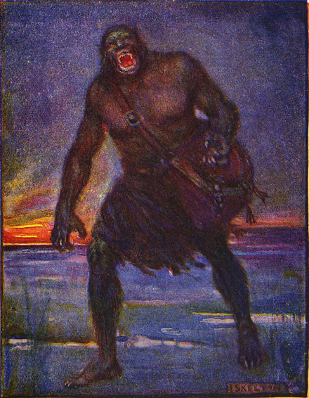

With the possible exception of certain stories about King Arthur, Beowulf is probably the best-known work of English medieval literature, and it is likely one of the oldest works as well predating early English Arthurian literature, such as Sir Gawain and the Green Knight by around six hundred years and Thomas Mallory’s Le Morte d’Arthur [The Death of Arthur] by around seven hundred years.

Beowulf has deep roots in popular culture as has long been taught in the English curriculum in the United Kingdom, the United States, Australia, New Zealand, and many of the former British colonies and current British Commonwealth. Beowulf has been remade into comics such as DC Comics’ Beowulf (1975), Gareth Hinds’ Beowulf: A Graphic Novel (2007), Stern’s Beowulf: The Graphic Novel (2007), and Santiago Garcia’s Beowulf (2016); novels such as John Gardner’s Grendel (1971), Michael Crichton’s Eaters of the Dead (1976), Susan Signe Morrison’s Grendel’s Mother: The Saga of the Wyrd-Wife (2015), and Maria Dahvana Headley’s The Mere Wife (2018); films such as Robert Zemeckis’ Beowulf (2007), Sturla Gunnarsson’s Beowulf & Grendel (2005), John McTiernan’s The 13th Warrior (1999), and television series such James Dormer’s Beowulf: Return to the Shieldlands (2016) to name just a few of the more recent and successful adaptations of this famous medieval poem.

Of course, medievalism is also popular in children’s literature and adult cartoons. Nevertheless, I will admit I was somewhat more surprised to notice the poem’s influence in children’s cartoons. My intersecting identities as a medievalist and a father invite me into the rich world of children’s literature, and as someone who enjoys a good story in any form, there are certain television shows that my daughter likes to watch that I too find entertaining. Little did I expect to encounter Beowulf and more specifically the character of Grendel in two children’s cartoons that mobilize and rework Beowulf into their narratives: Disney’s Amphibia (2019-2022) and Cartoon Network’s Adventure Time (2010-2018).

In Disney’s Amphibia one two-part episode which seems draw directly from Beowulf is season one’s episode fifteen, “A Night at the Inn; Wally and Anne.”

The first part of the episode, “The Night at the Inn” starts with a journey to a “creepy lagoon” right by a “scary forest” in a woodland horror setting—the mood is suspenseful and disconcerting—a dark and stormy night as they travel through lands filled with frightening creatures. Eventually they end up at a spooky yet cozy inn, a cottagey bed and breakfast run by a family of horned bullfrog people. After a haunting night, the story unfolds as an adaptation of the Grimm Brothers’ Hänsel und Gretel “Hansel and Gretel” with the bullfrog folk as the cannibal family. It is Polly, the tadpole, who ultimately thwarts their murderous plans and proves herself to her family.

Of course, cannibalism and monstrous families feature also in Beowulf, and the second half of the episode “Wally and Anne” mobilizes the characterization of Grendel in the representation of the enigmatic Moss Man.

The second part of the episode “Wally and Anne” also borrows from Sasquatch lore, conflating Bigfoot and Grendel into the mysterious Moss Man. As the show progresses, the Moss Man shifts from being regarded as a cryptid monster to a beautiful and misunderstood creature, in a reparative move in line with other modern adaptations that present sympathetic portraits of the monster.

