“That ‘Poetry is the cradle of philosophy’ is axiomatic”

(John of Salisbury, Metalogicon I.22).

It is a truth generally acknowledged that in the Middle Ages a liberal arts education consisted of the trivium (grammar, logic, and rhetoric) and the quadrivium (arithmetic, music, geometry, astronomy). Poetry –what we might call “literature”– was primarily taught by grammarians and rhetoricians in the Middle Ages. Literary scholars, like Rita Copeland and Marjorie Woods, have therefore been very motivated to study exactly what the language disciplines of Grammar and Rhetoric entailed and precisely how they were taught in order to have a better sense of what the study of literature must have looked like in this period. Their works are indispensable for the study of medieval literature and truly are the bulk of where instruction in poetics lay in the Middle Ages. And yet, once cannot stop there.

Knowing exactly where to put poetry was something that clearly bothered many medieval philosophers. While today we might assume that poetry would clearly be associated with the Trivium, or the arts dedicated to words, specifically grammar and rhetoric, certain medieval thinkers located it within logic and also the Quadrivium, or the arts of number. Understanding why can help us to understand the multi-faceted way in which the medieval mind approached poetry in particular and the literary arts more generally.

In the twelfth century when there were major curricular changes afoot in schools and universities, John of Salisbury maintained that poetry belonged to the art of grammar although it was closely allied with rhetoric. “Art,” writes John of Salisbury, “is a system that reason has devised in order to expedite, by its own short cut, our ability to do things within our natural capacities. Reason neither provides nor professes to provide the accomplishment of the impossible;” Instead, reason pursues the possible by means of an efficient plan, what the Greeks would call a methodon (Metalogicon I.11, p.33). As J.J. Murphy writes in the Cambridge History of Literary Criticism, Vol. II: The Middle Ages:

In medieval terminology the Latin word ars (plural: artes) denoted a body of principles relating to a specific activity such as painting, music, preaching, or writing. By extension the term was also used for a written treatise on the subject of a particular art […] The term ‘art’ or ars when applied to such a treatise indicates a discussion of what the ancient Greeks would have called techné ––‘technique’ or ‘craft’ –– rather than an abstract or theoretical discussion of a subject (p.42).

The practitioner of an art is therefore called an artifex or craftsman, and the study of the art consisted of both the intrinsic principles for practice and the extrinsic practice of the art itself.[1] When art is understood in this way, craftsmen generally agree that the person able to produce art is more skilled that the person skilled at conveying the principles underlying art. While poetry was clearly a craft that required a practitioner to study a method of practice, it was by no means clear where it ought to fit in the medieval curriculum of the arts.

John of Salisbury reports that some people thought poetry should be its own subject (shockingly!) because so much of it is clearly a “product of nature’s workshop” (Metalogicon I.18). The close tie between poetry and nature formed the basis of their argument, but John of Salisbury warns pragmatically that if poetry is removed from grammar, “its mother and the nurse of its study,” the study of poetry could be “dropped from the roll of liberal studies.” In other words, everyone studies grammar, which in those days often included a careful study of works like Virgil’s Aeneid. If poetry became its own subject, people might not take it at all!

