Beowulf is a story about a doomed people who are destined for annihilation as a result of depredation, feuding, and cyclical inter-tribal violence. Yet, the violence described in the poem is not always outward but often occurs from within, as acts of intra-tribal violence frame much of the narrative. Even seemingly positive events are thus generally short-lived. Accordingly, in the eminence of King Hrothgar’s glorious construction of Heort, the narrator reveals the hall’s imminent doom:

Sele hlifade

heah ond horn-geap. Heaðo-wylma bad

laðan liges. Ne wæs hit lenge þa gen

þæt se ecg-hete aþum swerian

æfter wæl-niðe wæcnan scolde. (81-5)

The hall sheared upward, high and horn-vaulted. For the battle-surge it waited, loathsome fire. Nor was it long before the edge hate of aþum swerian must awaken for slaughter-spite.

Beowulf Manuscript, excerpt with aþum swerian.” BL, Cotton Vitellius a.vx. MS 130v, BL 133v.

This dire prediction identifies the causal agents of disaster as aþum-swerian. But given that this term is unattested and grammatically invalid, we are bound to ask: Who are these aþum-swerian? The conventional approach solves this conundrum by creating a new term in imitation of such copulatives as suhtergefaedaran (“nephew and uncle” from Beowulf), gisunfader (“son and father” from Heliand), and sunufatarungo (“son and father” from Hildebrandslied). Following these models, the editors of Klaeber 4 (120, 350, 437) emend the term to aþum-sweoran, thereby conjoining aþum (sons-in-law) and sweoran (fathers-in-law). Because this solution apparently predicts the sundering of vows between Ingeld and Hrothgar (2022-66), this emendation has become the dominant convention.

Nevertheless, there are problems. First, the emended term, glossed as “sons-in-law and fathers-in-law,” differs markedly from the models, which are glossed as “nephew and uncle” and “son and father.” And though the term aþ is indeed attested with the gloss “son-in-law,” the rendering aþum-sweoran is a hapax legomenon attested nowhere in the extant corpus of Old English literature. Making the invention yet more suspect is the well-attested phrase, sweor ond aþum (father-in-law and son-in-law), which would seem to preclude a need for the copulative.

The proposed term also falls short in its narratological salience. There are no “sons-in-law” implicated in the violence that erupts at Ingeld’s wedding, only one “son-in-law.” Yet more problematic, this single crisis cannot account for the apocalyptic imagery that frames Heorot’s catastrophe. Prior to the prediction of calamity, the hall’s construction is marked by an array of tropes that suggest the Tower of Babel. As Tristan Major observes, “Hrothgar’s rise to power [64-79] and the building of his hall, Heorot, echoes Nimrod and the Tower of Babel” (242).” Likewise, as Daniel Anlezark observes, the hall’s destruction is marked by retributive images of Flood and Hellfire (336-7). In sum, the proposed solution leaves important problems unresolved. It inaccurately predicts “sons-in-law” in respect to Ingeld. And it does not account for the apocalyptic imagery of idolatry, flame, and fire that marks Heorot’s doom.

The Tower of Babel. London, British Library, Cotton Claudius B.IV, fol 19r.

In this review, we promote an alternative initially proposed by Michael Alexander. This alternative interprets aþum as the plural dative “oaths” and emends swerian to the plural dative -swaran (swearers). The rendering “swearers of oaths,” acknowledged by Klaeber 4 as possible, has the advantage of relying on attested terms. The plural dative form aþum (oaths) occurs not only in the corpus but also in Beowulf, and the second term (-swara) occurs in a similar compound, man-swaran (criminal swearers). Yet more support for this construct can be found in the oath-swearing between Hengest and Finn. Here the term aðum also occurs as a plural dative, framing a parallel scenario in which oaths will be broken and a hall destroyed:

Fin Hengeste

elne, unflitme aðum benemde

þæt he þa wealafe weotena dome

arum heolde, þæt ðær ænig mon

wordum ne worcum wære ne bræce . . . . (1097-100)

“Fin with Hengest without quarrel declared his oath that he would by his council’s judgment hold [the truce] with honor that any man there by word or deeds should not break the covenant . . . .”

