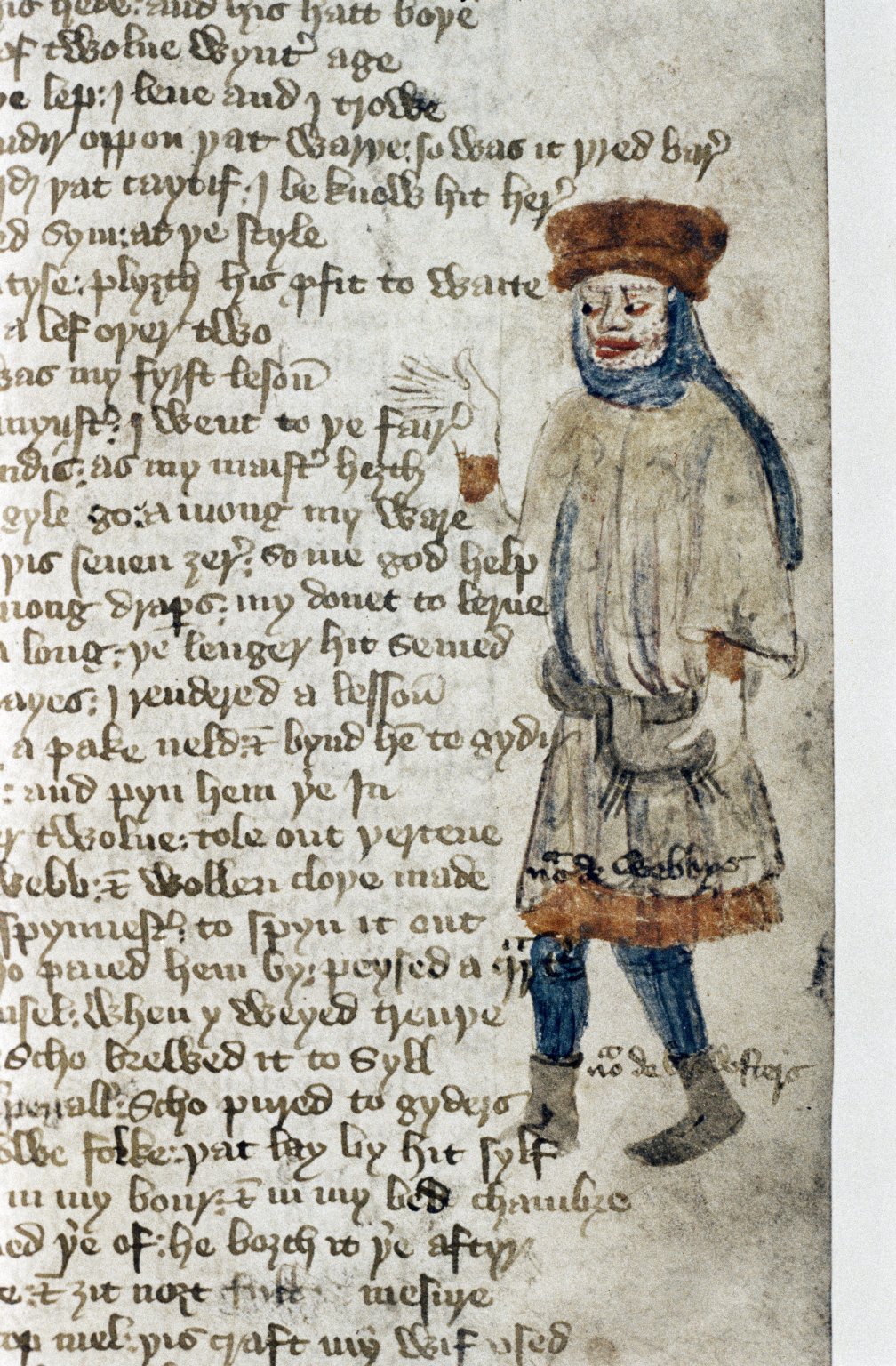

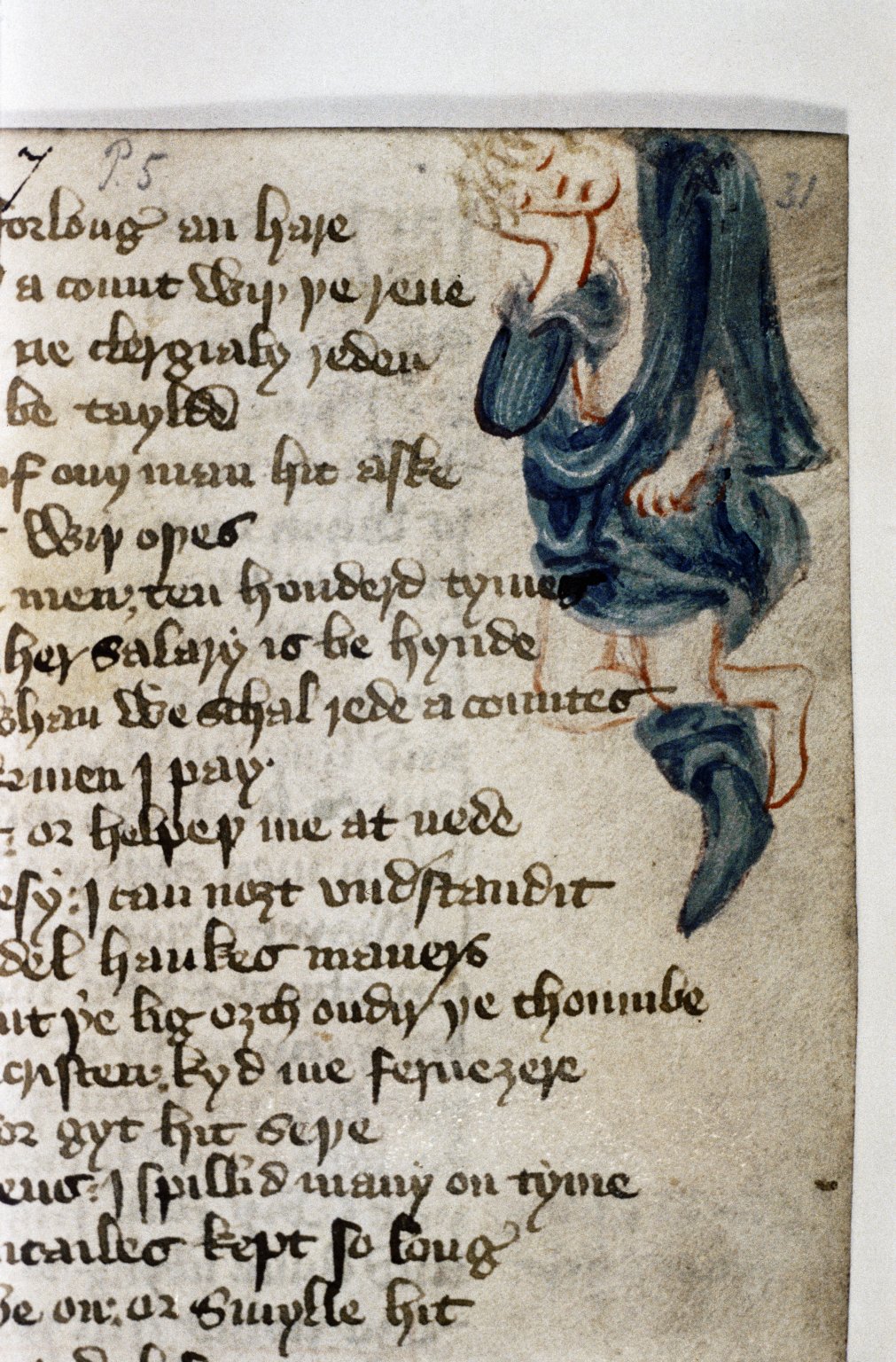

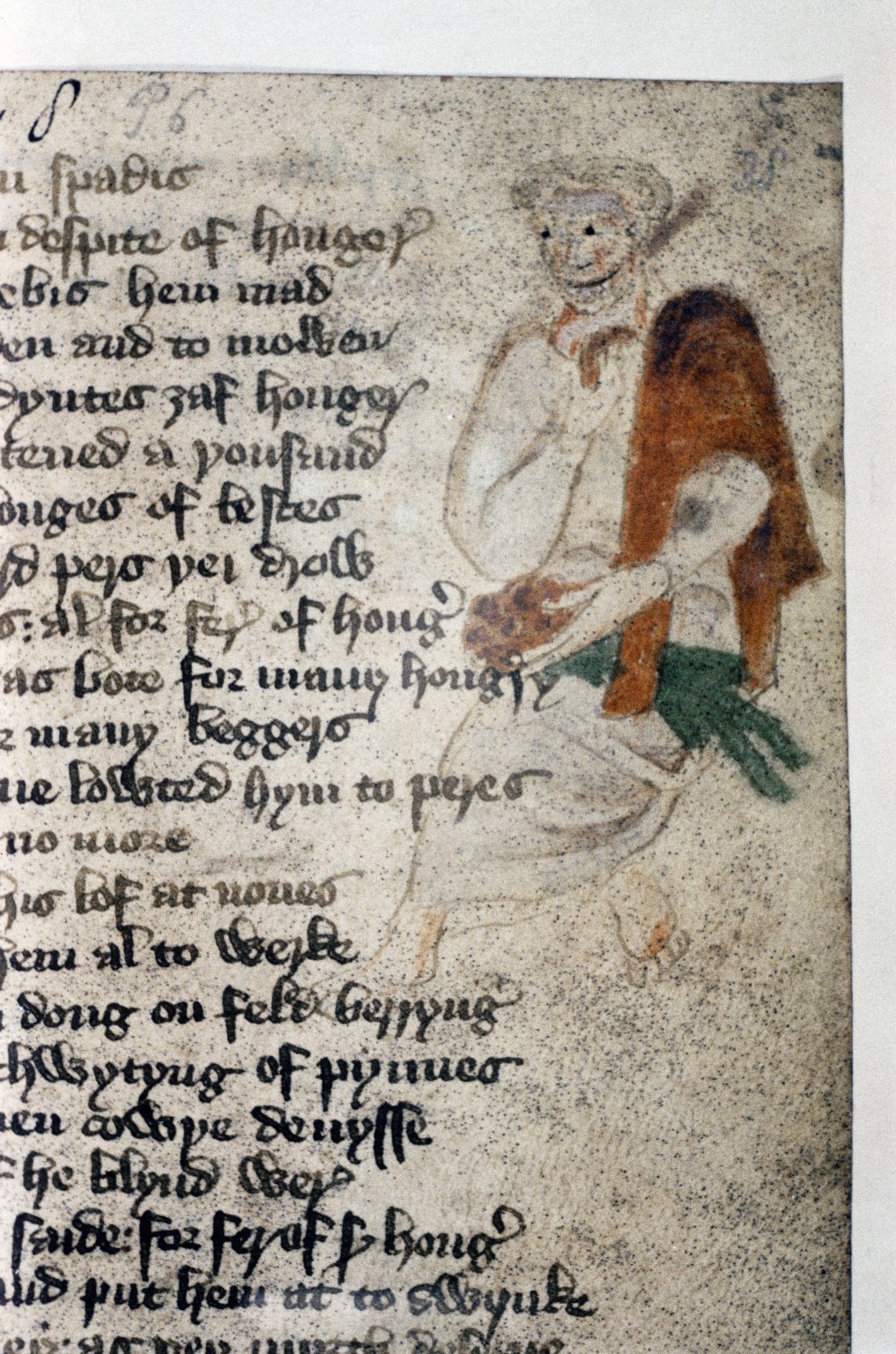

Sir Gawain and the Green Knight, the Middle English alliterative Arthurian poem, has long captured the imagination of audiences, medieval and modern. Recently, Valiant Comics has adapted the Sir Gawain and the Green Knight into a comic titled “Immortal Brothers: The Tale of the Green Knight” and brought the poem to modern audiences (2017). The same year, Emily Cheeseman adapted Sir Gawain and the Green Knight into a graphic novel (2017), which was funded by Kickstarter and which is now publicly available online.

Film adaptions of Sir Gawain and the Green Knight have also emerged in modern times, including Steven Weeks’ two movies based on the medieval story: Gawain and the Green Knight (1973), and then about a decade later, The Sword of the Valiant: The Legend of Sir Gawain and the Green Knight (1984), which famously features Sir Sean Connery as the Green Knight. While Weeks draws primarily from Sir Gawain and the Green Knight in his film adaptations of the medieval poem, he also borrows from other Arthurian legends, such as the tale of Sir Gareth in Thomas Malory’s Le Morte d’Arthur and Yvain, the Knight of the Lion by Chrétien de Troyes.

Moreover, last year a new film adaption of the poem, titled The Green Knight (2021), directed, written, edited, and produced by David Lowery, was released in theaters. This recent movie adaption of Sir Gawain and the Green Knight drew both praise and opprobrium from critics, prompting me to view and write my own review of the film. The Green Knight stars Dev Patel as Gawain, a nephew of King Arthur in this adaptation, who embarks on an epic quest to test his chivalry and confront the Green Knight.