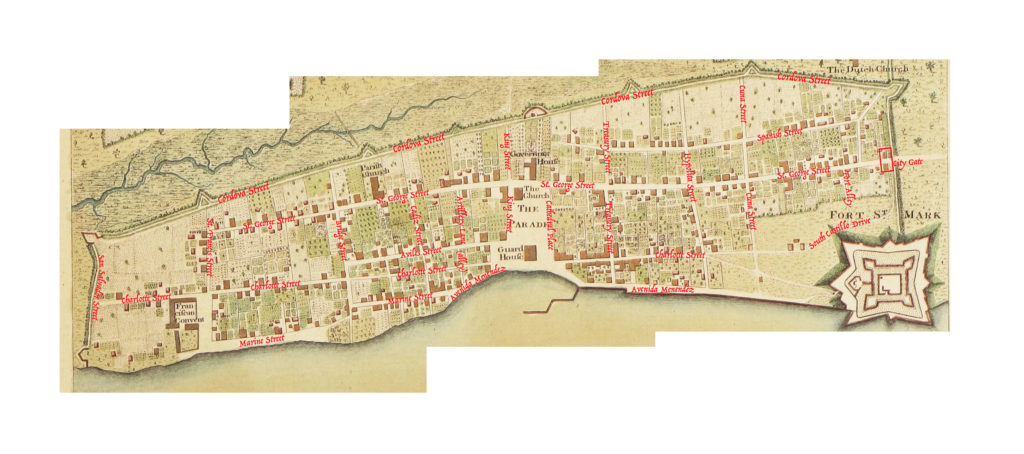

Français : Poétique (Aristote) en arabe – Abu Bishr Matta

العربية: فن الشعر لأرسطوطاليس نقل أبي بشر متى – من مخطوطة باريس ٢٣٤٦

http://gallica.bnf.fr/ark:/12148/btv1b8422956q/f273.image

Some philosophers thought that poetry actually belonged to the subject of logic. These people were especially concerned about how to classify Aristotle’s Poetics. In Ancient Greece, Aristotle had written a group of works (one might even say lecture notes) on logic when teaching at the Lyceum. His followers, the Peripatetics, classified these works as the Organon, meaning instrument or tool, because they saw them as instrumental in preparing for the study of philosophy. The Latin West had only select works from the Organon until their increased contact with Arabic philosophers like Avicenna, who wrote a commentary on the Poetics. Following the Greek commentators on Aristotle, most of the Arabic (and subsequently Latin scholastic) commentators saw Aristotle’s Rhetoric and Poetics as the seventh and eighth works of Aristotle’s Organon. In their zeal, therefore, to comment on the entirety of the Organon, some Latin scholastic commentators, like Herman the German, viewed poetics as a part of Logic.

As surprising as it might be to think that poetry should be considered primarily within the context of “logic,” there is strong evidence that poetry was also studied within the context of the quadrivium. And yet, many medieval thinkers, the Pythagorean believed that number lay at the root of creation itself. For example, Dante writes in the Convivio when commenting on the beauty of a canzone:

All of you who cannot perceive the meaning of this canzone, do not reject it on that account, but consider its beauty: considerable for the way it is constructed, which is the concern of the grammarians; the ordering of its discourse, which is the concern of the rhetoricians; and for the metrical numbering of its parts, which is the concern of poets. (II.xi.9–10)

The key word to focus upon here is numbering. Familiarity with the Commedia and its frequent references to the starsis enough to convince a reader that one aspect of the numbering that Dante had in mind was the medieval discipline of astronomy, but there is also good reason to think that Dante had music in mind. Some of this evidence is textual…the numerous references to music in the Purgatorio and Paradiso…, but some of this evidence can be found in Boethius.

The standard textbook for the teaching of music theory in the Middle Ages was Boethius’ Fundamentals of Music, and until 1255, it was not uncommon for most educated men , including Dante, who undertook a liberal arts education to have at least some instruction in the subject.[2] As a result, even 11th and 12th c. philosophers like Anselm and Peter Abelard wrote sacred poetry and song. In this book, Boethius speaks of poetry as a subset of one kind of music.

Boethius begins his work on music with a philosophical justification for its study. Citing Plato and Pythagoras, he observes that music is so deeply engrained in human nature that from a young age it has the power to move human souls, transform their character, and even affect their health and sense of well-being (I.1.180–185). He explains that this phenomenon should leave us with no doubt that “the order of our soul and body seems to be related somehow through those same ratios by which subsequent argument will demonstrate sets of pitches, suitable for melody, are joined together and united” (I.1.186). Since “music is so naturally united with us that we cannot be free from it even if we so desired,” then “the power of the intellect ought to be summoned so that this art, innate through nature, may be mastered, comprehended through knowledge” (I.187). In this way, Boethius justifies the study of music because it reflects something about the fundamental nature of the human soul.

Español: “El Rey David, la Señora Música y los músicos”. Del manuscrito “De institutione musica”. Boecio.

Date Original: 1941 – 1942. Copy upload: 2010.Source: http://images.amazon.com/images/P/B000009OM1.jpg

In this work, Boethius identifies three kinds of music––cosmic, human, and instrumental. This categorization implies that the human response to music is rooted in the nature of not only the human soul but of the cosmos (I.2). Cosmic music, or the music of the spheres, is the harmonious sound produced when the stars in their courses and the diversity of seasons move swiftly together in harmonious union (1.2.187–188). Human music does not concern the music produced by humans. Rather, it is the music found in the harmony of soul and body in a human being. Boethius describes this music as “a careful tuning of low and high pitches as though producing one consonance” (I.2.189). It unites not only the rational and animal parts of the soul, but the parts of the body and the body’s union with soul. Boethius promises to speak about this subject later, but he never returns to it. Instrumental music, for Boethius, includes the harmonious sounds produced by tension of strengths, human breath, percussion, etc. (I.2.189). This kind of music is what most people today associate with music, but Boethius’ understands this music to operate according to the same mathematical principles of both cosmic and human music. This mathematical concordance explains the reasons for music’s profound effect on the human soul.

Although the producer of cosmic and human music is ultimately God, instrumental music must be produced by a human musician. Boethius’ definition of a human musician broadens the horizon within which music itself is narrowly considered today. He identifies three classes of musician: the instrumentalist, the poet, and the rational judger of music (I.34.224).

