From the start of the First Crusade, Christian men were fascinated with the possibility of marrying Muslim women. In his account of the Battle of Antioch (1097-1098), Peter of Tudebode narrates an incident about the Emir, Yaghi Siyan, offering the Crusaders the following bargain: “Deny your God, whom you worship and believe, and accept Mohammed and our other gods. If you do so we shall give to you all that you desire such as gold, horses, mules, and many other worldly goods which you wish, as well as wives and inheritances; and we shall enrich you with great lands” (pp. 58-59). The bargain included wives.

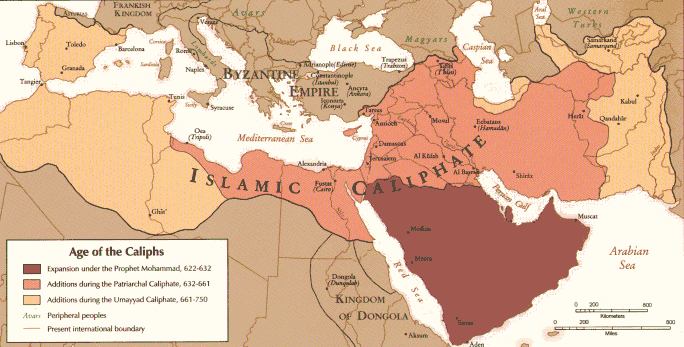

Fulcher of Chartres’s utopian version of the intercultural interaction reads like a propaganda piece meant to attract prospective settlers to the newly established Crusader territories. He provides an idyllic vision of assimilation that took place at the meeting point of the East and the West. According to him, assimilation was achieved through the acquisition of inheritable properties and servants by Occidentals, the mutual blending of languages, and most importantly through intermarriages between Christian men and non-Christian women through baptism as he boasts, “Some have taken wives not merely of their own people, but Syrians, or Armenians, or even Saracens [medieval term for Muslims] who have received the grace of baptism” (p. 281). Fulcher’s account, written around 1125 appeals to the aspirations of prospective male settlers in Western Christendom—their aspirations for property and wives. The two examples provided above, resist a simplistic version of what happened between Christians and Muslims during the Crusades. Popular portrayals suggest that the Crusades were violent religious conflicts in the Middle Ages with Christianity on one side and Islam on the other.

However, violence is only one part of the story. Relations between these two religious groups were much more complex. The writings of both Fulcher and Tudebode suggest that the idea of securing local wives was tempting to the Crusaders and the settlers of newly acquired territories. The Crusades reveal that medieval attitudes towards sexuality were not always rigid and repressed.

