The Crusades reveal that medieval attitudes towards sexuality were not always rigid and repressed. In fact, medieval societies expressed varying levels of tolerance and fluidity depending on circumstances and necessity. Unlike what a simple understanding of the Crusades would imply, Christians and Muslims did not occupy such disparate spheres that sexual relations between them—even those as legitimate as matrimony—were inconceivable. At times, miscegenation was tolerated. Moreover, while attitudes towards sexual relations with the religious ‘other’ remained largely (though not always) negative, the factors that governed these attitudes varied.

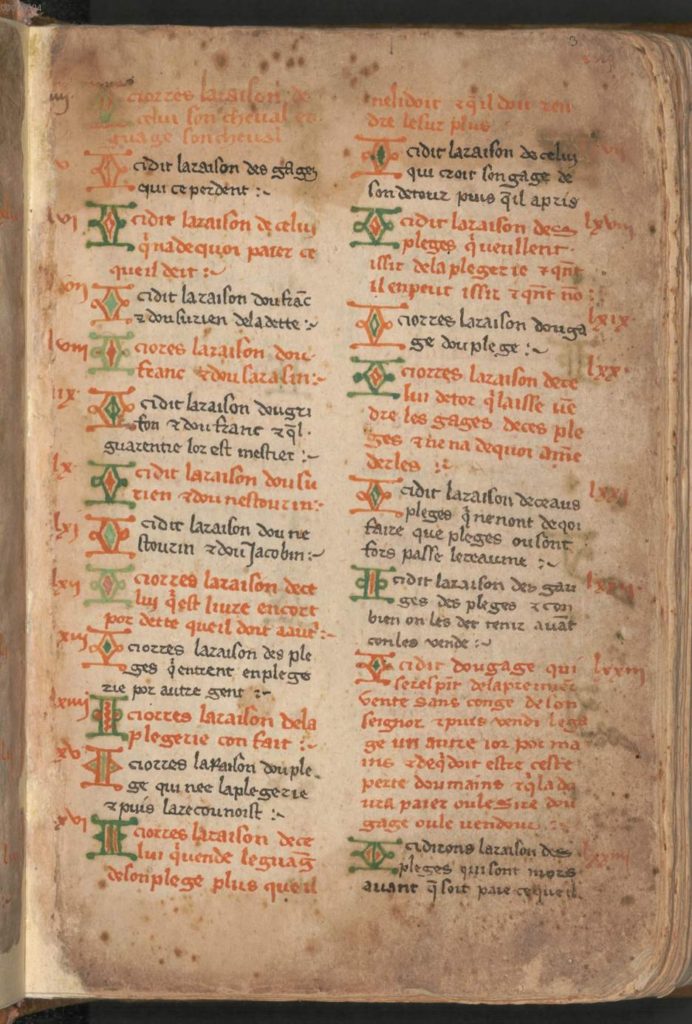

Literary sources and medieval chronicles reveal a complexity of attitudes and concerns. Lynn Ramey, in her 2001 work Christian, Saracen and Genre in Medieval French Literature, has explored medieval attitudes towards miscegenation as expressed in Frankish literature.[i] A genre of romance literature, called Chansons de Geste, that became popular in the Frankish world between 1150 and 1250, reveal anxieties over interfaith marriage in Western Christendom. This genre of literature reveals racial biases against Muslims, but at the same time, present models of marriage between Muslims and Christians that accommodate these biases. A recurring component in these poems is the scene of baptism: a symbolic enactment of washing away the spiritual dirtiness of the previous faith to embrace the purity of Christianity. But the dirtiness is more than spiritual. These texts reveal the concern over biological inheritance from the Muslim spouse in interfaith marriages. In her article, “Medieval Miscegenation: Hybridity and the Anxiety of Inheritance,”Lynn Ramey explores reproductive anxieties that texts such as King of Tars reveal, and argues that there was serious apprehension over whether the offspring of an interfaith marriages would be healthy. She traces these fears to Aristotelean, Galenic, and Hippocratic models of reproduction that Christendom had inherited. Ramey suggests that religious traits were perceived as biological and inheritable, and most importantly, undesirable. In the King of Tars, for instance, a marriage alliance between a “Saracen” king and a Christian princess leads to the birth of a defective offspring. However, the conversion of the Muslim king to Christianity corrects the offspring’s birth defects. Christian features, therefore, were desirable while Muslim ones were not. Thus, religion determined biology. King of Tars, she argues, offers conversion as a suitable means of eliminating undesirable traits. Thus, the “dark” Saracen king turns “white” upon conversion and the “blob” of an offspring becomes a beautiful boy following his baptism.[ii]

