Contemporary monsters associated with modern Halloween celebrations—such as vampires, werewolves and mummies—borrow heavily from the genre of Gothic Horror which takes shape during the early modern period in the hands of Romantic and Victorian authors.

Indeed, Gothic Horror, the literary source of many monsters commonly associated today with Halloween, regularly draws inspiration from the medieval period. Authors from Mary Shelley to Edgar Allen Poe capitalize on the haunting way the past is often reimagined in the present as mysterious, unknown and full of terrors. This year’s Halloween special, in celebration of Samhain and All Hallows Eve, considers the characterization of one famous medieval monster sometimes associated with the modern concept of “the vampire” in popular culture.

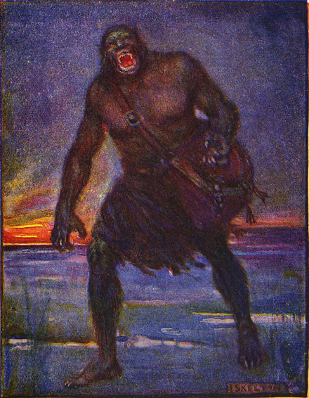

One of the most well-known monsters from the Middle Ages, Grendel, the terrifying cannibal from Beowulf, is frequently regarded as a medieval vampire in contemporary vampire lore, despite that the Old English poem seems not to have been readily available during the Victorian period. Although, Beowulf was first transcribed in 1786, with an edition later printed in 1815 by Grímur Jónsson Thorkelin who also translated the poem into Latin, its influence remained obscure. Some verses from Beowulf were translated into modern English in 1805, and nine complete translations were produced in the 19th century, including one by William Morris, but it was only after the turn of the 20th century that an abundance of translations became available making Beowulf accessible to public audiences and leading to growing interest in the Old English poem during the period which helps establish Beowulf as central to English literary canons thereafter.

Nevertheless, when Lord Byron, John Polidori, John Stag and Bram Stoker were contributing to the development of tropes and stereotypes that inform modern representations of vampires, they self-consciously and explicitly looked to the past “dark ages” with a macabre, antiquarian eye. Often, these authors will cite unspecified ancient lore and legend in an attempt to ground their vampire literature in a mythologically (if not historically) authenticated past in which monsters and magic are possible. These possibilities, then, extend into the present as gothic monsters reach from the deep recesses of time into modern times so that they may haunt the living. Vampires like many gothic monsters are generally understood as an anachronism, able to exist now only because they existed then, thereby suspending modern sensibilities and skepticisms. Indeed, the longstanding affiliation between medieval corpses and modern vampires is mobilized in a recent blog centered on vampirism, succubi and women’s monstrosity.

Each of these Victorian authors reach to the medieval period in order to craft their modern undead monsters, sometimes even looking toward historical figures, such as Vlad III of Wallachia (better known as Vlad “the Impaler”) as an inspiration for Bram Stoker’s Dracula. Of course, it seems that none would have borrowed directly from the Old English poem.

So why is Grendel considered a vampire? Is there any textual evidence to support this claim?

While Grendel’s monstrosity remains mysterious, and some might see little resemblance between the medieval monster and Victorian vampires, there is one passage centered on Grendel’s cannibalism, which serves as a major source for Grendel’s association with vampirism. The section reads as follows:

Geseah he in recede rinca manige,

swefan sibbegedriht samod ætgædere,

magorinca heap. Þa his mod ahlog;

mynte þæt he gedælde, ærþon dæg cwome,

atol aglæca, anra gehwylces

lif wið lice, þa him alumpen wæs

wistfylle wen. Ne wæs þæt wyrd þa gen

þæt he ma moste manna cynnes

ðicgean ofer þa niht. Þryðswyð beheold

mæg Higelaces, hu se manscaða

under færgripum gefaran wolde.

Ne þæt se aglæca yldan þohte,

ac he gefeng hraðe forman siðe

slæpendne rinc, slat unwearnum,

bat banlocan, blod edrum dranc,

synsnædum swealh; sona hæfde

unlyfigendes eal gefeormod,

fet ond folma.

