If you and I were to go for a stroll through the streets of London—let’s say, one summer afternoon in 1392—what kinds of sounds would we hear?

According to William Langland’s late fourteenth-century poem Piers Plowman, we might hear a cacophony of street cries including the shouts of cooks and tavern-keepers: “Hote pyes, hote! / Goode gees and grys! Ga we dyne, ga we!” (Prol. 228-35). (Incidentally, London’s street cries have been featured in musical compositions from Renaissance madrigals to twentieth-century composer Luciano Berio’s “Cries of London.”) But if we happened to be in London at just the right moment, we might hear something remarkable—the arresting sounds of a procession.

A procession–broadly defined as a group of individuals moving along a specific route to a certain destination–would capture our attention in numerous ways. As Kathleen Ashley has written, processions offered a “fusion of sensory experiences, or synaesthesia” (13). Indeed, they were both visually compelling, featuring canopies, torches, reliquaries, crosses, and flowers, and also aurally compelling, with singing voices, ringing bells, and the sounds of lutes, drums, and cymbals.

London would have seen many different kinds of processions—all of them with distinctive sounds. There would be royal processions creating an atmosphere of splendor and pomp.

Often (as in the image below) musicians would accompany these regal processions, and sometimes dancers would also perform.

Religious processions would also pass through the streets, celebrating various holy days (e.g., Christmas, Easter, and Corpus Christi). These often featured ringing bells and chanting voices, and such sounds were thought to ward off demons and elicit divine grace.

Of course there were funeral processions, where corpses were carried through the streets as mourners wailed and bells tolled–undoubtedly an almost constant sound during the time of the plague. As the popular medieval philosopher Boethius wrote, “The cause for weeping might be made sweeter through song” (8).

Like Langland, Chaucer infuses his writing with the sounds he experienced in London, and in the Prioress’s Tale, he specifically incorporates the sounds of processions.

In the beginning of the story, the clergeon sings the antiphon Alma redemptoris mater as he walks to school and back home: “Ful murily than wolde he synge and crie” (553). It is a kind of solo procession.

[iframe width=”560″ height=”315″ src=”https://www.youtube.com/embed/kIXNIZxXwoI” frameborder=”0″ allowfullscreen]

Later, we find a foreshadowing of the clergeon joining a heavenly procession of virgin martyrs where he will follow “The white Lamb celestial” and “synge a song al newe” (581, 584).

Towards the end, the clergeon’s body is carried through the streets to the abbey “with honour of greet processioun” (623). Miraculously, he continues to sing the Alma, serving as the musician at his own funeral.

