Through my dissertation research on the middle Byzantine Maeander Valley in Western Asia Minor (modern Türkiye), I had become fascinated by an eleventh-century estate ledger, known as the Praktikon of Adam, and how Byzantine surveyors described landscapes in technical language.[1] The boundary description or periorismos was composed of formulaic phrases describing the route taken needed for a surveyor to encircle a property. Sometimes, but not always, these descriptions are accompanied by measurements, which can be rationalized from the Byzantine units into meters. I am interested in mapping these boundary descriptions to compare them with the results of archaeological field surveys.

This blog entry will be a short musing upon the shifting role of precision in the tradition of Byzantine land survey. In our modern world, cartographic precision has become an unquestioned backdrop to how we view landscapes. We rarely feel the need to justify spatial precision when representing a landscape on a map (i.e., Fig. 1). Such a casual aesthetic commitment to cartographic precision has no counterpart among ancient and medieval representations of landscapes. Therefore, any study of boundary descriptions must rest upon why such precision was necessary. The presence (and absence) of that precision reveals the underlying motivations of the surveyors. Such motivations must be considered when using these documents to understand Byzantine landscapes.

Surveying for Taxation

The original goal of Byzantine land survey was calculating the tax burden of a property. Twelve Byzantine survey manuals survive, which were written to instruct new bureaucrats on how to survey the land and then use those measurements to calculate area. The study of these textbooks provides a starting point for understanding how and why Byzantine surveyed the land.[2] Surviving documents found in Byzantine archives, such as the Praktikon of Adam, show how the recommendations of these textbooks were or were not enacted.

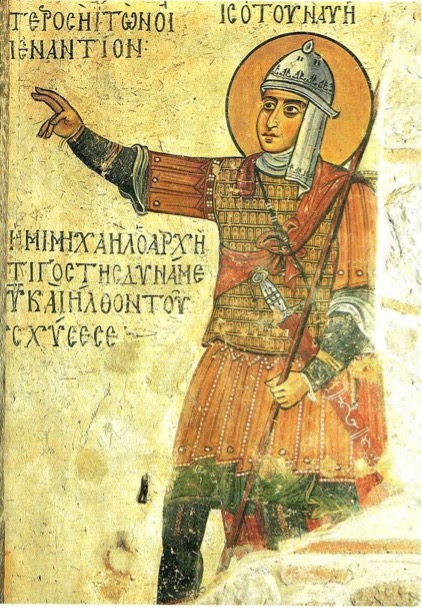

The purpose of taxation prioritized the taking of measurements. Land is measured with ropes (schoinioi or sokaria). An illustration from a Byzantine Octateuch (Fig. 2) shows the survey of land in action. I took the title of the blog entry from the Byzantine Greek written on this image: “A cord laid tight loosens discord” – akin to the English proverb “Good fences make good neighbors.” The whole set of illustrations show a Byzantine twist on the delineation of land in the last ten chapters of the Book of Josuah in the Old Testament. These ropes were not just a tool but also the most important unit of measurement. Ropes are divided into fathoms (orgyia), based on two different criteria: the quality of the soil or the region of the empire. The 10-fathom rope was the standard for high quality soils, while lesser soils were measured with a 12-fathom rope. In Thrakesion (western Asia Minor), the 10-fathom rope was the standard for all soils.

