“Their king [the kings of Daqin] is not a permanent one, but they want to be led by a man of merit. Whenever an extraordinary calamity or an untimely storm and rain occurs, the king is deposed and a new one elected, the deposed king resigning cheerfully. The inhabitants are tall, and upright in their dealings, like the Han [Chinese], whence they are called Da-Qin, or Han [1].”

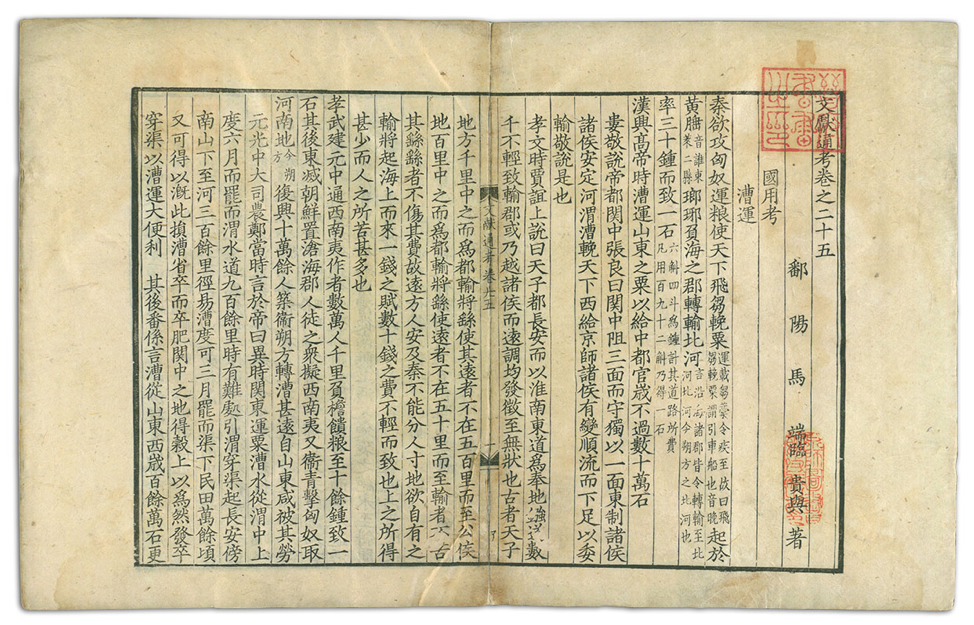

Ma Duanlin

This description of the Byzantine Empire by the 13th-century Chinese historian Ma-Duanlin would startle his Byzantine contemporaries used to palace intrigues worthy of the finest episodes of a popular tv show.

Chinese literati and intellectuals identified the ancient Roman Empire as Da Qin 大秦 or Great Qin. The term which emerged during the Han Dynasty (202 BC – 220 AD) is evocative of China’s perception of their western counterparts whom they regarded as equal to themselves. Whereas China ruled over the eastern parts of the world, somewhere far in the west, a counter China held the balance of the world. Under the Tang, another, more phonetically accurate term, Fu Lin 拂菻, emerged to describe Byzantium, the medieval iteration of the Roman Empire. Chinese historians probably adopted the more accurate Fu Lin from their Eastern Iranian and Turkic neighbors (Middle Persian: Hrum; Bactrian: φρομο), who were used to trading with the Byzantine Empire in the 6th and 7th centuries.

Even though Chinese historians knew that Da Qin and Fu Lin were the same entity, knowledge of a powerful empire far in the west did not prevent them from intermixing facts and fictions. According to an eleventh-century account, the mighty Fu Lin could field a large army of a million men. At the head of such an immense army, the kings of the Romans ruled supreme. Fu Lin enjoyed the rule not only of astute military kings, but also of the wisest men in Western Eurasia. Unlike the hereditary Chinese monarchies, Chinese historians claim that the Romans elected their kings from among the wisest and most meritorious. Deposed kings did not oppose their fate, but resigned quietly. Rather than causing considerable troubles and protesting, they stepped down and cheered for their successor, a testimony of their great wisdom.

Ma Duanlin presents Da-Qin/Fu-Lin as a utopia ruled by competent, quasi-philosopher kings. Ironically, the Chinese historian who died in 1322, was a (very distant) contemporary of some of the most gruesome depositions to take place in Byzantium. Among the many examples, and a list far too long for a blog post, stands the infamous Michael VIII Palaiologos (r. 1261-1282). Michael emerged as the sole emperor of Byzantium after brutally blinding his rival, the very popular John IV Laskaris, an eleven-year-old child. Michael’s contemporaries vilified the emperor for his wretched behavior. Arsenios Autoreianos, the patriarch of Constantinople, excommunicated Michael as a response to the blinding of Laskaris. One may also be tempted to summon the case of John Kantakouzenos who ruled between 1347 and 1354. Kantakouzenos, who became emperor after six years of civil war, triumphed over his rivals thanks to the help of the Turks of Orhan Ibn Osman, the son of the founder of the Ottoman Beylik. The early Ottomans benefited from the Byzantine civil war and gained a European fortress for the first time. Could Ma Duanlin, who relied on sources tracing back to the Han Empire, have seen Roman institutions as immutable and expected the emperors of the 13th century to be elected in like fashion to the consuls of the Roman Republic? Nevertheless, the cold reality of palace coups in 13th-century Byzantium was a far cry from the elective utopia described by the Chinese historian.

Perhaps more tantalizing are the many fantastic elements found in Chinese descriptions of the Roman Empire and Western Eurasia. The same Ma Duanlin claims that the Romans were fond of a highly peculiar type of pearl. The Romans collected these pearls of jade, not from mollusks, but from the saliva of a curious species of bird. Likewise, according to Chinese historians, the Romans lived near a mysterious group of dwarves. These dwarves, a far cry from Tolkien’s rugged miners, were allegedly so small that they constantly looked towards the skies, fearing cranes who dined on their kin. The dwarves relied upon the Roman armies to fend off the cranes. As a compensation for their help, it is said that they paid their Byzantine benefactors with many precious jewels and gems.

Although we may never find out where Chinese historians got some of this information, the far west of Eurasia fascinated the imagination of generations of Chinese literati who saw it as a land of myths and legends where wise kings cohabitated with fantastic birds and mysterious dwarves.

R.T., PhD Candidate

University of Notre Dame

Read more:

In English: Friedrich Hirth, China and the Roman Orient Researches into their Ancient and Mediaeval Relations as Represented in Old Chinese Records, (Leipsic and Munich, 1885).

In Turkish: Bahaeddin Ögel, “Göktürk yazıtlarının Apurimları ve Fu-Lin Problemi,” Türk Tarih Kurumu Belleten 9 (1945): 63–89.

In Chinese: Jianling Xu, “Bàizhàntíng Háishì Sài Ěr Zhù Rén Guójiā? Xī ‘Sòng Shǐ·fú Lǐn Guó Chuán’ de Yīduàn Jìzǎi,” The Journal of Ancient Civilizations 3/4 (2009): 63–67.

[1] Original text and translations in Friedrich Hirth, China and the Roman Orient Researches into their Ancient and Mediaeval Relations as Represented in Old Chinese Records, (Leipsic and Munich, 1885). Translations are from Hirth.