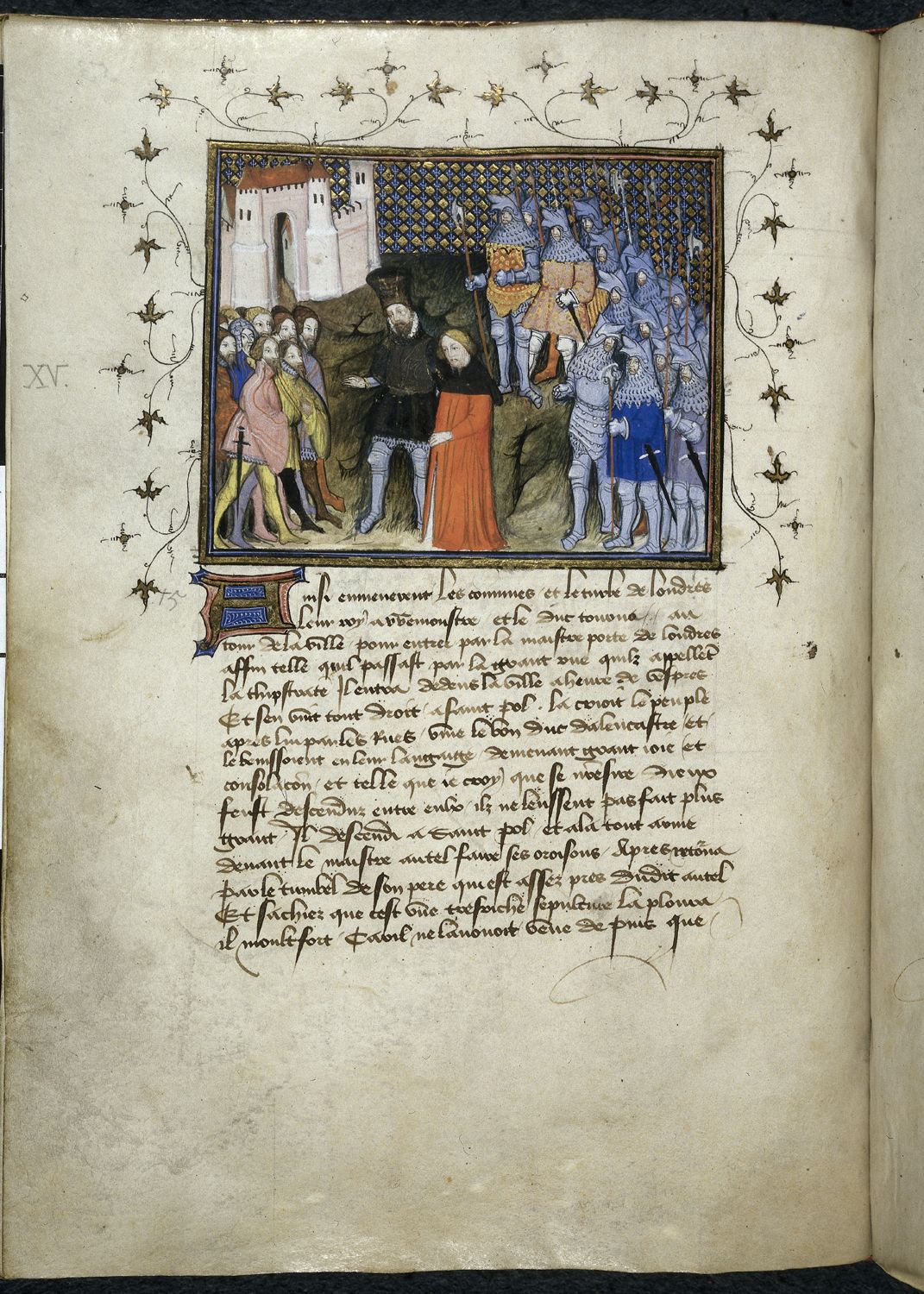

It seems fitting that such a series of processions should take center stage in the Prioress’s Tale since the Prioress herself would have come from a nunnery where processions formed a significant part of life. In fact, we have medieval documents (e.g., the Barking Ordinal) that provide instructions for nunnery processions. As the image below suggests, these processions would have been aurally compelling. Notice the one nun pulling the bell rope and the others singing from books with musical notation.

We can add a new dimension to our understanding of life in the Middle Ages by reconstructing some of the sounds of the streets of medieval London. Such sounds have not altogether died away. In closing, here is a performance from the 2015 Mummer’s Parade in Philadelphia — a parade with roots reportedly dating back to the Early Modern period.

[iframe width=”560″ height=”315″ src=”https://www.youtube.com/embed/n0w0MiATTF8″ frameborder=”0″ allowfullscreen]

Ingrid Pierce

PhD Candidate

Department of English

Purdue University

Sources

Ashley, Kathleen and Wim Hüsken. Moving Subjects: Processional Performance in the Middle Ages and the Renaissance. Amsterdam, Atlanta: Rodopi, 2001.

Chaucer, Geoffrey. The Wadsworth Chaucer, formerly The Riverside Chaucer. 3rd ed.

Ed. Larry D. Benson. Boston: Wadsworth, 1987.

Langland, William. Piers Plowman: A New Annotated Edition of the C-text. Edited by

Derek Pearsall. Liverpool: Liverpool University Press, 2008.

Reynolds, Roger. “The Drama of Medieval Liturgical Processions.” Revue de Musicologie 86.1 (200): 127-42.

Yardley, Anne Bagnall. Performing Piety: Musical Culture in Medieval

English Nunneries. New York: Palgrave, 2006.