As thousands of scholars make our pilgrimage to the 52nd annual meeting of the International Congress on Medieval Studies at Western Michigan University in Kalamazoo (known to many affectionately as “the ‘Zoo”) we look forward to the largest gathering of medievalists in North America. Over the course of yesterday (Thursday) through this Sunday, many scholars have and will make contributions to the field that amplify our knowledge and transform our critical understanding of our craft. Since I am privileged with the mic during this auspicious time, I will take this opportunity to address a fundamental question that was raised at one of yesterday’s roundtables: where and when do we locate the “Middle Ages” in a global context? In other words, how can we reevaluate our Eurocentric biases and take into account cultures around the world that don’t fit traditional definitions of medievalism?

The organizers of the Kalamazoo roundtable, the University of Virginia’s DeVan Ard and Justin Greenlee, created a forum to discuss the fraught term “medieval” from various perspectives, including Buddhist art in China (Dorothy Wong), the pre-Islamic Jahiliyyah period (Aman Nadhiri) and the challenges of accurately representing the Middle Ages in the classroom (Christina Normore). The speakers and moderator Zach Stone strove to challenge the artificial boundaries that are often used to constrict the idea of the medieval and to consider, in the words of Nadhiri, “the Middle Ages as a period without the parameters of time.” I offer here an adapted version of my own presentation, which considers the limits of the term “medieval” through the history of the printing press in the Muslim world.

Of all the metrics that various disciplines use to demarcate the end of the Middle Ages—shifts in military tactics, game-changing historical figures, scientific discoveries, etc.—the arrival of Johannes Gutenberg’s printing press in Germany is often seen as the critical moment when Western culture was ‘reborn’ into a new era. Medievalists know well that the effects of this new technology were not as immediate or as clear cut as many outside the field sometimes think, but the ability to disseminate materials more efficiently and more widely led to changes in the economy, literacy, and writing practices rivaled only by the recent progress of the digital age.

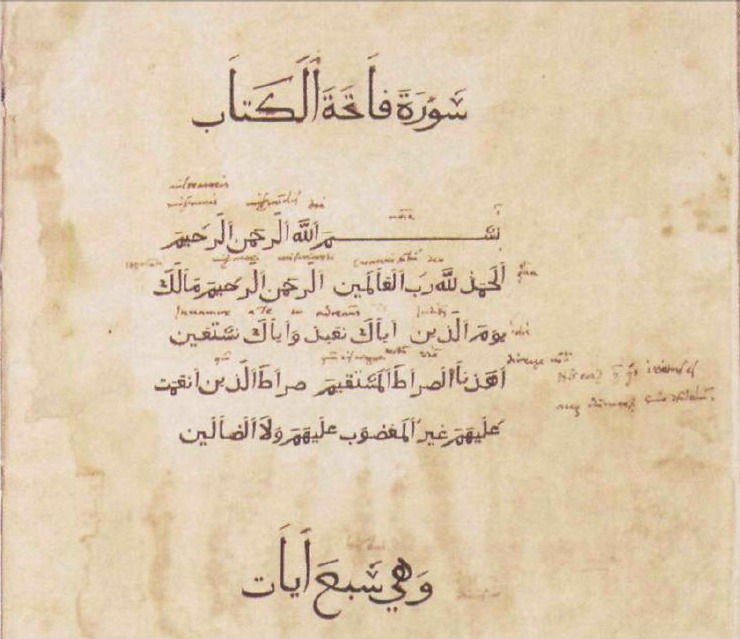

The history of movable type in Arabic provides a point of departure for wider discussions of how to bookend a historical era in the Middle East and North Africa as well as other predominantly Muslim populations. Although the printing press made its way to the Ottoman Empire not long after its introduction in Europe, it was almost immediately forbidden to print in Arabic. Among the various political, social, and theological reasons for this legislation, I argue that the sanctity of the Arabic language itself created resistance to movable type. According to Islam, Arabic is the direct language of God communicated through the angel Gabriel. Many believe that translations of the Qur’an are no longer the holy book, and throughout the early centuries of Islam there were meticulously-enforced rules for the style of writing that could be used for certain texts.

The clumsy attempts of early printers to negotiate the connectors, diacritics, and shape-changing letters of Arabic writing could not hope to represent the word with the accuracy and beauty that it required. Continuing attempts to this day to create functional Arabic fonts and Turkey’s twentieth-century switch from Arabic to Roman script demonstrate that these challenges are still being negotiated. This narrative of technical and literary development, so vastly different from that of Western Europe, offers a lens through which we can consider other intellectual and cultural differences that complicate comparisons between Western Europe and the Arab world.

Erica Machulak

PhD in English

University of Notre Dame

Founder of Hikma Strategies