“He [Grendel] saw in the hall many warriors, the troop of kinsfolk slept, gathered together, a heap of kindred warriors. Then his mind laughed, because he, the terrible, fearsome marauder, intended to rend life from the body of every one of them before day came, when the expectation of gluttony came over him. It was nevermore his fate that he might eat more of mankind over the night. The very mighty kinsman of Hygelac beheld how the criminal destroyer would fare with its sudden grips. The fearsome marauder did not think to delay, but he quickly seized a sleeping man the first time, tore ravenously, bit his bone-locker, drank the blood from his veins, swallowed the sinful morsel; soon he had finished off all of him, unliving, feet and hands” (728-745).

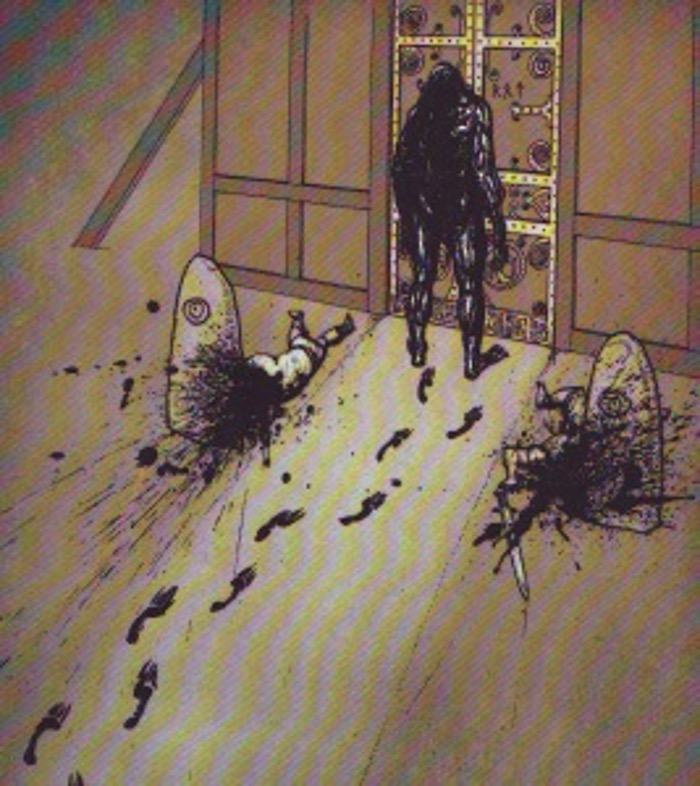

Most often, emphasis is placed on Grendel’s cannibalism and specifically his consumption of flesh mentioned in the passage. Few modern adaptations of Beowulf—from Michael Crichton’s Eater of the Dead (1976) to John Tiernan’s The 13th Warrior (1999) based on Crichton’s adaptation to Sturla Gunnarsson’s Beowulf & Grendel (2005), Robert Zemeckis’ Beowulf (2007), or even Cartoon Network’s adaptation of the poem in Adventure Time’s “The Wild Hunt” (2018)—depict Grendel as especially fond of blod edrum drincan “drinking blood from veins” (742), despite that the poem describes this vampiric act in gory detail.

Although most Beowulf adaptations focus more attention on flesh-eating than on blood-drinking, parallels between vampires and Grendel have not gone unnoticed, and categorizations of vampire-types sometimes include a Grendelish category, as demonstrated by the ferocious and bestial Gangrel, known for being especially close the “the Beast” within, their association with medieval Scandinavia and their ravenous consumption of blood in the popular roleplaying game, Vampire: The Masquerade. Moreover, Cain’s association with vampirism often mirrors his role as progenitor of the Grendelkin and all monsterkind in Beowulf.

Grendel may not be a proper vampire in the technical, stereotypical, modern understanding of the term. Moreover, Grendel’s characterization in Beowulf apparently did not affect vampire stereotypes developed in the early modern period before knowledge of the Old English poem became mainstream. Nevertheless, the graphic image of the monster haunting at night, coming from the darkness, perhaps shapeshifting from a shadow to human form, and most importantly, sucking the blood from the veins of his victim, marks Grendel’s characterization as eerily close in certain aspects to modern vampires, who share his love of darkness, often possess shapeshifting abilities and likewise glut themselves on human blood.

Richard Fahey, Ph.D.

Medieval Institute

University of Notre Dame