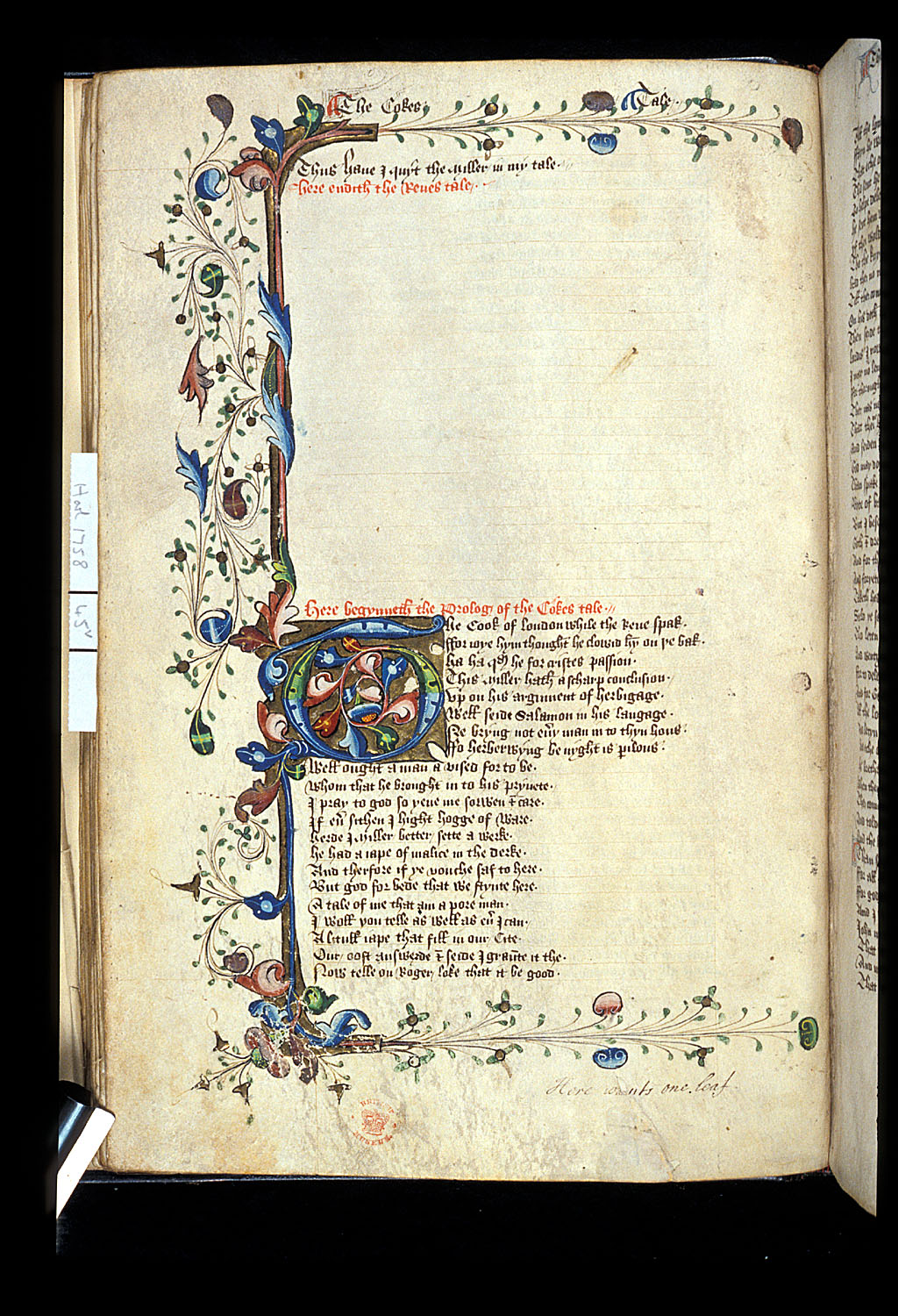

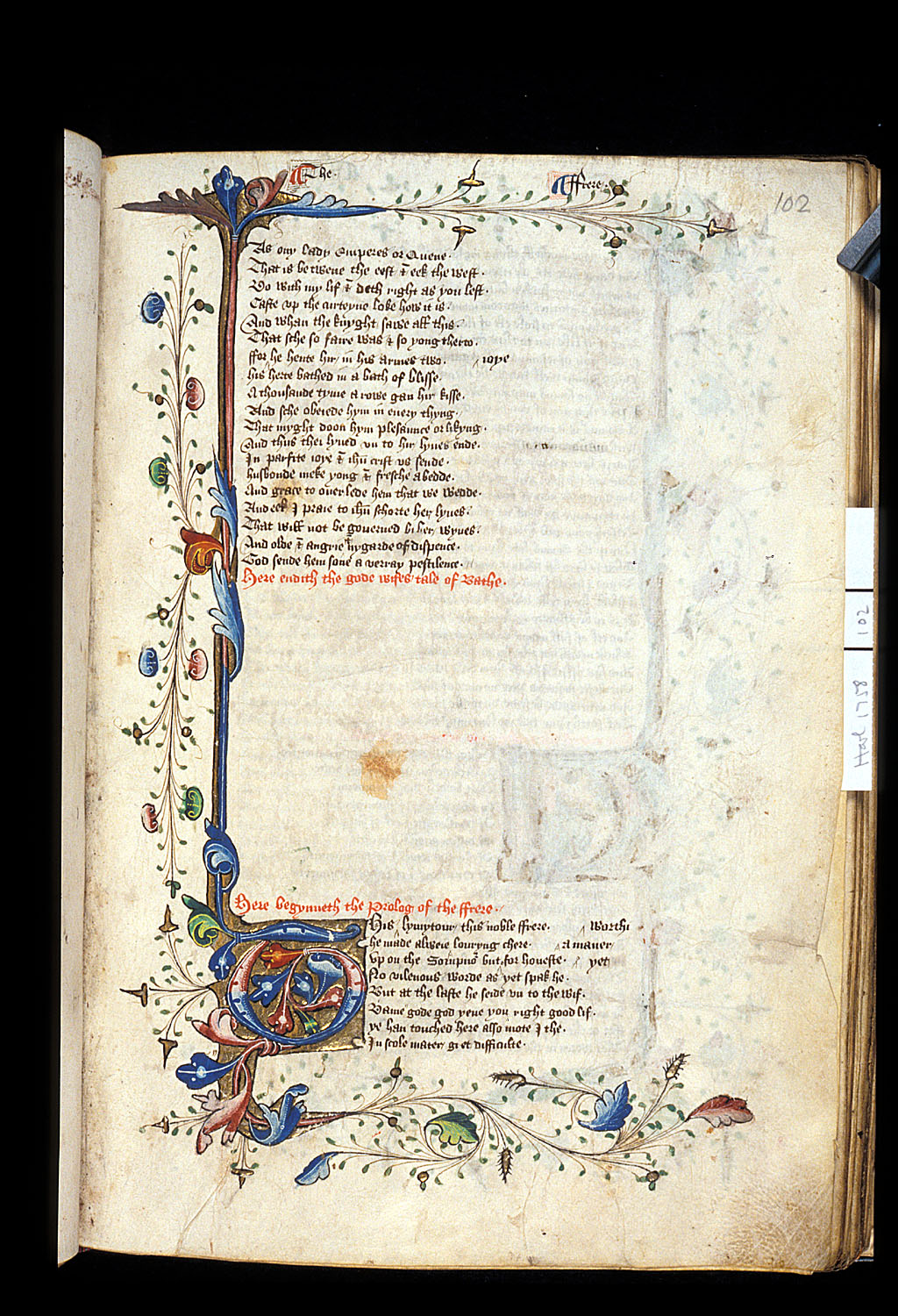

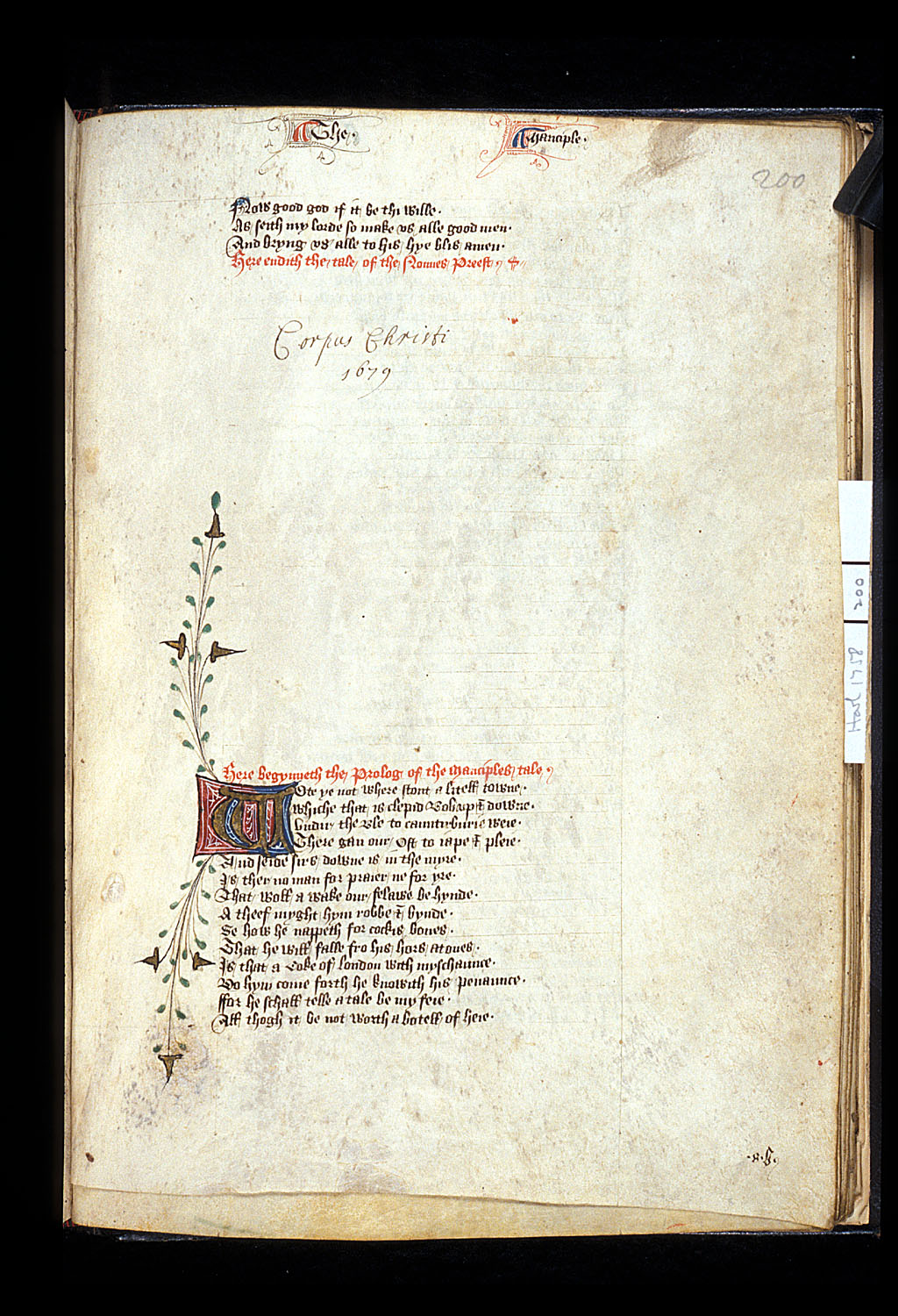

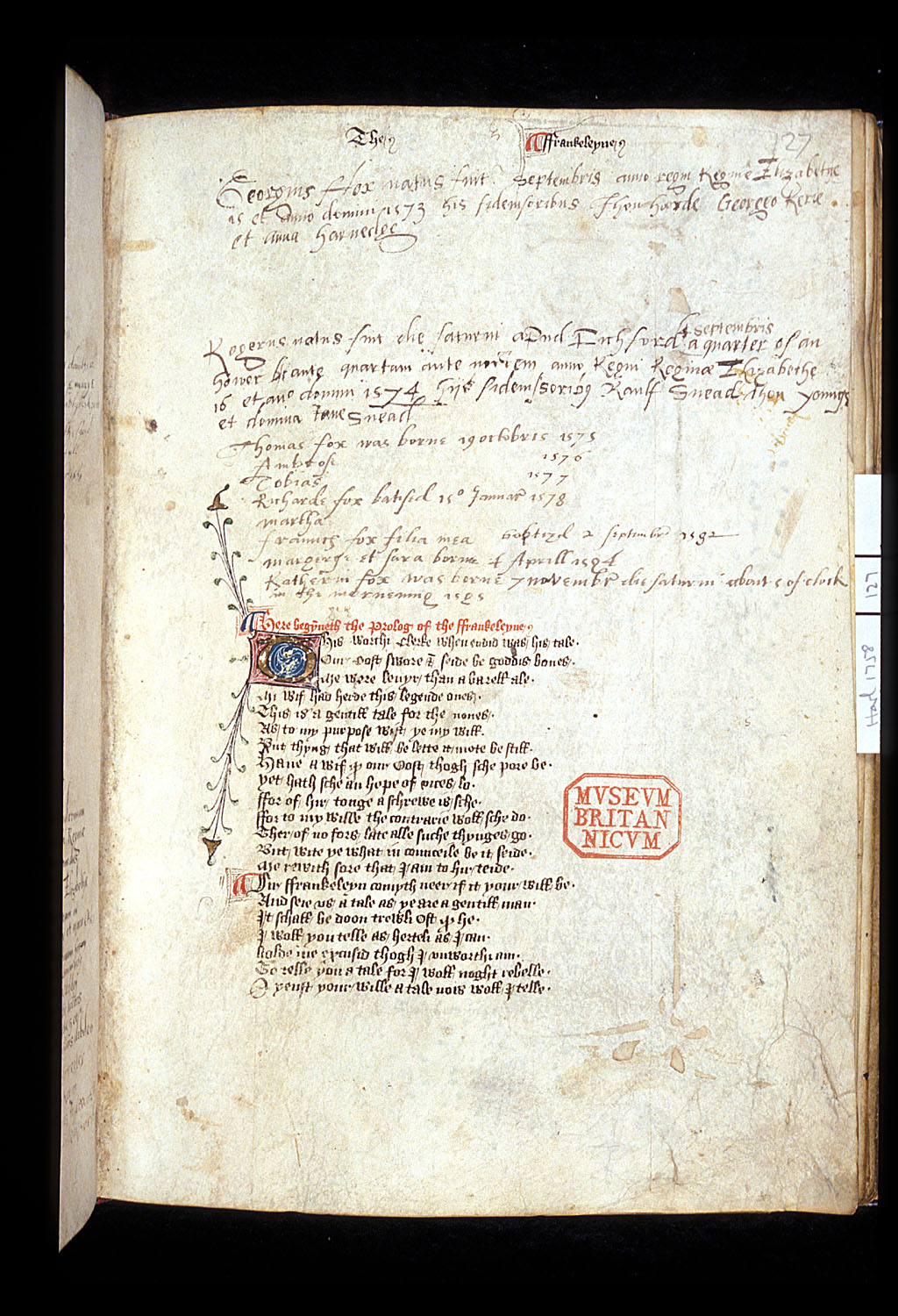

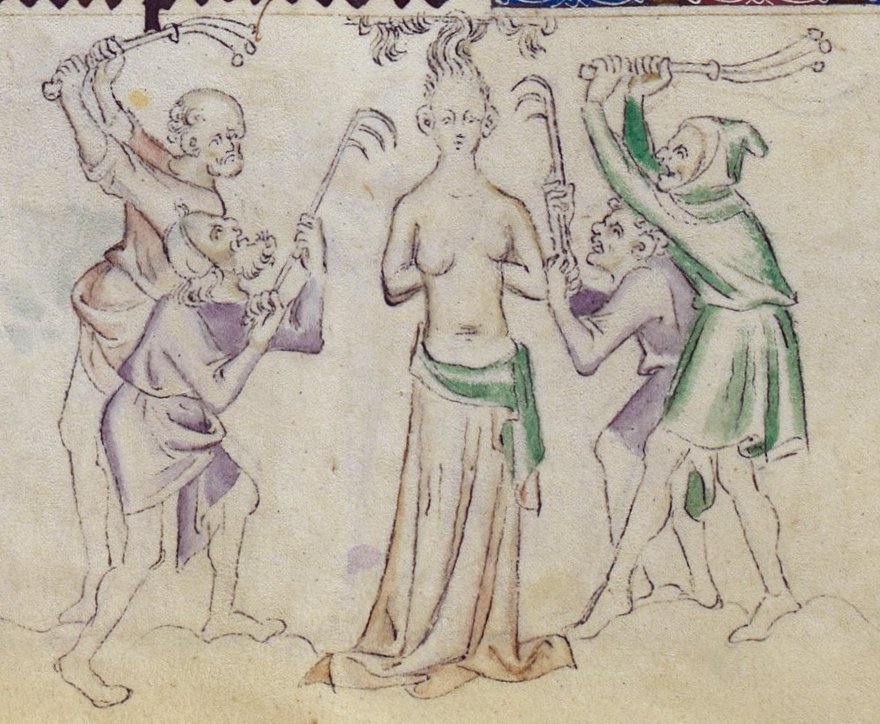

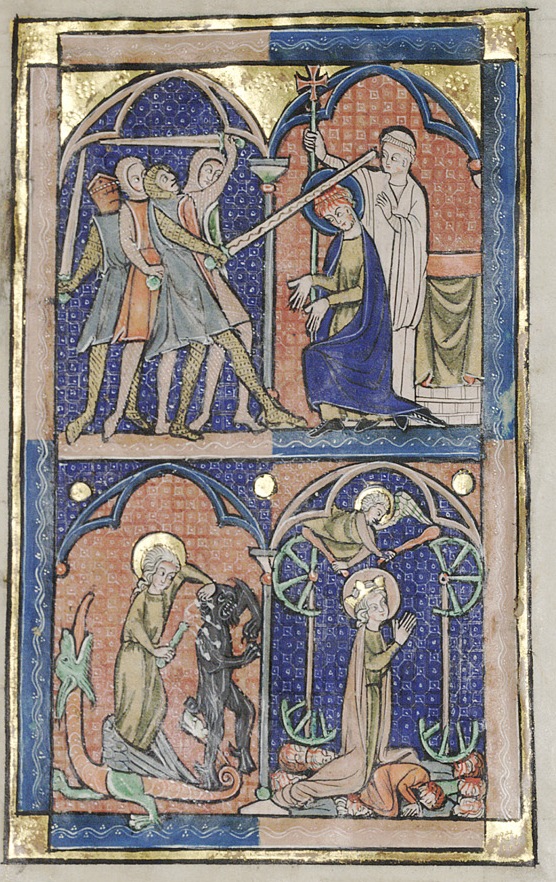

Bodleian Library MS. Douce 104, dated 1427 by the scribe, contains the only extant cycle of illustrations in a copy of Piers Plowman. The manuscript contains 72 miniatures, ranging from major characters to allegorical personifications to figures mentioned only in passing in the text of the poem. As Kathleen Scott has noted, illustrators in the fifteenth century generally worked from templates or models of figures used in other texts; because of Douce’s singularity in its extensive illustrations of the poem, we can conclude that the images in the manuscript were inspired not by commonly used models, but by the illustrator’s personal response to the text at hand. Thus, the Douce images offer modern readers a unique opportunity to understand how medieval readers (or at least professional readers, like scribes and illustrators) of Piers Plowman may have interpreted Langland’s famously complex poem–and, for the purposes of this post, the poem’s impaired sinners.

