Early Modern Europe. Routledge, 2016.

Mark, Joshua J. “Medieval Cures for the Black Death.” Ancient History Encyclopedia, 2020.

Murphy, Mike. “Trump Again Touts Unproven Drug to Treat Coronavirus: ‘What Do You Have to Lose?'” MarketWatch (2020).

Murray, J., H. Rieder, and A Finley-Croswhite. “The King’s Evil and the Royal Touch: The Medical History of Scrofula.” The International Journal of Tuberculosis and Lung Disease (2016).

Medieval Medicine: Astrological ‘Bat Books’ That Told Doctors When to Treat Patients.” The Conversation (2019).

Thompson, Helen . “How Witches’ Brews Helped Bring Modern Drugs to Market.” Smithsonian Magazine (2014).