But today, as I previewed in my previous post on adaptations of Beowulf in modern cartoons, I want to discuss the introduction of a character adaptation of the Green Knight in the final season of Cartoon Network’s Adventure Time. The episode that features and centers the Green Knight is called “Seventeen” (Season 10 Episode 5), in which the plot borrows substantially from the medieval alliterative poem, despite significant redactions and reworking on certain characters and themes from the source text.

As in the Middle English romance, the episode begins with feasting and a celebration. In Sir Gawain and the Green Knight, King Arthur and his court at Camelot are celebrating Christmas and Yuletide. In Adventure Time, the celebration centered on the 17th birthday of Finn the Human, who is also the main hero and one of the primary protagonists of the show, at Princess Bubblegum’s court in the Candy Kingdom. In both the medieval poem and modern cartoon series, the Green Knight rudely barges into court, unannounced, uninvited and riding on his green horse, before offering a green battle axe and proposing a dangerous challenge.

In “Seventeen” when the stranger enters, Finn exclaims “you’re green,” to which the guest responds “I’m the Green Knight.” Like in the medieval poem, Adventure Time‘s Green Knight is exceedingly green, from his armor and clothes, to his hands and face, and even his mount and weapon are all shades of green. The special attention the cartoon gives the green axe and green horse pays homage to the Middle English romance, which contains detailed descriptions of the green man, his green axe and his green steed.

In both the television series and Middle English poem, the Green Knight’s arrival is shrouded in anticipation and ladened with suspense. Just as in the original poem, the Green Knight in Adventure Time is a mystery knight, come to challenge the champion and test his opponent’s heroism and mettle. In keeping with its source, Adventure Time makes games central to the episode, beginning with the very game featured in the original poem.

In Adventure Time, since it is Finn the human’s 17th birthday party, when the Green Knight arrives at the court of Princess Bubblegum, he gifts his green axe to Finn for the occasion. The Green Knight greets Finn by saying: “And before you ask, of course I brought you a birthday present. It’s a battle axe.” The Green Knight follows up with a cryptic caveat “But only if you play me a game for it.” As Gawain does in the Middle English romance, Finn accepts the battle axe and the Green Knight’s challenge, deciding to game with the mysterious guest.

As in Sir Gawain and the Green Night, the first birthday contest in “Seventeen” is a weird beheading game. When Finn asks which game they will play, the Green Knight describes the game: “Oh this game is called all you have to do is strike me with it and it is yours.” Finn struggles with the idea of “axing a stranger” but soon has a revelation. Noting the absence of his partner, Finn assumes that the mysterious Green Knight is nothing more than a birthday prank orchestrated by his best friend Jake, so the hero plays along and is unfazed by the uncanny strangeness of the proposed game. Finn deals what appears to be a death-dealing blow to the neck, decapitating the Green Knight, much like Gawain does in the original poem.

Again, as in its source, the Green Knight in “Seventeen” proves to be some sort of undead being, able to simply pick up and replace his head after his beheading. It is at this point that Jake arrives, signaling that the Green Knight is not an elaborate birthday hoax by Jake, and what was planned as a fun birthday turns into a fight for his life. Citing fairness, the Green Knight isolates Finn from the rest of his friends so that they cannot aid him, or warn him of any foul play on the part of the Green Knight.

Unlike in the Middle English romance, in “Seventeen” Finn asks for alternative games rather than allowing the Green Knight to return an axe stroke to his neck. This marks the major point of divergence in what follows as a loose adaptation. The stakes are set: if Finn wins, the Green Knight will reveal the mystery of his identity and the Green Knight makes plain his reward, stating, “if I win, chop, chop.”

The Green Knight is able to win the first contest through deception and subterfuge, ideas central to the source text as well, and then the Green Knight allows Finn to win the second contest without competing at all, undercutting his heroism. This ultimately proves the only game in which Finn defeats his opponent. Again, the Green Knight has a trick up his sleeve, this time the plan is to allow Finn to expend his energy and strength, giving the Green Knight the upper hand in the decisive game between Bubblegum’s champion and the mysterious guest.