“Wally and Anne” starts with Anne seeing the shadow of a creature, much like Grendel the sceaugenga “shadow walker” (703) and she follows it into the monster’s murky domain. She then catches a glimpse of the majestic creature, but it hears her and takes off into the woods. Other characters believe the Moss Man is a myth, which frames the remainder of the episode, with the exception of “the town weirdo” Wally, who swears to have also seen this creature “deep in the moors, where it makes its home and feeds on mist.” Wally further describes the monster to Anne, saying “Skin of moss it had. Took my hand clean off it did,” (as happens to Grendel in Beowulf), but as Anne is quick to point out, Wally has both his hands in tact, signaling his role as an unreliable witness and narrator.

The Moss Man, like Grendel, lurks in the mistige moras “misty moors” (162), and this place name is used to describe both the realms of Grendel and the Moss Man. The eerie swamp resembles the monster mere and marshy haunts of the Grendelkin. As Anne and Wally search for the Moss Man together, Wally warns the “journey will be fraught with peril” and sings a song to his accordion playing with the lyrics, “the Misty Moors are dark and grey” an allusion to the Grendel’s haunted fens. The place name “Misty Moors” is repeated throughout the episode to characterize the eerie swamplands where the Moss Man roams.

However, the behavior of the Moss Man tracks closer to Sasquatch, huge and terrifying, but more elusive and mysterious than dangerous, though of course Grendel and his kin are also described as mysterious in the compound helrune (163). In “Wally and Anne” the plot hinges on the misfit team who become unlikely friends in their failed attempt to take a picture of the creature once they find it at last. Although Wally first describes the Moss Man as Grendelish, by the end we learn that the creature is no threat to the local community.

The tenth and final season of Adventure Time kicks off with and episode called “The Wild Hunt” which includes a medieval-inspired, Bayeux Tapestry-inspired, image of the protagonists Finn and Huntress Wizard in the center with a monstrous hand on the right and fleeing banana guards on the left. In addition to foreshadowing the plot, this signals the heavy influence of medieval literature that features in the forthcoming episode.

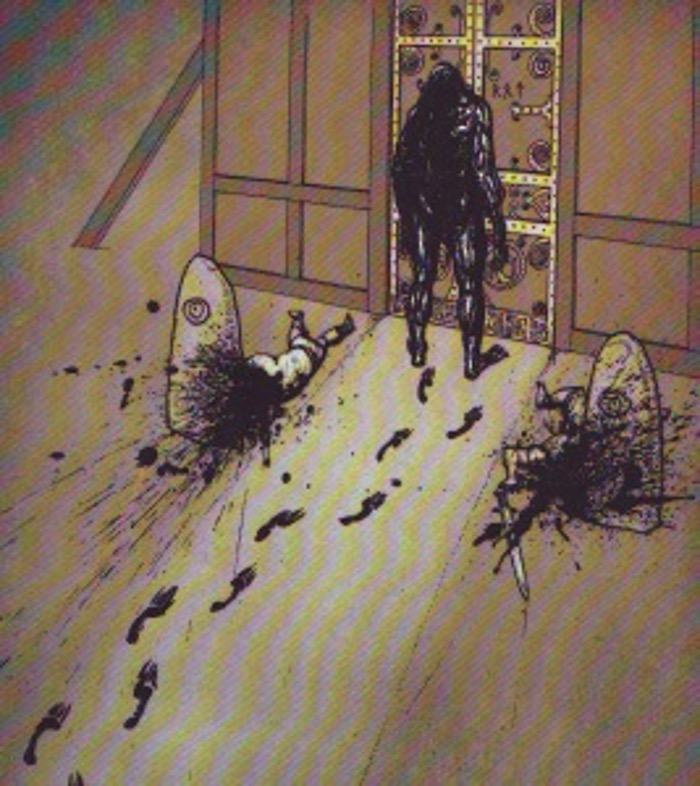

The episode begins in a dark hall with two banana guards, members of Princess Bubblegum’s royal army, just outside their Gryffindor-like “dormitory” where the soldiers agree that they are afraid. This in media res intro creates suspense from the very start of the episode, and the audience’s epistemic limitations invites fears of the unknown thereby mobilizing the psychology of terror. After some debate on how this should be accomplished while also holding their spears, the banana guards decide to hold hands. Just then, a huge, monstrous hand reaches from offscreen and grabs them both.

