A small previously unknown panel painting, Peasants At Day’s End, named for the sunset motif that forms part of its setting, is typical of 16th and 17th c. Early Netherlandish Genre Painting influenced by the pictorial language and style of Pieter Bruegel the Elder. Active in the 1550s and 60s, Bruegel worked in several media, but he is acclaimed for being among the first to paint scenes of everyday life, notably landscapes and the peasant class in a secular context. The popularity of Bruegel in his own lifetime was great, but the fervor for collecting his works after his untimely death in 1569 precipitated an art market in Antwerp and the Southern Netherlands at the end of the 16th and in the first third of the 17th c. in which copies, pastiches, and even forgeries circulated; many bore the name, Bruegel, though more often as a way of honoring the master than as a deliberate deception.[1] It might be tempting to relegate Peasants At Day’s End to the efforts of an ardent follower or forger, but a signature recently found in an unusual location, together with its comparison to a landscape by Bruegel The Elder, have prompted the question of whether the painting may be by Pieter Bruegel the Elder himself. [2]

The pocketsize picture, in many ways reminiscent of a late medieval miniature, measures a scant 5.5 x 7.75 inches. It appears to be oil on oak panel and is darkened due to grime and old varnish. Gilding is visible in places beneath flaking varnish on the frame. Both the cradling of the wooden support—a popular 19th c. conservation practice—and the once-gold frame suggest the painting held value for past owners, although owing to its lack of provenance and believed lack of a signature, it was assumed to have little more than aesthetic value.

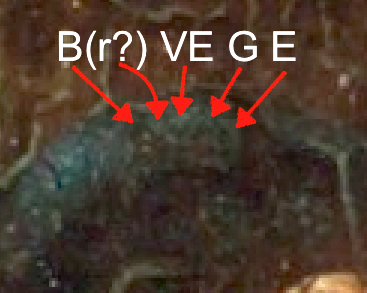

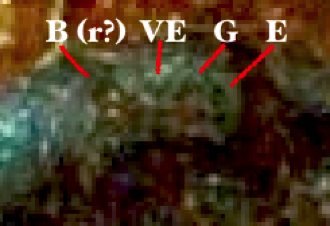

Examined for the first time using high-resolution photography, the painting was discovered to have a signature that is, for all practical purposes, much too small to have been of use to a 16th or 17th c. forger. In addition to creating a signature large enough to easily see, such a forger would surely have (1) placed it in an expected location and (2) borrowed a more complete form of Bruegel’s signature. The extant signature appears somewhat abbreviated, which is the case with a handful of Bruegel the Elder’s known signatures. That it is found on the hat brim of the walking figure is unusual and yet intentional to the whole artistic plan as we will see further below. Barely detectable by zooming in on the highest resolution photo (Figure 3 and Figure 4) the signature appears to read, B, followed by an unclear letter or mark, then VE (in ligature, unusually with V above E), G, and perhaps another E: “B(?)VEGE”. Bruegel is known to have signed works, BRVEGEL, sometimes with the VE in ligature, albeit side-by-side in the usual manner, but his signature is also known to vary significantly. In early drawings he signed in lower case letters, sometimes, brueghel, sometimes with a circumflex above “u”. Later he dropped the “h” and, on both drawings and paintings, began to use roman capitals. On The Temptation of St. Anthony (1556), he unusually signed, Brueggel. On Head of a Peasant Woman (1568), only “Pb” was uncovered in 2018 on the top right corner. [3] On The Drunkard Pushed Into The Pigsty (1557), a microscopic signature was found on the pigsty, BRVEG, with the VE in ligature and EL missing. [4] On Winter Landscape with Bird Trap (1565), x-radiography revealed an abbreviated signature beneath a later more complete signature; the hidden, first signature, reads only, BVG. [5] On The Fall of the Magician Hermogenes (1564), Bruegel mistakenly inverted the order of two roman numerals in the date. [6] On Peasants At Day’s End, what appears to be an unusual form of ligature with V placed above E might be explained by similar absentmindedness (forgetting the V in the first instance), or by the need to conserve space by further abbreviating his signature as he did elsewhere. Bruegel often dated his works variously using either arabic or roman numerals. So far, no date has been found on Peasants At Day’s End.