In the poem, King of Tars, the desired inheritable physical traits are achieved upon conversion. However, in other poems, there is less certainty over the mutability of physical traits. In these poems, assimilation is permissible only when the Muslim fulfils two major criteria: he or she fits the Christian standard of beauty and he or she willingly converts to Christianity. The Capture of Orange, composed around 1150, for instance, narrates the tale of a Crusader knight, William of Toulouse who falls in love with the beautiful and noble-hearted, yet, religiously “misled” Saracen queen, Orable of Orange. In the poem, the Crusaders describe the physical beauty and sexual appeal of the ‘Saracen’ queen in the following terms:

King Teebo’s wife, so fair of hair and head:

You’ll never find her peer for loveliness

In Christendom or any Pagan realm!

Such tenderness! Such slender hips and legs,

And falcon’s eyes, so bright and so intense!

Alas for youth and beauty so misled

In ignorance of God and His largesse!

How fine a place she’d make a Christian bed

For somebody who’d save her soul from hell![iii]

Orable, therefore, fulfils the Christian beauty standard by being ‘fair of hair and head’, and following the capture of Orange and the defeat of King Teebo, she converts willingly to Christianity in order to marry William. Similar to The Capture of Orange wherein the Muslim woman weds a Christian Knight, the Aye of Avignon, composed around 1190, features a noble-hearted Muslim King who is willing to leave his faith and his land behind in order to wed a Christian woman. Again, in this poem the Muslim man is honorable but, most importantly, handsome:

KING GANOR WAS as gracious and kind as he was bold.

In one hand he was holding a pilgrim-staff of oak,

But took off from the other a glove with stitches sewn.

The graceful hand beneath it was long, and pale as snow,

And, on its little finger, displayed a ring of gold.[iv]

Ramey points out that medieval romances read like legal treatises on marriage, recommending assimilation of those parts of Muslim culture that were perceived as non-threatening in Western Christendom and “othering” those aspects that were. The dark skin, for example, was alleged to be a physical sign of barbarism. However, the internal virtues of patience, tolerance and courage in a “Saracen were grudgingly admired.”[v]

These poems, thus, seek to balance the Christian penetration of Muslim culture by absorbing valuable traits of the latter while at the same time emphasizing the ultimate victory of the former. For instance, in King Ganor’s case, he is not required to change his name; while in the case of the queen in Capture of Orange, she is baptized as ‘Guibourc.’ The latter expresses the symbolic victory of Christianity over Islam through the male penetration of the female: the Christian knight acquires a Muslim wife by baptizing her. Moreover, since inheritance of name, title, and the honors associated thereof was paternal in Western Christendom, changing the woman’s name presented no problem. Further, there is little unease when a woman sheds her name upon marriage. On the other hand, all the desirable achievements associated with King Ganor’s name could not be inherited by his sons had his name changed. This would likely create cause for concern in the medieval imagination. Moreover, a man shedding his name stirs unease not quite on the same level as but somewhat similar to castration. The idea is that a man is cuckolded or less manly when he changes too much for his wife. So, the change has to be just enough to establish the superiority of Christianity, but not so much that it establishes the dominance of the woman over the man. Consequently, King Ganor’s name stays the same despite his baptism. Chansons de Geste, thus, present a fictional playing field where medieval anxieties over miscegenation are revealed and resolved.

