My semester at Notre Dame as the Astrik L. Gabriel Postdoctoral Fellow was fortuitous in several ways. As I began to revise my dissertation into a book, I benefited greatly from the resources of the Medieval Institute, the kind guidance of Notre Dame’s faculty, and the friendship of several graduate students and postdoctoral fellows. During my short tenure, Irish football also went undefeated in the regular season! (Take note deans and future hiring committees.) Last but not least, I discovered a remarkable manuscript at Saint Mary’s College: Cushwa-Leighton Library, Ms. 1.

As David Gura notes in his catalog entry, Ms. 1 was probably copied in Germany in the late-twelfth or early-thirteenth century.[1] It contains portions of Peter Lombard’s Sentences and Burchard’s Decretum, as well as minor excerpts from Rather of Verona’s Synodica and Adelgar’s De studio virtutum. When I first came across Ms. 1, I was immediately interested because I had examined many similar copies of Burchard’s Decretum in my dissertation.[2] I was even more excited to discover that Ms. 1 is unknown to historians of canon law![3]

Although there is much work yet to be done, I would like to share some of my initial findings regarding Ms. 1.

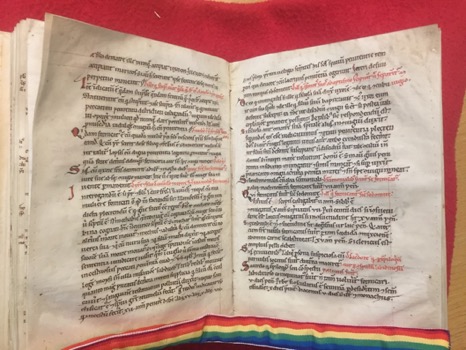

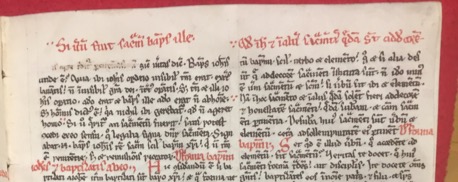

In its current form, Ms. 1 consists of two distinct sections. The first section contains the Sentences (ff. 1ra-18vb) while the second section contains Decretum and the other minor texts (ff. 19r-38v). The small hand and two columns of the former section is clearly distinguishable from the larger hand and single column of the latter section. At some point these two sections, originally distinct, must have been bound together.

Burchard’s Decretum and Saint Mary’s Ms. 1

The Decretum was compiled by Burchard, bishop of Worms, between 1012 and 1023, and numbers among the most important canon law collections of the Middle Ages. Divided into twenty books, the Decretum focuses on matters of diocesan administration, including the rights and duties of the bishop, the regulation of clerical (mis)conduct, and the punishment of lay crimes and sins through penance. About 78 complete copies of the Decretum survive today.

As noted by Gura, the Decretum excerpts in Saint Mary’s Ms. 1 mostly come from Book 19. Book 19, which is also known as the Corrector, explains how to judge, assign, and enforce penances.

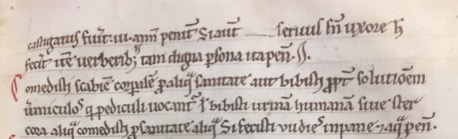

In recent years, the Corrector has received a great deal of attention from cultural historians due to its strange prescriptions against magic, witchcraft, and sexual deviancy. For example, the Corrector includes one of the earliest known references to werewolves! Consider also this fascinating example:

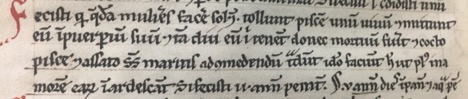

“Have you done what certain women are accustomed to do? They take a living fish, place it between their legs, and hold it there for a while until it has died. Then, having boiled and roasted the fish, they give it to their husbands to eat. They do this so that [their husbands] might become more inflamed in love for them. If you have done this, you should do penance for two years.”

“Fecisti quod quaedam mulieres facere solent? Tollunt piscem unum vivum, et conmittunt eum in puerperium suum, et tamdiu eum ibi tenent, donec mortuus fuerit, et, cocto pisce vel assato, suis maritis ad comedendum tradunt, ideo faciunt hoc, ut plus in amorem earum inardescant? Si fecisti, duos annos poeniteas.”