Due to its very small format, Peasants At Day’s End should perhaps not be expected to offer the same scope for detail and brushwork as Bruegel’s larger works. Cleaning may uncover more distinctive features, and yet some incredible attention to detail, such as fingernails painted on the tiny hands of the figures, are already discernable. [7] We are also reminded that not all of his paintings were painted to the same standard. The Drunkard Pushed Into The Pigsty (1557, private collection), a small wooden plate attributed in 2000, was at first disputed even after a signature was found. It is now considered one of his two earliest paintings, though not as expertly painted as later masterpieces. It measures a comparable 20 cm (7.8”) in diameter. Early Netherlandish art historian and curator, Manfred Sellink, says the pigsty roundel “betrays his lack of experience as a painter,” and art historians, Christina Currie and Dominique Allart, tell us “it is likely that Bruegel produced paintings from the very beginning of his career, even if the earliest surviving works do not date from before 1557,” pointing to the likelihood that there once existed other less masterful paintings. [8] This leaves us with the possibility that there are more to be uncovered. Bruegel had early training as a miniaturist. [9] Several small-format works by him survive and others, now lost, are noted in historical inventories; some are neither described nor named. [10]

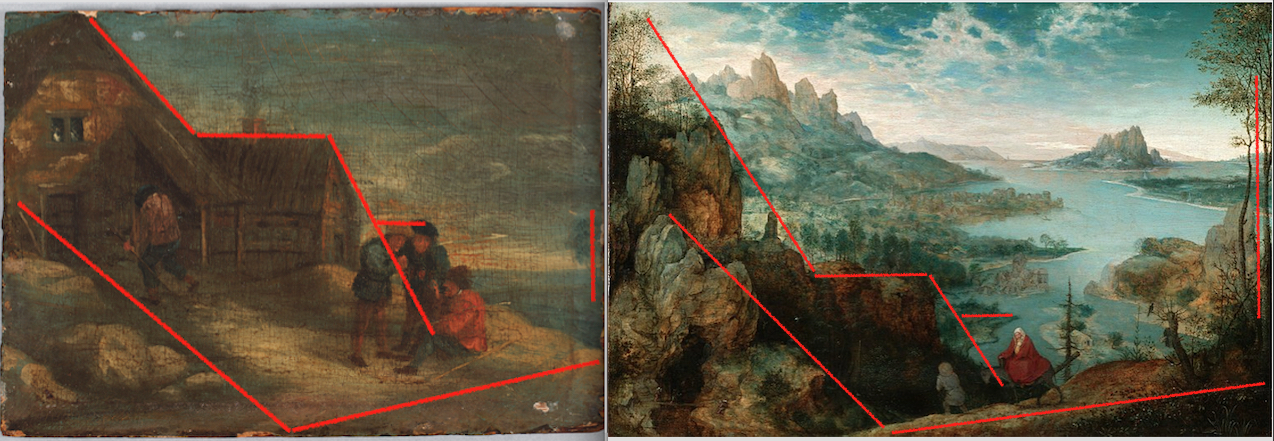

Sellink mentions Bruegel’s use and reuse of compositional types, schemes and motifs as well as his reuse of individual figures throughout his career and in different media. Also considered a small panel, Bruegel’s Landscape With The Flight Into Egypt (1563) is nearly three times the dimensions of Peasants at Day’s End, yet the repeated arrangement of the two compositions is unmistakable. Sellink used The Flight Into Egypt as a case in point to illustrate Bruegel’s repetition of compositional schemes, comparing some of its features to his pen and ink drawing, Mountain Landscape with River and Travellers (1553, The British Museum) [11], but Peasants At Day’s End offers points of comparison that are even more closely related (Figure 5).