The instrumentalist is no greater than a “slave” because one does not need the faculty of reason in order to produce music upon an instrument.

The second class of poets are presumably higher than slaves, but Boethius remarks that even the poets create songs by instinct rather than reason. One might recall here Lady Philosophy’s attack upon the Muses as “harpies” because their base songs only continued to prolong Boethius’ misery.

The third class of musician is the one with the ability to judge rhythm, melody, and composition. Since this class exercises reason in their experience of music, they alone should be considered worthy of esteem. This final judgment may seem harsh, but it was a common opinion in his day; Augustine repeats a similar idea in De musica.3 In fact, both men express their love of hearing music with some guilt, even though Augustine insists that music should remain in churches (Conf. 9.6, 14 and 10, 33, 49–50; Consol. I.2 and IV.6.6). In other words, Boethius repeats the infamous attack of Plato on the poets, even though he himself writes poetry in the Consolatio.

It is startling to consider that Boethius includes both poets and song-writers within the class of musicians. Any time a human being takes the mathematics of sound seriously in the construction of a work of verbal art, they are a musician, whether or not the words constructed are intended for accompaniment with music. Second, Boethius boldy asserts that the ability to judge music is superior to the ability to craft and perform music. Within this model of music, the music theorist and literary critic are both superior to the musician and the poet. The ability to judge is always to be preferred over the ability to craft. In the long war between philosophy and poetry, philosophy always wins.

Whether or not poets like Dante would have agreed with Boethius that the practice of their art was inferior to those who judge art, especially since arts are, by definition, intended to be practiced, it is interesting to consider that medieval poets, as a kind of musician, may have conceived themselves to be craftsman that used the tools of grammar, logic, rhetoric, and music (or the entire quadrivium if one is Boethius or Dante!) to construct their art while looking up at the stars.

Lesley-Anne Dyer Williams

Public Humanities Postdoctoral Fellow

Medieval Institute

University of Notre Dame

Further Reading

Ancius Manlius Severinus Boethius. Fundamentals of Music. Edited by Claude V. Palisca. Translated by Calvin M. Bower. New Haven and London: Yale University Press, 1989.

Copeland, Rita, and Ineke Sluiter. Medieval Grammar and Rhetoric: Language Arts and Literary Theory, AD 300 -1475. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2009.

Dante Alighieri. Dante: Convivio. Translated by Andrew Frisardi. New edition. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2022.

Fournier, Michael. “Boethius and the Consolation of the Quadrivium.” Medievalia et Humanistica, no. 34 (2008): 1–21.

John of Salisbury. The Metalogicon. Translated by Daniel D McGarry. Berkeley: Calif. U.P., 1962.

Martianus Capella. Martianus Capella and the Seven Liberal Arts. Translated by William Harris Stahl, Richard Johnson, and E.L. Burge. Vol. II: The Marriage of Philology and Mercury. 2 vols. Records of Western Civilization 84. Columbia University Press, 1992.

Minnis, A. J., and A. B Scott, eds. “”Placing the Poetics: Herman the German; An Anonymous Question on the Nature of Poetry.” In Medieval Literary Theory and Criticism c.1100–1375: The Commentary Tradition, Revised. Oxford: OUP, 1991.

O’Daly, Gerard J. P. The Poetry of Boethius. Chapel Hill and London: The University of North Carolina Press, 1991.

Stahl, William Harris, Richard Johnson, and E.L. Burge. Martianus Capella and the Seven Liberal Arts. Vol. I: The Quadrivium of Martianus Capella. 2 vols. Records of Civilization, Sources and Studies 84. New York: Columbia University Press, 1971.

Woods, Marjorie Curry. Classroom Commentaries: Teaching the Poetria Nova across Medieval and Renaissance Europe. 1 edition. Text and Context. Ohio State University Press, 2017.

Woods, Marjorie Curry. Weeping for Dido: The Classics in the Medieval Classroom. 1st ed. Vol. 1. E. H. Gombrich Lecture Series. United States: Princeton University Press, 2019. https://doi.org/10.1515/9780691188744.

Lesley-Anne Dyer Williams is a Professor for Memoria College’s Masters of Arts in Great Books program and graduated with her doctorate from the University of Notre Dame’s Medieval Institute in 2012. She was also the founding director Liberal Arts Guild at LeTourneau University. Her research focuses upon twelfth-century Platonism and poetry, especially Thierry of Chartres and Bernard Silvestris.

[1] Distinctions made by Thierry in the Heptateuchon.

[2] Huglo, “The Study of Ancient Sources of Music Theory in the Medieval University.”