While Langland describes his Seven Deadly Sins as rather grotesquely impaired and occasionally disabled in the C-text, the Douce illustrator largely normalizes physical aberrance in his images of the Sins. When taken together, the descriptions in the poem and their accompanying images encourage an interesting relationship between sin and impairment, namely that while sin indeed results in physical impairment, the impairments are perceptible largely to the sinner him- or herself.

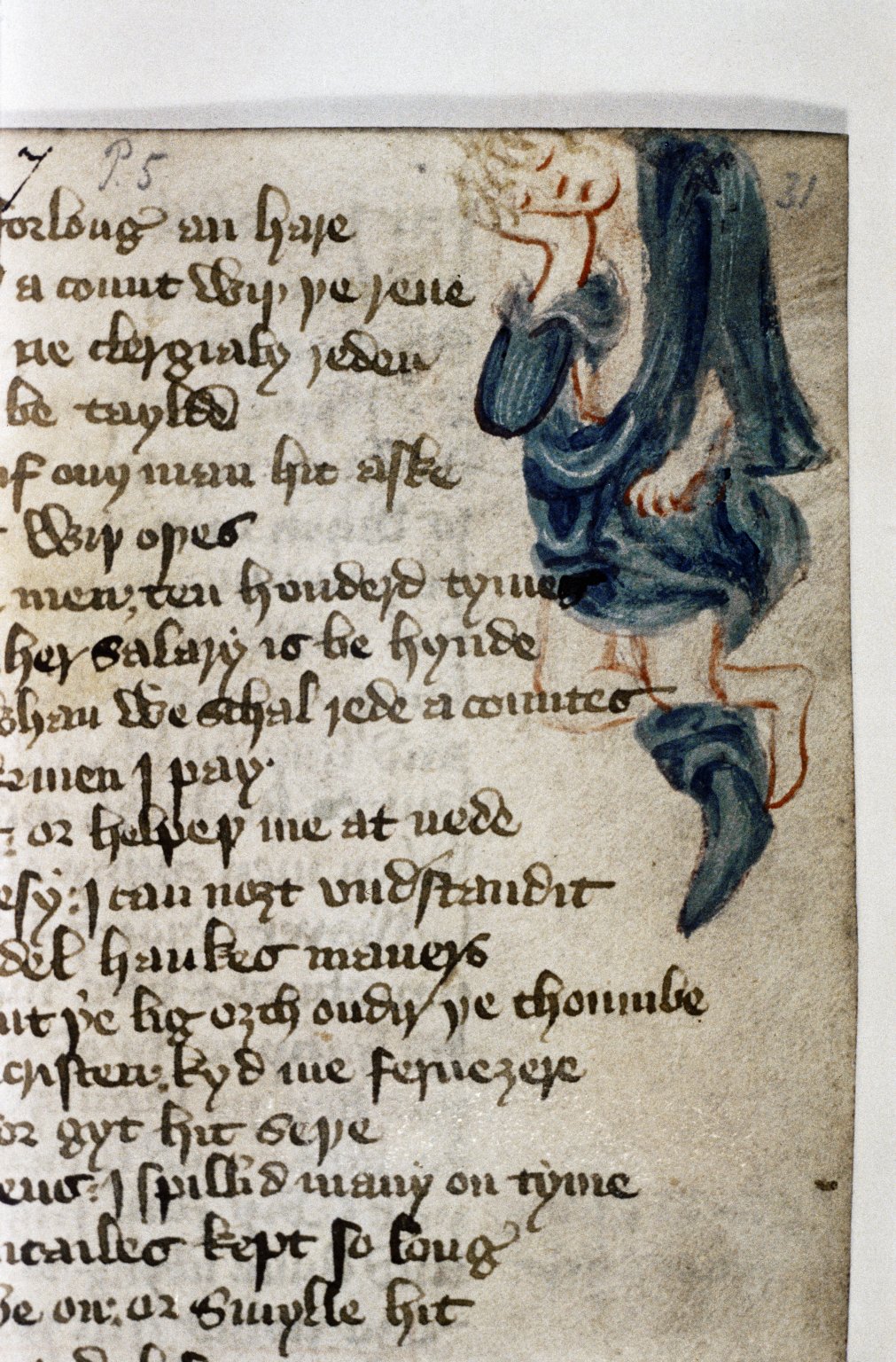

For example, in MS. Douce 104, Sloth is depicted as a young man with rumpled clothing and a boot on only one foot; the other foot remains bare and tucked up behind the booted foot in what could perhaps be a protective gesture (though it’s equally likely that he has just curled up in his sleep). Though Sloth is initially described in the poem as “byslobered with two slimed yes” (C.VII.1), the only concession the illustrator makes to any physical deformity is that single missing shoe, likely indicative of Sloth’s gout, the swelling from which would have prevented him from wearing his boot. What is most interesting here is that the illustrator’s interpretation seems to have normalized Sloth’s appearance from the description presented in the poem, in which Sloth is quite obviously impaired or even deformed.