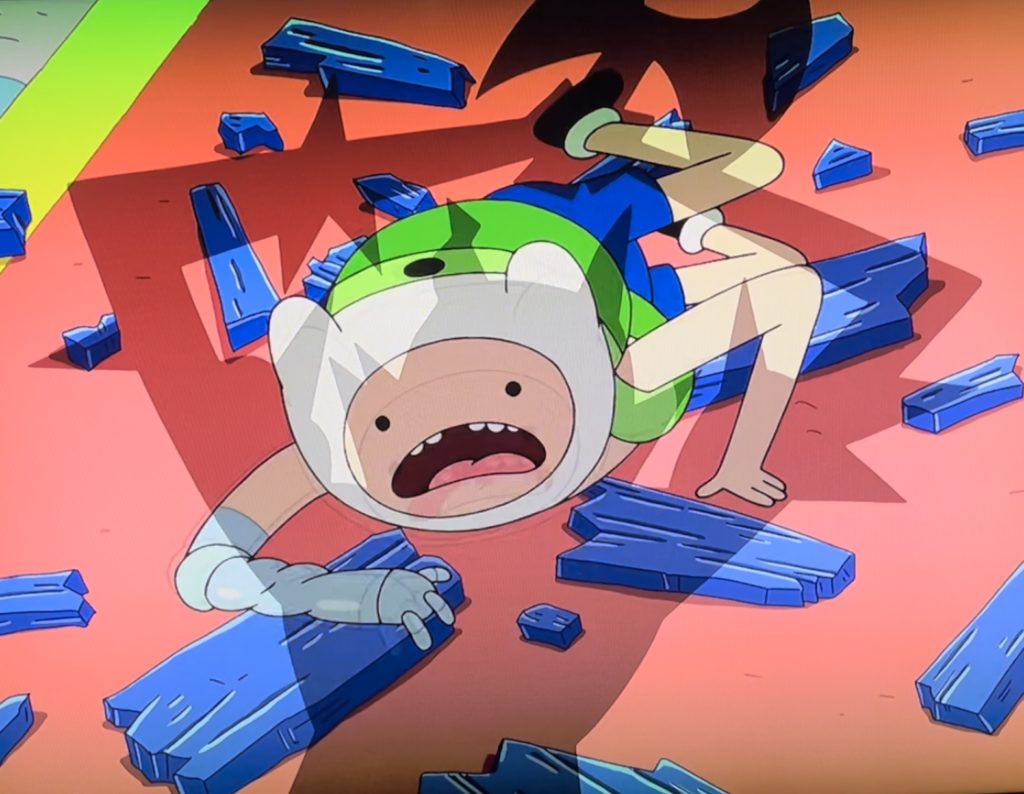

Finn recognizes the trick immediately, but Finn believes his “robot arm” will continue to provide him with an advantage in the final contest of strength: an arm wrestling match. While Finn is able to compete with the Green Knight until the first mystery is revealed, once the hero learns that the Green Knight is none other than Fern, his formerly deceased, plant-form doppelgänger, he becomes overwhelmed causing him to lose their last game. The surprise of the Green Knight’s identity disarms the hero and allows Fern to easily defeat Finn. Fern, in Green Knight form, smashes his enemy upon the table, breaking it, and leaving Finn on the floor, vulnerable and in shock, as the Green Knight approaches, axe raised and ready to deliver a fatal blow.

These additional games replace the hunting and bedroom games featured in the Middle English romance, but the narrative of “Seventeen” nevertheless realigns with the original plot as the hero ultimately fails and appears as if he is about to be beheaded by his opponent. In the medieval poem, the Green Knight is revealed to be Bertilak, the lord who houses Gawain and whose wife seduces him. But the double reveal includes the revelation the it was Morgana Le Fay (2446), a witch and King Arthur’s half sister, who sent the Green Knight to Camelot to test the Knights of the Round Table and frighten Queen Guenevere.

Similarly, in Adventure Time, the Green Knight is a servant of disgruntled, royal relatives. In “Seventeen,” the Green Knight is called off by his own steed, which is shown to be a mechanical horse in which three treacherous relations of Princess Bubblegum are hidden: Uncle Gumbald, Aunt Lolly and Cousin Chicle. The double mystery aspect of the cartoon mirrors the medieval poem’s dual reveal at the end of narrative, in both cases returning focus to intrafamily power struggles over the throne while simultaneously demonstrating the limitations of chivalry and the dangers of hubris. By the end, in both Sir Gawain and the Green Knight and “Seventeen” the royal champions are bested by the Green Knight, although in Adventure Time, the Vampire Queen Marceline is there to step in and scare off the intruders, causing the Green Knight to retreat into the night.

The way in which Adventure Time creatively adapts and reinvents Sir Gawain and the Green Knight for a broad modern audience carries forward the medievalism from “The Wild Hunt” (Season 10 Episode 1). Although at times the episode deviates dramatically from its source, Adventure Time makes the complex (at times enigmatic) medieval story both accessible and comedic, while retaining some of the key aspects including the fraught presentation of chivalry and heroism, thereby helping to set the stage for future generations of medievalists.