The mass of darker rocks in The Flight Into Egypt can be compared to the mass of dark buildings in Peasants At Day’s End. The lines pointing us to the Virgin in The Flight Into Egypt, point instead to the sitting figure; each wear red and anchor their respective compositions. Each are also similarly framed above-left and below by smaller dark shapes. There is a line of lighter rocks (bottom left quadrant) that runs roughly parallel to the more central diagonal line, and in each painting, both the tree on the right (in each the foliage begins just above the horizon, a similarly shaped swath of horizontal blue beneath) and the darker triangle across the bottom right corner, serve to keep the eye in the picture: Bruegel’s use of the tree in repoussoir is traditional. [12] The chimney and smoke in Day’s End appears to have the same compositional function as the prominent mountain peak with the vertical cloud formation directly above it; it is surprisingly chimney-like as well, and is found in the upper left quadrant of Flight into Egypt; it is a visual extension of a darker chimney-shaped rock further below it. The warm glow on the patch of rocks (middle far left) in Flight Into Egypt can be compared to the warm glow on the upper facade of the house in Day’s End, which approaches a trapezoidal shape. Though they are faded or obstructed by the dirty condition of the panel, what appear to be clouds in the background of Peasants at Day’s End (grayer and to the right) are separated from a bluer sky (left) by the line of the cloud formation which trails back and forth in a wide zigzag, similar to the lines of the distant landscape in Landscape With The Flight Into Egypt. The zigzag of the middle distance in each also leads the eye to the anchor figure in red. In addition to these, one of the most compelling comparisons is the walking figure. Instead of Joseph, whose turned back leads us toward a dark grotto, our walker in Day’s End leads us toward the dark house. Each is partially framed within a darker triangle, the right side of which echoes the angle of the back and helps to accentuate the leaning, active posture. It adds to the illusion of psychological and physical fatigue carried “on the back” of each tired figure in their respective narratives, and at the same time provides a visual push forward. The left side of the triangle is the line at which the front edge of the hat and knee line up. The contextual similarity of the two walking figures is extraordinary, and is characteristic of Bruegel. An example of his use of the triangular or lean-to effect can also be seen in The Conversion of Saul (1567), where a much larger scale figure is similarly framed by a darker partial triangle formed by the rock behind and above; the line of the rock echoes the line of the back and leg and similarly helps to push the figure along visually (Figure 6 left). The same effect can be seen in Parable of the Blind (1568), where the last two figures in a line of stumbling blind men are visually pushed by the angle of the triangles above and behind them (Figure 6 right). In their case the triangles push forward, but also backward again (the darker plane of each), adding to the illusion of motion, but also of hesitation—to the topsy-turvy, precarious balance of the two who are doomed to fall like those leading them.

The schemes of the two compositions being compared, Landscape with the Flight into Egypt, and Peasants At Day’s End are so closely related that it is difficult to imagine one being produced without direct knowledge of or access to the other, and there is no evidence that Bruegel had a large workshop or apprentices—he worked alone. [13] We know that Pieter Brueghel the Younger carefully copied some of his father’s works after his death; he did not have direct access to most of them, and likely based several of his reproductions on a store of drawings and cartoons preserved by the family along with explicit instructions for close replication. [14] In our case, the two compositional schemes are astoundingly similar, but the theme and subject matter of each is very different; if one informed the other it didn’t preclude the free creative process of an artist whose intent was not simply to copy a painting. The comparison speaks to the practice of an artist who is known to have borrowed from an arsenal of his own compositional schemes, motifs, and figure types in creation of uniquely different works—Bruegel the Elder. Because Peasants At Days End has not yet been dated, we should not assume which of the two came first.

Peasants At Day’s End engages the classical, end-of-day motif that represents the waning of a full life lived—the reason for its title. The older men grouped at the focal center of the composition in the sunset of their years are literally highlighted by the setting sun, which also casts long shadows and glows warmly on the facades of the rural architecture behind them. In this way, nature and the cycle of life become an important part of the compositional setting married to the narrative. The fact that it is day’s end is further emphasized by the plodding figure returning home. The composition is built on a series of triangular planes (echoes of the rooflines) that zigzag across the entire picture. We are drawn in by the sitting figure in red. The eye then follows his raised hand that sends us directly to the face of the middle figure, which stares straight out of the picture, fully engaging the viewer by making eye contact. From the group of three, a pathway of light leads the eye to the walking figure, to the reflection of light on his back, and to a brighter spot of light on his collar that serves as a proverbial “x marks the spot,” because it underscores where we find the signature on the more subtly lighted hat brim. How the eye ends up at this location depends on the viewer’s full investment in the picture narrative and willingness to be led by the artist. We understand that if the walking figure looks up or changes direction, the signature will disappear. We see it only in a peek-a-boo moment as the walker, with his bobbing hat, is focused on the ground ahead, and we smile when we realize the artist is having some fun with us; finding the cleverly placed signature is our reward for playing along.

