As a specialist in the study of women’s education and literacy in England in the Middle Ages, I’m asked this question a lot. I’ll cut to the chase: YES.

How do we know this?

Medieval England (on which I’ll focus this blog) was a multilingual nation.1 English had been its primary vernacular from the time of the Anglo-Saxons (about 450) until the Norman Conquest of 1066, when French became the language of the nobility, government, and diplomacy.2 By the mid-fifteenth century, though, English had reasserted dominance as the primary vernacular language, while the Church, clerics, and higher education continued to use Latin.3 Because medieval English people would have heard and used all three languages in daily life, children were taught to read and speak all of them.4 Whether children’s reading knowledge became advanced depended on the importance of reading in their lives and what socioeconomic station they attained. In fact, most of the evidence for literacy survives from the upper classes; uncovering the history of less privileged groups remains difficult.

In infantia

Medieval scholars commonly thought of childhood in three divisions: infantia (birth to about 7 years), pueritia (about 7 to 14 years), and adolescentia (about 14 to 21 years).5 The teaching of reading began in infantia with parents and nurses, if the family could afford such help.

Girls and boys began by learning the letters of the Latin alphabet and the sounds they made. In this way they acquired the basic skills of early reading, called contemporaneously sillibicare (sounding out syllables) and legere (sounding out words), even if they didn’t understand what those sounds or words meant.6 Singing might have been used as well to teach pronunciation, as sung Latin was used in church services. Because reading was important to promote spiritual instruction, and had indeed been cited at least as far back as Jerome in the fourth century as a reason girls should be taught to read, some of the earliest texts learned were the Pater Noster, the Ave, and the Creed. Alphabets and these simple prayers could be written out on a variety of surfaces: boards, painted walls, wooden trays covered in ash or sand, ceramic or metal vessels, or hand-held tablets made of materials such as slate, horn, or board covered in parchment (more on this below).

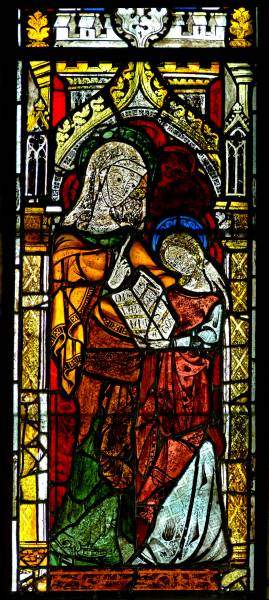

Beginning around 1300 in England, medieval parents had a model of teaching in St. Anne, the mother of the Virgin Mary. Depictions of her teaching Mary to read appeared in stained-glass windows, manuscript illuminations, wall paintings, and other artistic representations.7 One such survives today in the Church of St. Nicholas in Stanford-on-Avon, Northamptonshire, England.

In this window, Mary is shown sitting in Anne’s lap and holding a bound book with letters written on its pages. She holds the book open so the text is visible to the reader. Her mother Anne points upward, in a gesture both teacherly and pointing heavenward, perhaps emphasizing the importance of reading for spiritual development.8

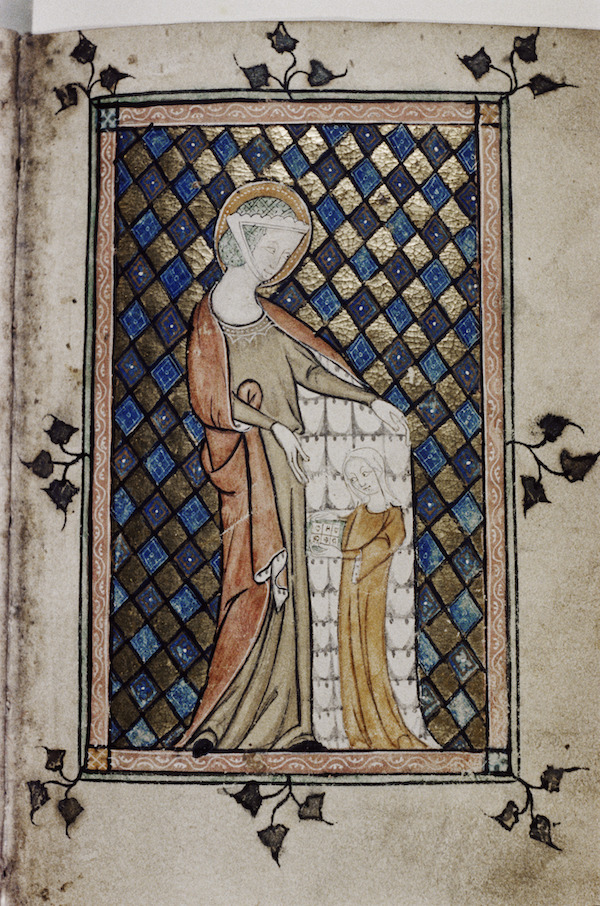

This beautifully-painted miniature from a Book of Hours shows Anne and a young Mary holding a book together. With her right hand, Anne isolates text for Mary to examine.