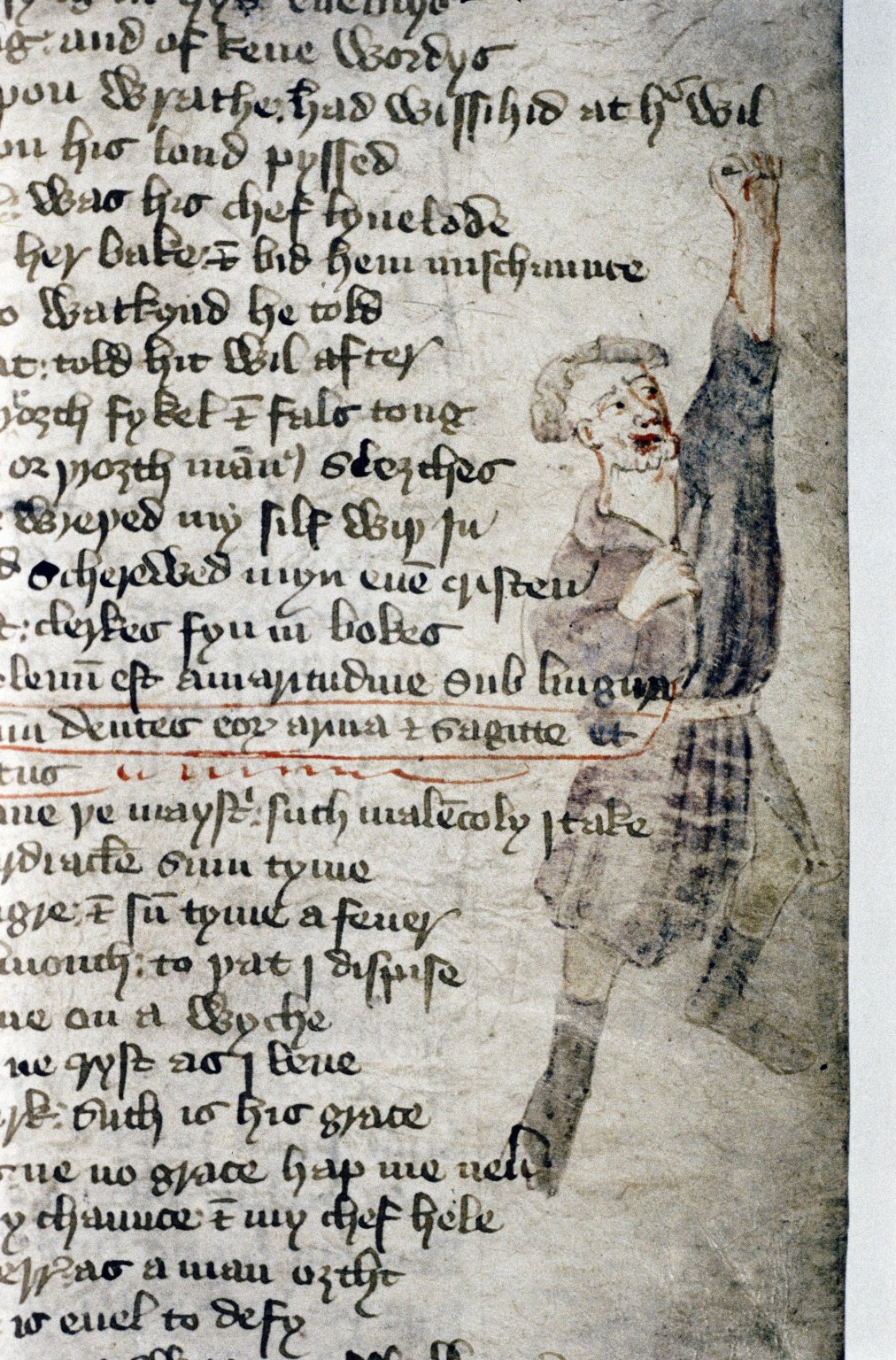

Envy provides another relevant example. In the C-text of Piers Plowman, Envy laments the physical repercussions of his sins: “no sugre ne swete thing [may] aswage my swellynge” (C.VI.88); further, he complains that he has become “so megre for Y ne may me venge” (C.VI.94). In spite of these physical descriptions, the Douce illustrator’s interpretation of Envy is in no way noticeably impaired. Envy appears in folio 25r, an adult man wearing a belted tunic and boots, his left hand raised in a fist (presumably in reference to “A wroth his fuste vppon Wrath”) while his right hand clutches his shirt. In contrast to Langland’s Envy, who describes himself as simultaneously swollen and “megre,” his stature is neither stout nor thin; he actually looks quite healthy and strong. When taken together as they appear in Douce 104, Langland’s written description and the illustrator’s image enable an interpretation of Envy’s physical ailments as discernible only to Envy himself, perhaps indicating that the consequences of sin, though physical, are felt most acutely by the sinner.

There is, of course, much more to say about sin, impairment, and disability in Piers Plowman; for the moment, though, let us revel in both the fascinating glimpse into fifteenth-century reception of the poem and the interpretive possibilities for modern readers provided by the illustrator of MS. Douce 104.

Dana Roders

PhD Candidate

Department of English

Purdue University

Further Reading

Hilmo, Maidie. “Retributive Violence and the Reformist Agenda in the Illustrated Douce 104 MS of Piers Plowman.” Fifteenth-Century Studies 23 (1997): 13-48. Print.

Kerby-Fulton, Kathryn, and Denise L. Despres. Iconography and the Professional Reader: The Politics of Book Production in the Douce Piers Plowman. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 1999. Print.

Kerby-Fulton, Kathryn, Maidie Hilmo, and Linda Olson. Opening Up Middle English Manuscripts: Literary and Visual Approaches. Ithaca: Cornell University Press, 2012. Print.

Metzler, Irina. Disability in Medieval Europe: Thinking About Physical Impairment During the High Middle Ages, c. 1100-1400. New York: Routledge, 2006.

Scott, Kathleen L. “The Illustrations of Piers Plowman in Bodleian Library MS. Douce 104.” The Yearbook of Langland Studies 4 (1990): 1-86. Print.