After dispatching the guards, the gigantic and vicious monster then enters the dormitory and attacks the soldiers at night, slaughtering its victims. This scene from “The Wild Hunt” is one of terrifying carnage and comes straight out of Beowulf. The Adventure Time heroes (Finn the human and Jake the magic dog), who have been recruited to slay the banana fudge monster, are there hiding, yet they do not stop the monster from grabbing a sleeping guard just like in Beowulf, when Grendel grabs and devours Hondscio before Beowulf makes any counter move (739-745). In fact, in both Beowulf and Adventure Time, it is not until the monster reaches out to grab the incognito hero (Beowulf and Jake respectively) that an epic battle ensues. Moreover, just as Beowulf famously refuses to use blades against Grendel (426-41), and allows his enemy to escape back to the monster-mere of the Grendelkin, Finn likewise is repeatedly unable to use his sword against the banana fudge monster and therefore it escapes into the wilderness seeking its home. These narratological parallels pay homage to the medieval poem and demonstrate how medievalism is alive and well in popular culture including children’s cartoons.

After the opening scene, there is a flash back to earlier that morning when Finn and Princess Bubblegum prepare for a baseball game and stumble upon what Bubblegum calls “a banana fudge massacre.” The surviving banana guards report to their princess and describe the monster’s initial midnight assault on the Candy Kingdom, and they characterize the murders as cannibalism stating “a terrible monster kidnapped squadron 5. It looked like a banana, but it peeled other bananas.”

Like Grendel is described as mara þonne ænig man oðer “greater than any other man” (1353), the banana fudge monster has what Jake calls “crazy devil strength” and carries the corpses away to his home, stealing warriors like plunder. Since Finn is unable to kill the monster, he is forced to hunt down the monster in its lair, like Beowulf does with Grendel. The remainder of the episode involves an epic hunt with Finn’s friend, Huntress Wizard, who calls the monster “an invasive species that’s destroying the local ecosystem with its nasty hot fudge” and names it “The Grumbo.”

Indeed, “The Wild Hunt” even explores some of the essential questions and core tensions posed in Beowulf. The psychological drama that preoccupies the rest of the narrative focuses on Finn’s internal struggle as he tries to overcome guilt for killing his monstrous, plant-like doppelganger, Fern. Fern’s untimely death at Finn’s hands forces the hero to reflect on his previous use of excessive violence and to question his retaliatory actions, blurring the distinction between heroism and monstrosity and destabilizing both concepts. As in Beowulf, heroes and monsters are juxtaposed and paralleled in the episode of Adventure Time, highlighting how these categorizations are often a matter of perspective and how heroic deeds and monstrous actions are virtually identical in substance. In attempting to talk himself into attacking the Grumbo, Finn tries to tell himself “I don’t care why you’re doing this or if you’ve had a tragic past. I’m hard like that,” but his tone betrays his hesitation as he sympathizes with the monster.

Nevertheless, with the support of Huntress Wizard, Finn is ultimately able to slay the Grumbo, but like in Beowulf (1605-1611), the sword used to stab the monster melts down to the hilt as a result of the creature’s toxic blood (which in the show is a form of hot fudge).

Adventure Time makes their medievalism perhaps even more explicit later in the fifth episode of final season titled “Seventeen” in which a previous character thought to be dead, Fern, returns and surprises Finn on his 17th birthday as the Green Knight. The mysterious Green Knight rides upon a shimmering green horse and offers Finn a green battle axe as a present before challenging him to a beheading game. As “The Wild Hunt” reworks and refashions the plot of Beowulf, “Seventeen” similarly draws directly from the 14th century Middle English alliterative poem, Gawain and the Green Knight. But that’s a discussion for a future post.

Richard Fahey, Ph.D

University of Notre Dame

Medieval Institute