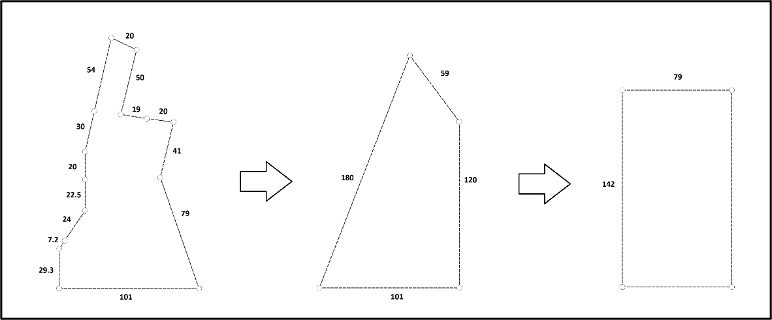

The desired product of the fiscal survey was calculating the area of many properties efficiently. Therefore, the methods were less than geometrically sound. Or as Jacques Lefort and his team wrote: “The geometric technique of the tax office is nevertheless very simple, since it consists, in a world implicitly conceived as almost everywhere orthogonal, in multiplying the length by the width. It therefore owes nothing to geometric science and is in fact resolved by arithmetic, and even then, only by the art of multiplying well.”[3] In other words, no field cannot be reduced to a rectangle (Fig. 3). While scholars in the past attributed these imprecise methods to the decline of geometry in the Middle Ages, the Byzantines were capable of complicated geometry when it suited the task at hand. Precision in individual measurements was not important for the tax office.

Finally, the tax surveyors were interested in a space, but not in a place. The taxation surveys of fields are often unmoored from their landscapes. The precise location of the field made little difference when calculating the tax burden. Therefore, without other correlating data, the precision of the tax survey, while useful for maintaining an empire, provides little help to the archaeologist.

The Motivation of the Boundary Description

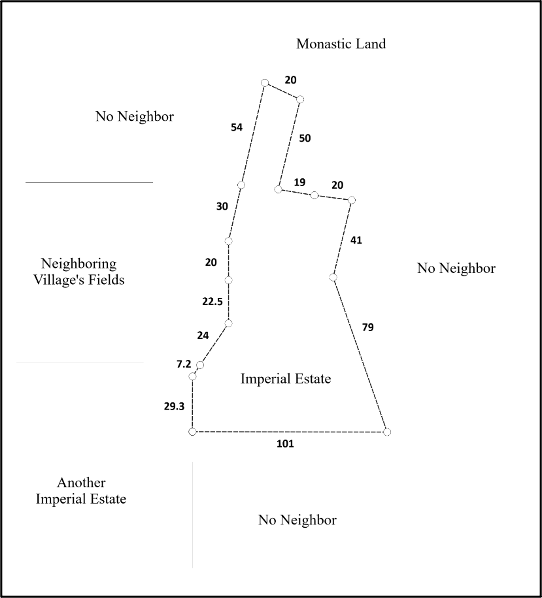

On the other hand, a boundary description represents a diverging motivation for land survey within the same tradition. Not all have measurements, but when they did, the individual measurements appear to be more important than the whole. The description is grounded in the specifics of the landscape. The precision of individual measurements included often outstrips the needs of calculating area (Fig. 3). Instead, precision correlates with the presence of properties owned by neighbors of the estate (Fig. 4). Instead of taxation, the purpose of the precision of the boundary description appears to be related to the control of land. Theft of land by unscrumptious neighbors was a growing problem from the late eleventh century through to the end of Byzantium. The Praktikon of Adam reveals two such cases where theft was discovered. Still, the former was recorded in a boundary description, while the latter still relied upon the taxation-based survey technique, which shows that both techniques could theoretically reveal theft even if the boundary description appears better equipped.

While there is more research to be done, I am still convinced that the embeddedness of the boundary description within their respective settings and the incorporation of measurements into the descriptions can make these technical descriptions valuable comparanda to archaeological survey data in reconstructing the landscapes of the Byzantine world.

Tyler Wolford, PhD

Byzantine Studies Postdoctoral Fellowship

Medieval Institute

University of Notre Dame

[1] M. Nystazopoulou-Pelekidou, ed., Βυζαντινὰ ἔγγραφα τῆς Μονῆς Πάτμου. Volume 2. Δημοσίων λειτουργῶν. Athens: National Institute of Research, 1980, Document 50.

[2] J. Lefort, B. Bondoux, J.-Cl. Cheynet, J.-P. Grélois, V. Kravari. Géométries du fisc byzantin. Réalités Byzantines 4. Paris: Éditions P. Lethielleux, 1991.

[3] Lefort et al., Géométries du fisc byzantine, 244.