Many readers of this blog will know that Notre Dame’s Rare Books and Special Collections Department in Hesburgh Library boasts a large—and growing!—collection of medieval manuscripts. Perhaps less known is a manuscript collection of a different sort, housed in the Medieval Institute on the seventh floor of Hesburgh. I am referring to Notre Dame’s Biblioteca Ambrosiana Collection, which contains over 10,000 microfilms of manuscripts held in one of the world’s great libraries, the Veneranda Biblioteca Ambrosiana in Milan, Italy. In partnership with Notre Dame, the Ambrosiana recently launched an initiative to digitize its manuscripts and make them freely available to all on the web. The first fruits of this effort can already be enjoyed: at the time of writing 382 manuscripts are viewable online. For now, though, the Medieval Institute remains the only place to access many of the Ambrosiana’s treasures outside of Milan. In celebration of the Ambrosiana, its new digital library, and the unique microfilm collection at Notre Dame, this post will briefly trace the history of the library of the northern Italian monastery of Bobbio, whose early medieval manuscripts make up one of the most important components of the Ambrosiana’s holdings.

The monastery of Bobbio was founded c. 613 by the Irish monk Columbanus with the support of the Lombard king Agilulf, who richly endowed it. In the centuries that followed its foundation, the monastery amassed one of early medieval Europe’s largest libraries, both by acquiring manuscripts from elsewhere and by producing them in its own scriptorium. Among Bobbio’s oldest and most well-known codices are its palimpsests—manuscripts in which the original text has been scraped away and then written over—including four in which the lower (i.e., erased) text is in the Gothic language.

Beyond the surviving books themselves, a valuable indicator of the scale and scope of Bobbio’s early medieval library comes down to us in the form of an inventory, made probably in the late ninth or in the tenth century. The original document has been lost, but the great Italian historian Ludovico Muratori obtained and published a fragmentary transcription of it in the eighteenth century. Even in its incomplete state, this inventory lists 666 items in the monastery’s library. (It was also in a Bobbio manuscript that Muratori discovered the so-called “Muratorian fragment,” the earliest known list of the books of the New Testament.)

The monastery suffered a decline in the Later Middle Ages; at one point, in 1346, only four monks and the abbot remained. The fate of its great library reflected this decline. When another inventory of the library was made in the mid-fifteenth century, it found only 243 manuscripts. An annotation in one surviving codex suggests that the monastery may have resorted to pawning some of its books. In 1493, a scholar working for Ludovico Sforza, the duke of Milan, noticed the library’s still ample collection of classical texts. After this discovery, many books left the monastery in the hands of humanist scholars. While some of these manuscripts have since been identified in libraries elsewhere, many others have been lost.

Two large transfers of books out of Bobbio in the early seventeenth century have, fortunately, survived nearly intact. In 1606, Cardinal Federico Borromeo, the archbishop of Milan, requested and obtained 77 manuscripts from the monastery, in exchange for which he seems to have offered the monastery printed books. These manuscripts entered the Biblioteca Ambrosiana, founded by Borromeo in 1607 and formally opened in 1609, where they remain today. In 1618, at the request of Pope Paul V the monastery donated a further 29 of its manuscripts to the Vatican Library (one of these codices went missing in the eighteenth century). At some point in the early seventeenth century at least five of Bobbio’s manuscripts also found their way into the court library of the dukes of Savoy in Turin; the total number is unknown since some others may have been destroyed by a fire there in 1667. The great French scholar Jean Mabillon visited Bobbio in 1686 and had two of its manuscripts (including the famous “Bobbio Missal” of Merovingian origin) transferred to Saint-Germain-des-Prés; both are now in the Bibliothèque nationale de France in Paris.

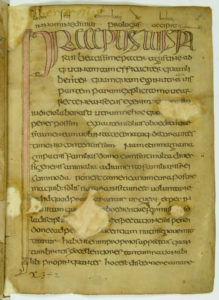

at Bobbio. Milan, Biblioteca Ambrosiana, D. 23. sup.

Note the Bobbio “ex libris” annotation (“Liber sancti columbani de bobio”) at the top of the page, added in the fifteenth century. Photo: Wikimedia Commons

By 1720, when another inventory of Bobbio’s library was made, only 122 codices remained there. Following the suppression of the monastery by Napoleon, Bobbio’s remaining books were sold at auction in 1803. As it happened, this last cache of books from Columbanus’s monastery was bought by an Irish-born doctor residing in Italy, Odoardo Raymond Buthler. After Buthler’s death the codices entered the Biblioteca nazionale universitaria in Turin. In 1904 a fire destroyed a large portion of this library’s holdings, including some of its Bobbiese manuscripts.

As a result of this tortuous history, many of Bobbio’s manuscripts have disappeared entirely, and those that remain are scattered in libraries across Europe, from Naples to Cambridge and from Vienna to El Escorial. The vast majority, however, can now be found in three repositories: the Biblioteca nazionale universitaria in Turin, the Vatican Library, and the Biblioteca Ambrosiana in Milan.

In a future post, we’ll look in a bit more detail a few of Bobbio’s early medieval manuscripts, and at the process that brought many of them—in microform—to the United States and to Notre Dame.

Michael W. Heil

2020–21 A.W. Mellon Postdoctoral Fellow in Medieval Studies at the Medieval Institute

Ph.D. in History (2013)

The University of Arkansas at Little Rock

Further Reading:

On Bobbio and its library, with references to further literature, see Alessandro Zironi, Il monastero longobardo di Bobbio: crocevia di uomini, manoscritti e culture (Spoleto, 2004); Leandra Scappaticci, Codici e liturgia a Bobbio: testi, musica e scrittura (secoli X ex.-XII) (Vatican City, 2008). In English see Michael Richter, Bobbio in the Early Middle Ages (Dublin, 2008).