Anxieties over biological inheritance is apparent not only in literature but also in the laws of the Fourth Lateran Council, 1215. Canon 50, for example, prohibits marriages to the fourth degree of kinship. The reason provided for this restriction is a biological one: “The number four agrees well with the prohibition concerning bodily union about which the Apostle says, that the husband does not rule over his body, but the wife does; and the wife does not rule over her body, but the husband does; for there are four humours in the body, which is composed of the four elements.”[vi] But, it is not merely biological inheritance that is addressed in the Fourth Lateran Council. Canon 68 discloses concerns about impurity incurred due to intermixing. This Canon mandates that Jews and Saracens should dress differently from Christians:

A difference of dress distinguishes Jews or Saracens from Christians in some provinces, but in others a certain confusion has developed so that they are indistinguishable. Whence it sometimes happens that by mistake Christians join with Jewish or Saracen women, and Jews or Saracens with Christian women. In order that the offence of such a damnable mixing may not spread further, under the excuse of a mistake of this kind, we decree that such persons of either sex, in every Christian province and at all times, are to be distinguished in public from other people by the character of their dress.[vii]

This decree suggests that it was difficult to distinguish between Christians and non-Christians which allows for free mixing between the two groups. While this Canon expresses the concern that uninhibited ‘mixings’ often led to sexual relations, it might also reveal apprehension about the exchange of ideas and practices between Christians and non-Christians. Hence the insistence that other religious communities dress differently so as to contain all types of mingling or at the very least make such interactions in plain view and, by extension, manageable.

The apprehension over exchange of ideas and practices is obvious in Canon 70, which prohibits new converts from retaining any remnants of their old faith: “Certain people who have come voluntarily to the waters of sacred baptism, as we learnt, do not wholly cast off the old person in order to put on the new more perfectly. For, in keeping remnants of their former rite, they upset the decorum of the Christian religion by such a mixing.”[viii] This canon points to a phenomenon that was probably occurring in Christendom, that is, of non-Christians converting to Christianity as a means to achieve goals other than a genuine acceptance of a new faith and, therefore, converts did not necessarily shed the customs and traditions of their previous faith. Moreover, even if there was genuine intent, a combination of factors such as habit, comfort, and social pressure may have caused them to revert to the practices of their former tradition. The problem that the Canon addresses is not a biological one, but that of maintaining religious decorum while receiving converts from other faiths and traditions.

Literature in Western Christendom reveals an anxiety about biological inheritance in a mixed marriage. These anxieties appear to stem from the idea that religion was inheritable. Along the same lines, these poems permit assimilation of only those Muslims who fulfil Christian standards of beauty. In other words, in order for the Muslim to be assimilated, he or she should either already have the physical attributes of a “Christian” or conform to those attributes upon baptism. Biological inheritance is a concern in the Fourth Lateran Council of 1215 as well. However, the principal focus of these decrees is the maintenance of religious homogeneity and decorum.

The most fascinating feature about the study of medieval miscegenation is the extent to which these negative yet complex attitudes persist in the modern world. Clearly, even today there is unease and concern about marrying a person of a different race or culture. While the idea of having sexual relations outside racial categories may sound appealing, the extent of difference—physical or otherwise—that individuals are willing to tolerate may not be substantial enough to allow such relationships to succeed. Whether it is sexual purity or biological inheritance or religious decorum that was the concern during the Crusades or whether it is the extent of difference individuals tolerate in modern day culture, miscegenation stirred and continues to stir complex attitudes in ancient and medieval as well as modern societies.

Ambika Natarajan

Visiting Lecturer and Research Associate

UM-DAE Centre for Excellence in Basic Sciences

To learn more about her research, visit her website: https://ambikasana.com/

[i] Lynn Ramey, Christian, Saracen and Genre in Medieval French Literature (New York: Routledge, 2001).

[ii] Lynn Ramey, “Medieval Miscegenation: Hybridity and the Anxiety of Inheritance,” in Contextualizing the Muslim Other in Medieval Christian Discourse, ed. Jerold C. Frakes (New York: Palgrave Macmillan 2011), 1-20.

[iii] “The Capture of Orange,” in Heroines of the French Epic: A Second Selection of Chansons de Geste, trans. Michael Newth (Hungerford: D.S Brewer, 2014), 17.

[iv] “Aye of Avignon,” in Heroines, 188.

[v] Lynn Ramey, Christian, Saracen and Genre, 65.

[vi] Canon 50, J. Schroeder, “Fourth Lateran Council, 1215,” in Disciplinary Decrees of the General Councils: Text, Translation and Commentary (St. Louis: B. Herder, 1937), 236-296.

[vii] Canon 68, J. Schroeder, “Fourth Lateran Council, 1215,” in Disciplinary Decrees, 236-296.

[viii] Canon 70, J. Schroeder, “Fourth Lateran Council, 1215,” in Disciplinary Decrees, 236-296.