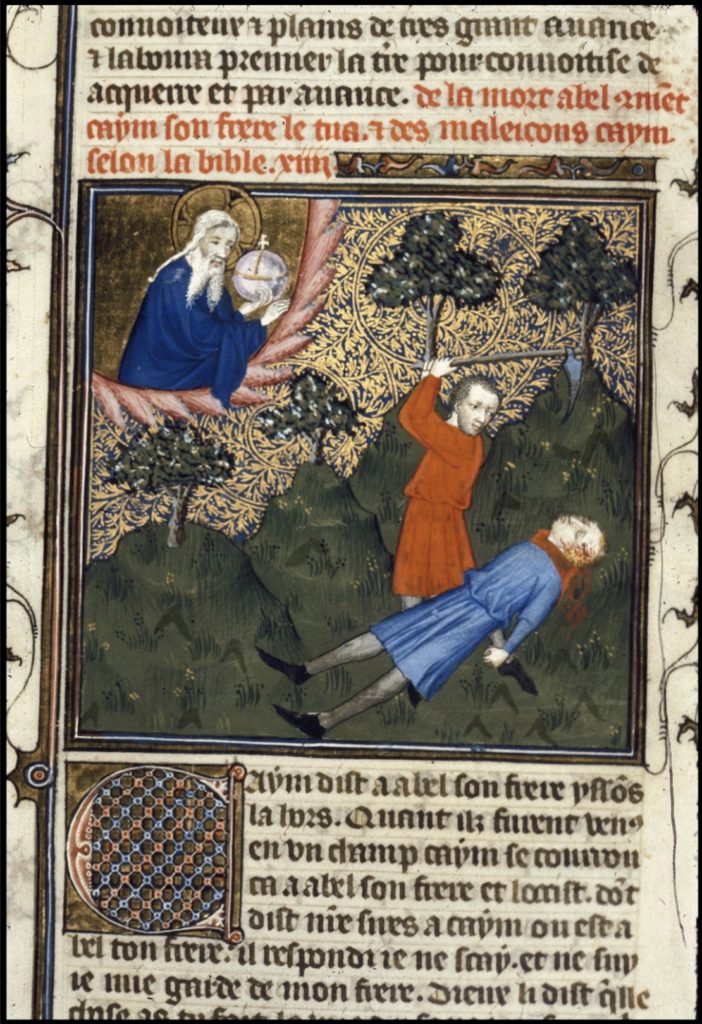

The emendation to aþum-swaran also offers much stronger alignment with the narrative arc. Notably, this alignment begins with the paired disclosures that define Fitt I: Whereas the history of Grendel’s origin locates Cain’s act of murder as a calamity in the past, the prediction of murderous oath-swearers locates Heorot’s destruction as a calamity in the future. This parallel design is highly significant: In effect, it forges a link between Cain’s crime of kinship murder and the internecine violence that spells Heorot’s doom. This linkage, moreover, not only intimates the Danes’ ongoing state of iniquity but also explains the apocalyptic tropes that frame the hall’s calamity. Accordingly, Heorot’s doom emerges not as a circumstantial event caused by brawling Danes and Heathobards but as an in-kind retributive event that aligns perfidious Nordic warriors with the curse of exile from human joys, entailed in Cain’s crime and punishment.

Notably, also, the intimation of Danish perfidy is borne out across the narrative arc. Beowulf and the narrator declare Unferth’s fratricidal treachery; the narrator insinuates Hrothulf’s possible resentment against his uncle, Hrothgar; the lay of Finn and Hildeburh recounts the Danes’ violation of peace oaths in favor of murderous revenge; Hrothgar’s adoption of Beowulf sparks Wealhtheow’s resistance and her appeals to warriors in the hall; and Hrothgar violates his promise of protection to the Geats, potentially inciting Beowulf’s revenge. This surfeit of Danish treachery, in other words, aligns perfectly with the narrator’s revelation that “swearers of oaths” will soon incite violence.

For this reason, also, the reference to oath-swearers functions as a formula for suspense—a design that impels the audience to consider, in a fictive world replete with perfidy and oath-making, which of the oath-swearers will incite a conflagration? Will Unferth the fratricide murder again? Will Hrothulf avenge his displacement from the throne? Will one of the Danes retaliate against Hrothgar’s covenant with Beowulf, the foreigner? Will Wealhtheow incite the same kind of intertribal violence that erupts in the Frisians’ hall? Will Beowulf retaliate against Hrothgar for deserting his men?

The emendation to aþum-swaran presents a solution that is better attested and more meaningful than the conventional emendation to aþum-sweoran. As noted above, the gloss of “sons-in-law” does not possess predictive value regarding Ingeld, and the sundering of vows between Ingeld and Hrothgar cannot explain the apocalyptic imagery surrounding the disclosure of Heorot’s doom. Conversely, that same apocalyptic imagery aligns perfectly with a depiction of Danish society as inherently unstable, doomed to self-destruction, as the unchecked impulses of egoistic aggrandizement overcome the covenants that bind social order. Likewise, the depiction of Danish perfidy permeates the narrative arc. Accordingly, the disclosure of violent oath-swearers functions within an ingenious narrative design. It affords the schadenfreude of dramatic irony, as the audience anticipates a disaster the characters know not of. And it thus generates a game of blind corners, in which the audience’s knowledge of impending violence from oath-swearers charges subsequent events with anticipation and suspense.

Chris Vinsonhaler & Richard Fahey

Medieval Institute

CUNY University & University of Notre Dame

Selected Bibliography & Further Reading

Alexander, Michael. Beowulf: A Glossed Text. Penguin Classics, 1995.

Anlezark, Daniel. Water and Fire: The Myth of the Flood in Anglo-Saxon England. Manchester U Press, 2006.

Major, Tristan. Undoing Babel: The Tower of Babel in Anglo-Saxon Literature. U Toronto Press, 2018.