As an integral part of the Church ritual, liturgical hymns provide what is possibly the most effective means of communicating dogmatic truths and conveying ethical ideals to the congregation. Combining words and music, hymns can produce a strong impression upon the minds of the faithful and play an important role in their spiritual edification. However, it would not be correct to assume that their content is exclusively spiritual. Rather, due to a specific relationship between the state and the church in the Eastern Roman Empire, better known as Byzantium (330-1453), it is not surprising that liturgical hymns contain many references to the emperor. In the aftermath of the legalisation of Christianity with the issuance of the Edict of Milan in 313 CE, and especially when Christianity became the official religion of the Roman Empire in 380 CE, the liturgy was regularly used to support imperial authority.

The promulgation of the Edict of Milan and the conversion of the emperor Constantine the Great (d. 337) to Christianity completely changed the position of the Church in the empire. After a period of persecutions, the Church became the second most important pillar of society, with the imperial power being the first. Especially important for the construction of this new reality was the production of the discourse surrounding Constantine’s conversion. This discourse was based on the cross, the supreme Christian symbol, and on several prominent Old Testament leaders of the chosen people, especially Moses, David, and later Joshua. The contribution of Eusebius (d. 339), sometimes characterised as “court theologian,” to the creation and dissemination of this discourse was enormous, and this laid the foundation for what would be later known as a ‘symphony’ or the harmonious coexistence of state and church.

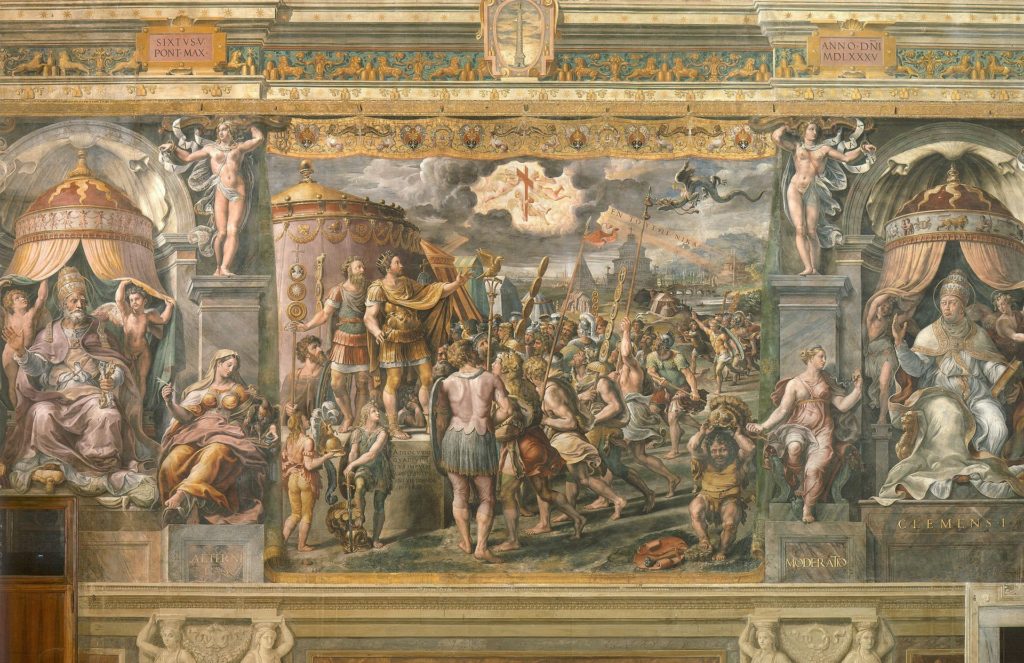

The cross, initially understood as a symbol of Christ’s victory over the Devil and death, became closely related to the emperor and transformed into a symbol of imperial victories and prosperity of the empire with divine assistance after Constantine’s victory under that sign against Maxentius (Eusebius, VC 1.27-39).

This idea, after being developed in various literary genres, especially panegyrics, found its way into liturgical hymns. Hymnographers frequently eulogise the cross as a powerful weapon, which brings victories to the emperor and secures peace in the empire. Liturgical hymns for the Exaltation of the True Cross (14 September), the central annual feast of the cross in the Byzantine tradition, repeatedly stress not only the spiritual dimension of the cross in Christian life but also its military and triumphant functions. The best example is probably the apolytikion, as the main celebratory hymn for each feast is called, for the feast of the Exaltation: “O Lord, save your people and bless your inheritance, grant victory to the emperor against the barbarians, and guard your empire through your cross” (Festal Menaion, September 14). The hymn strongly emphasises the close interrelation between the cross, the empire and the church community. The community prays to God to save and protect the subjects of the empire through his cross, which secures imperial victories against the barbarian enemies (cf. Demacopoulos, 123). Similar references to the cross abound in hymns for this feast. However, for this occasion I will include only two more examples, both taken from an unpublished hymn attributed to Germanos I, Patriarch of Constantinople (d. 740), and preserved in an eleventh-century manuscript from the collection of Mount Sinai. The first one reads as follows:

“We pray, grant to the most pious emperor your power, through your life-giving cross, O Christ; he boasts about you and, placing his hopes in you, will be saved.”

Sinait. gr. 552, f. 129

In the second one, the invocation of the cross’s might is not phrased in generic terms; rather, the hymnographer makes specific references to the power of the cross against the Arab Muslims.