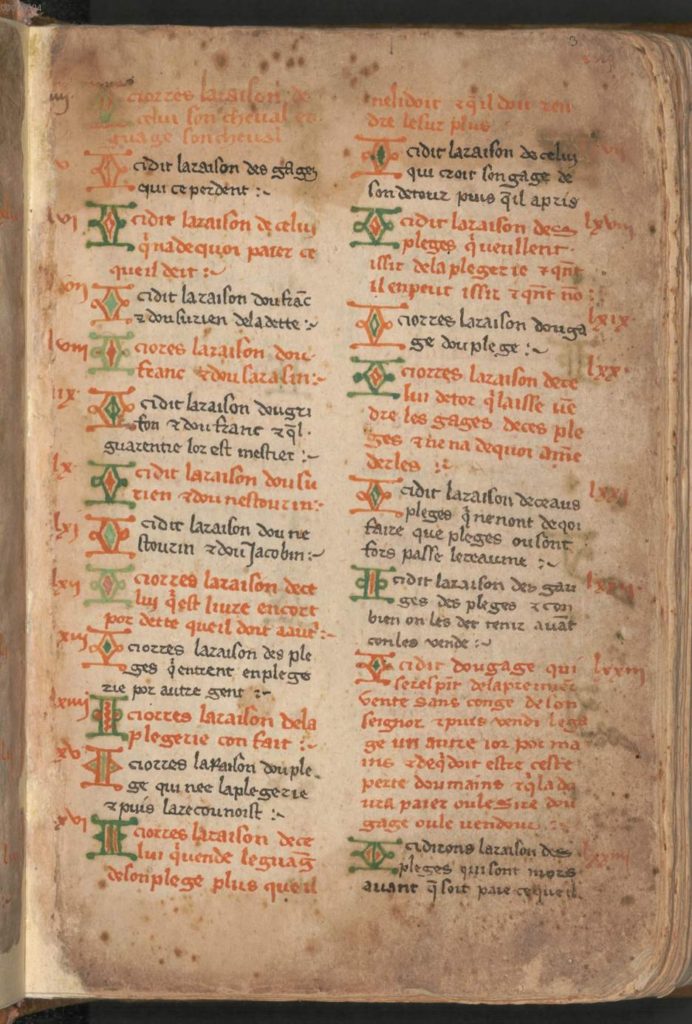

Even though the earliest laws in the Crusader states reveal concerns about the danger miscegenation posed to Christian sexual purity, they focus on sexual acts and do not explicitly forbid interfaith marriages. The Canons of the Council of Nablus of 1120, the earliest laws in the Latin Kingdom of Jerusalem prescribed draconian measures against the rape of Muslim slave-women by Christian men. Canons 13 and 14 punished sexual activity between Christian men and Muslim slave-women with castration and expulsion. In the same vein, Canon 15 of the Nablus prohibits consensual sex between Muslim men and Christian women. Thus, these Canons reveal an anxiety about intermixing and the impurity incurred by sexual acts between Christians and Muslims.

However, the Nablus laws were not concerned about interfaith marriage. Marriages between Christians and non-Christians (pagans, Muslims and Jews) were quite common in the initial stages of the Crusades. In fact, there is no law in the Nablus that prohibits consensual or non-consensual sex between Christian men and free Muslim women. There are two possible reasons for this: either every single Muslim woman was enslaved once Jerusalem was captured during the First Crusade or sexual acts between Christian men and free Muslim women were not considered threats to sexual purity.

The conspicuous absence of a law prohibiting sexual acts between Christian men and free Muslim women silently condones the Christian penetration of Muslim culture and, hence, the latter’s subordination through sexual acts with free Muslim women; just as Canon 15 prevents the Muslim subordination of Christians by prohibiting sex between Christian women and Muslim men. The Nablus laws reveal a nuance in how the idea of sexual purity worked in the Crusader states. In a master-slave dynamic, when the Muslim was already in a subordinated state, the fact that she was Muslim was important. A Christian man having sex with a Muslim slave constituted sexual impurity. However, when the Muslim woman was free, the dynamic was dramatically altered. The focus then was on the fact that the Muslim is free, suggesting that a member of an antagonistic religious group had autonomy. The existence of a free Muslim presented evidence that complete subordination of the community was not achieved. Consequently, sex with a free Muslim woman did not constitute impurity. Rather it was an act of nullifying the autonomy of the Muslim community through religious conquest disguised as sexual penetration.

Thus, the laws pertaining to sex and marriage in Crusader states evolved with the evolving necessities and concerns in Western Christendom. At the start of the First Crusade, the exertion of Christian dominance over Muslim subjects entailed sexual acts and marriage between Christian men and free Muslim women as suggested by Nablus laws. By the mid-thirteenth century, intermixing was increasingly prohibited for economic reasons.

Ambika Natarajan

Oregon State University

Ambika Natarajan received her Ph.D. in the History of Science from Oregon State University and she specializes in the History of Science and Sexuality in the Habsburg Monarchy. Her research work focuses on multiple aspects of migrant female work, including domestic work and sex work and how working-class women altered the discourse on labor and migration. Her work has appeared in The Austrian History Yearbook and she is currently working on a book manuscript. She also has graduate degrees in English Literature and Biotechnology and diplomas in German, French, and Creative Writing and has taught courses in Biostatistics and graduate-level biology courses, Russian History, American Diplomatic and Religious History, and History of Science and Religion internationally.

To continue reading about the complex intersection of race and religion in sexual relations between medieval Muslims and Christian during and after the Crusades, see her subsequent blog on the subject.

To learn more about her research, visit her website.