The Corrector has traditionally been considered a penitential. The penitentials first emerged in Ireland and England in the fifth and sixth centuries and were brought to the Continent by missionary-monks such as Columbanus and Boniface in the seventh and eighth centuries. According to most scholars, the penitentials describe a process of private, voluntary confession distinct from the mandatory public penances of the canon law collections. As such, scholars often claim that the Corrector was used separately from the rest of the Decretum.

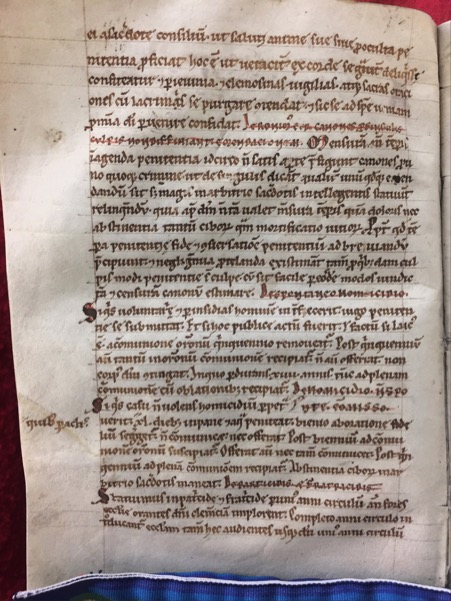

According to my analysis, however, Ms. 1 also contains major excerpts from other parts of the Decretum, including books 2, 6, 9, 12, and 17. These books covers topics such as clerical misconduct (Book 2), homicide (Book 6), marriage law (Book 9), perjury (Book 12), and sexual offenses (Book 17). While most of these texts appear after the Corrector material, there is also some overlap. As can be seen below, several canons from Book 6 on homicide, for example, appear on f. 22v near the beginning of the Corrector section.

As I argued in my dissertation, abbreviations such as Saint Mary’s Ms. 1 reveal that medieval readers and users of the Decretum did not see the Corrector as a manual of private confession separable from the Decretum. Rather, they saw it as a practical summary of the Decretum and did not hesitate to combine it with texts taken from other parts of the collection.

An Augsburg Connection?

Based on my work with similar manuscripts from southern Germany, I have found several indications that Ms. 1 (at least the latter section) has some connection to the diocese of Augsburg:

1. On ff. 20r-22r appear excerpts from the De studio virtutum/Admonitio ad Nonsuindam reclusam, which is printed in Migne’s Patrologia Latina vol. 132. Migne attributed the text to a certain Adalger who was supposedly a bishop of Augsburg in the tenth century.

2. On f. 19rv appear excerpts from Rather of Verona’s Synodica. Only four manuscripts of this text survive and one of them belonged to Diessen Abbey in the diocese of Augsburg. This manuscript is now Munich, Bayerische Staatsbibliothek, CLM 5515 (s. xii).

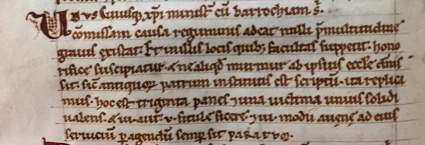

3. On f. 19v appears a text on the duties of archdeacons which begins “Unuscuiusque christi minister…”. I have located this text only in two Augsburg manuscripts: Munich, Bayerische Staatsbibliothek, CLM 3851 (s. ixex) and 3853 (s. x3/4).

4. In my dissertation, I argued that Munich, Bayerische Staatsbibliothek, CLM 4570 (completed in 1108) was the Augsburg copy of Burchard’s Decretum. If I am correct, Ms. 1 was probably copied from CLM 4570.

For more information on Ms. 1, please refer to my article which will appear in the December 2019 volume of the Journal of Medieval History. Or you can go see it in person at Saint Mary’s College!

John Burden, PhD

Yale University

[1] David T. Gura, A Descriptive Catalogue of the Medieval and Renaissance Manuscripts of the University of Notre Dame and St. Mary’s College (Notre Dame, IN: University of Notre Dame Press, 2016), 558-61.

[2] John Burden, “Between Crime and Sin: Penitential Justice in Medieval Germany, 900-1200” (Ph.D. Dissertation: Yale University, 2008).

[3] Lotte Kéry, Canonical Collections of the Early Middle Ages (ca. 400-1140) (Washington, D.C.: Catholic University of America Press, 1999).