“Let us bow before the wood of the Cross, which provides the power to the most pious emperor against enemies, and subjects to him the foolish offspring of Hagar.”

Sinait. gr. 552, f. 128v

The cited example shows how a reference to the cross becomes part of inter-religious polemics. The author praises the cross as a source of power for the emperor to defeat his foes who are denoted as descendants of Hagar. The word “Hagarenes”, designating the offspring of Abraham’s slave Hagar in its biblical usage (Gen. 16; Chr. 5:19, and Ps. 82:7), was commonly employed by Christian authors to denote the Arabs both before and after the appearance of Islam, as they were believed to be the offshoot of Hagar’s son Ishmael.

In Byzantium, the emperor was also frequently related to distinguished Old Testament figures, especially to prominent leaders of the Israelites. Byzantine rhetorical treatises, such as the tenth-century On the Eight Parts of Rhetorical Speech, provide clear instructions to panegyrists to compare the emperor with Moses, David and Joshua the son of Nun. This practice gradually found its way to liturgical hymns. The aforementioned manuscript from the Mount Sinai collection transmits a hymn for the annual celebration of Joshua the son of Nun. Intriguingly, in the Christian tradition of the first millennium, Joshua was rarely regarded as a model warrior or related to the emperor. This perception changed from the ninth century onwards, especially at the time when Byzantine emperors attempted to recapture Palestine from the Arabs.

Having as the point of departure Joshua’s accomplishments and military exploits against the Amalekites, and especially the narrative that he led the Israelites into the Promised Land (Joshua 3:1-14), the author of the hymn from the Sinai manuscript puts Joshua’s leadership and military exploits in the foreground, directly associating him with the emperor. Thus in one of the stanzas, the poet appeals to God as follows:

“You who were fellow-general of your servant Joshua against his opponents in the past, now in a similar way be fellow-general of the emperors against [their] enemies.”

Sinait. gr. 552, f. 11

There is little doubt that this and other references to Joshua need to be seen within the broader historical context of the Middle Byzantine period, especially in relation to the Byzantine-Arab wars during the reign of the emperors from the Macedonian dynasty (867-1056) who sought to return Palestine to Byzantine control. Joshua’s leadership skills and military prowess, which he demonstrated in warfare against the native population of the Promised Land, became a source of inspiration for Byzantine authors and artists during the same period. As a result, visual representations of Joshua appear with some frequency in monumental painting and on portable objects produced during the so-called Macedonian Renaissance.

Hymnographic texts, addressed to a wide audience, could also be effectively mobilised to reinforce imperial authority among imperial subjects. Even more so when a good opportunity was available, as in the present case, namely on the feast day of one of the most prominent leaders of God’s chosen people. Since the Byzantines regarded themselves as the New Israel, with the pious emperor as their leader comparable to the Old Testament leaders, the author of the kanon exploited this to relate the emperor to Joshua. In this respect, the hymn can be compared to other genres of Byzantine literature whose main purpose was to glorify the emperor.

As a conclusion, it can be said that the New Testament commandment to pray for those in power (1 Tim 2: 1-2) from the time of Constantine developed into the concept that the emperor is the chief protector of the church and orthodoxy and has to be glorified in liturgy. In addition, imperial success in wars against those of a different religion was understood as a guarantee for the freedom of the Christian faith in the empire. Moreover, by comparing the warfare between the Eastern Roman Empire and their enemies, particularly against the Persians and Arabs, with the wars that the biblical chosen people of ancient Israel waged against the Amalekites, Byzantine authors situated those wars within the biblical context attaching a sacred character to them. In that way, the Byzantines became the New Israel, and their emperors were understood as the successors of the Israelite leaders. Consequently, their inclusion in liturgical texts and the ritual was considered legitimate.

Kosta Simic

Byzantine Postdoctoral Fellow, Medieval Institute

University of Notre Dame (2021-2022)

Further Reading:

Eusebios, Eusebius Werke I. Über das Leben Constantins. Constantins Rede an die Heilige Versammlung. Tricennatsrede an Constantin, GCS 7, edited by I. A. Heikel, Leipzig: J. C. Hinrichs’sche Buchhandlung, 1902. English translation: Life of Constantine, trans. A. Cameron and S. Hall, Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1999.

Demacopoulos, George. “The Eusebian Valorization of Violence and Constantine’s Wars for God”. In Constantine: Religious Faith and Imperial Policy, edited by Edward Siecienski, 115-128. London: Routledge, 2017.

Schapiro, Meyer. “The Place of the Joshua Roll in Byzantine History,” Gazette des beaux-arts 35 (1949) 161–176.

Rapp, Claudia. “Old Testament Models for Emperors in Early Byzantium”. In The Old Testament in Byzantium, edited by P. Magdalino and R. Nelson, 175-197. Washington: Dumbarton Oaks Research Library and Collections, 2010.

Simic, Kosta. “Remembering the Damned. Byzantine Liturgical Hymns as Instruments of Religious Polemics”. In Memories of Utopia: The Revision of Histories and Landscapes in Late Antiquity, edited by Bronwen Neil and Kosta Simic, 156-170. London: Routledge, 2020.

The Festal Menaion, trans. Mother Mary and Archimandrite Kallistos Ware, London: Faber and Faber, 1969.

Thierry, Nicole. “Le culte de la croix dans l’empire byzantine du VIIe siècle au Xe dans les rapports avec la guerre contre l’infidèle”. Rivista di studi bizantini e slavi 1 (1980/81) 205-228.