The signature is so small it is fated to go undetected unless we follow the clues—follow the light, as it were—and even then, we are able to read it only with the help of magnification. The viewer is fully engaged and thoroughly entertained by the discovery. In addition to the extremely small size of the signature, its unusual location, and abbreviated form, a forger would also be less likely to employ as much creative freedom and compositional intentionality in the placement of the signature as would Pieter Bruegel the Elder himself. Scholars repeatedly speak of Bruegel’s humor and sharp wit. We know he based many of his works on proverbial sayings as well as biblical and classical mythology. A well-known classical metaphor for old age—the end of the day—is part of the setting of Peasants At Days End. How the little painting rather astoundingly mirrors the scheme of one of Bruegel’s landscapes and other points of comparison that speak to the painterly practice, but also the spirit of Pieter Bruegel the Elder, warrant further investigation. Continued research of the previously unknown genre painting is pending further imaging and technical analysis.

Heather A. Reid, PhD

[1] Christina Currie and Dominique Allart, The Brueg[H]el Phenomenon: Paintings by Pieter Bruegel the Elderand Pieter Brueghel the Younger with Special Focus on Technique and Copying Practice, Vol. I (Brussels: Royal Institute for Cultural Heritage, 2012) 29, and on artistic works by others that bear the name Breugel, 45-46; on which also see Larry Silver, “The Importance of Being Bruegel: The Posthumous Survival of the Art of Pieter Bruegel the Elder,” in Pieter Bruegel the Elder Drawings and Prints, ed. Nadine M. Orenstein (New York: The Metropolitan Museum of Art, and New Haven and London: Yale University Press, 2001) 67. According to both of these sources, Jacob Savery is the only known deliberate forger of Bruegel the Elder’s works.

[2] I am very grateful for the insight and suggestions of medieval art specialist, Dr. Maidie Hilmo, Victoria, Canada, who read early versions of this essay.

[3] Elke Oberthaler, Sabine Pénot, Manfred Sellink, and Ron Spronk, Bruegel: The Master (London: Thames & Hudson, 2018) 272, item 82.

[4] Roger van Schoute and Hélène Verougstraete, “A Painted Wooden Roundel by Pieter Bruegel the Elder,” The Burlington Magazine 142:1164 (March 2000): 140-46, esp. 140-41, and Oberthaler, Pénot, Sellink, and Spronk, 73.

[5] Currie and Allart, 184.

[6] Currie and Allart, 74. On Bruegel the Elder’s signature, including inconsistencies, 73-79, and van Schoute and Verougstraete, 144-45.

[7] Other details are observable to varying degrees prior to the cleaning of the panel, but their discussion in the present article is prohibitive for reasons of space. In addition to fingernail details, of note are the other figure types (comparable to types Bruegel the Elder reused), architectural features such as the paned glass, thatched roofing and chimney, what appears to be the tail end of a ribbon-like banner flying from the upper story of the house (visible only over the sky portion beyond the roofline so far), what appears to be a nearly microscopic dog and copper pan on the extreme left margin, doorway hinges and entry hardware, as well as an axe leaning near the entry, and three hoes the walking figure is carrying.

[8] Oberthaler, Pénot, Sellink, and Spronk, 73. Currie and Allart, 38. Sellink also tells us, Bruegel “trained, and started his career, as a painter” before turning his attention to working as a draughtsman and designer of compositions to be engraved. See his, “Leading the Eye and Staging the Composition: Some Remarks on Pieter Bruegel the Elder’s Compositional Techniques,” in Oberthaler, Pénot, Sellink, and Spronk, 295-313, esp. 302-303. Sellink’s essay is only found in the electronic edition accessed by using a code provided in the print edition. Although it is not known if his father, who worked alone, initiated such a practice, we know that Pieter Brueghel the Younger’s workshop catered to a mixed clientele, including those content with less premium productions (Currie and Allart, 62).

[9] Currie and Allart, “Another figure who would have had an influence on his early training was Pieter Coecke’s wife, Mayken Verhulst, herself a well-known miniaturist” (39). Pieter Coecke van Aelst (d. 1550) was Bruegel’s master and Bruegel later married their daughter. On his training as a miniaturist, likely by Verhulst, also see Sellink, “Leading the Eye,” 303.

[10] Dominique Allart, “Did Pieter Brueghel the Younger See his Father’s Paintings? Some Methodological and Critical Reflections,” in Brueghel Enterprises, ed. Peter van den Brink (Maastricht: Bonnefantenmuseum; Brussels: Musées Royaux des Beaux-Arts de Belgique; Amsterdam: Ludion Ghent, 2001) 47-57.

[11] Sellink, “Leading the Eye,” 299.

[12] Sellink, “Leading the Eye,” 301.

[13] Currie and Allart, 64.

[14] Allart, 2001, 55-56.