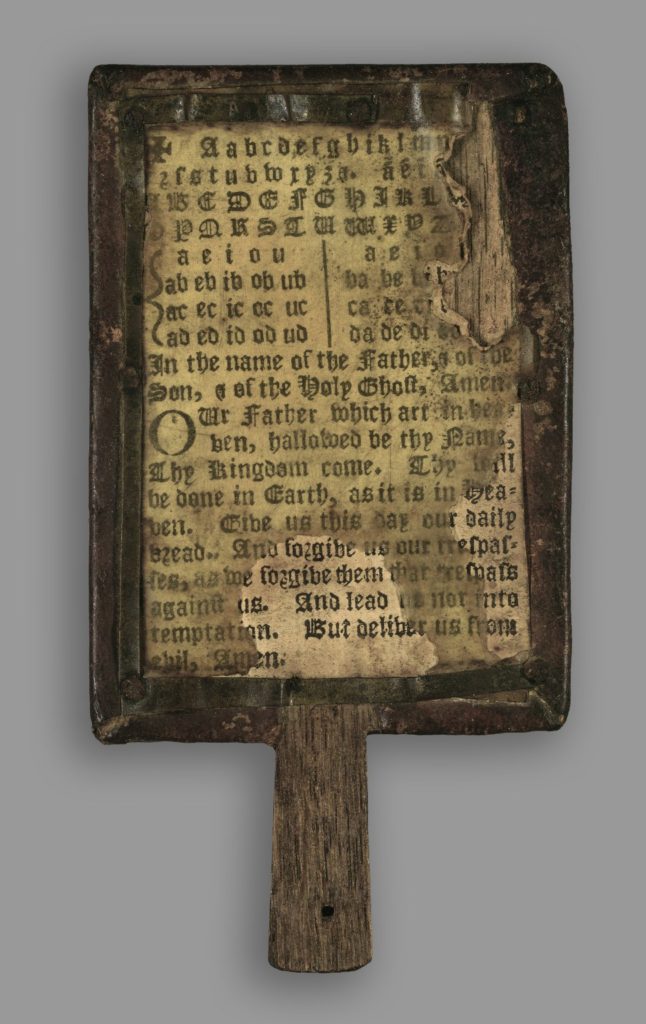

Other surviving representations show Anne using a hornbook (mentioned above) to teach Mary to read. This illustration comes from a Book of Hours that originated in England around 1325–1300.

This detail shows the hornbook more closely.

Though the hornbook was at least a medieval invention (discussed recently by Erik Kwakkel and Trinity College, Cambridge, librarians), it survives only from early modern centuries, as in this example, created in London around 1625. The text is printed on sheepskin parchment and fixed to an oak paddle with a brass frame and iron nails; the handle is used for holding the hornbook. The parchment is laminated over with a processed animal horn (hence the name) to protect the text.

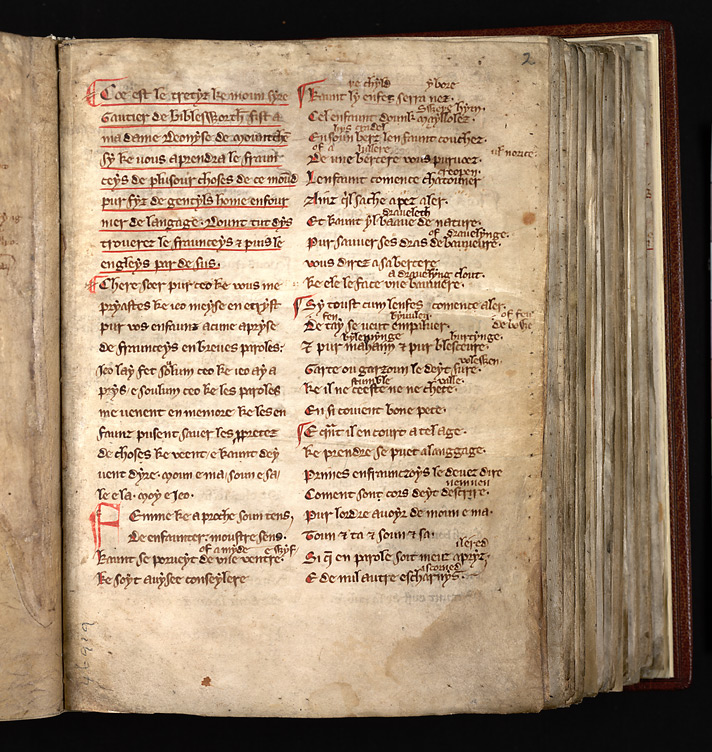

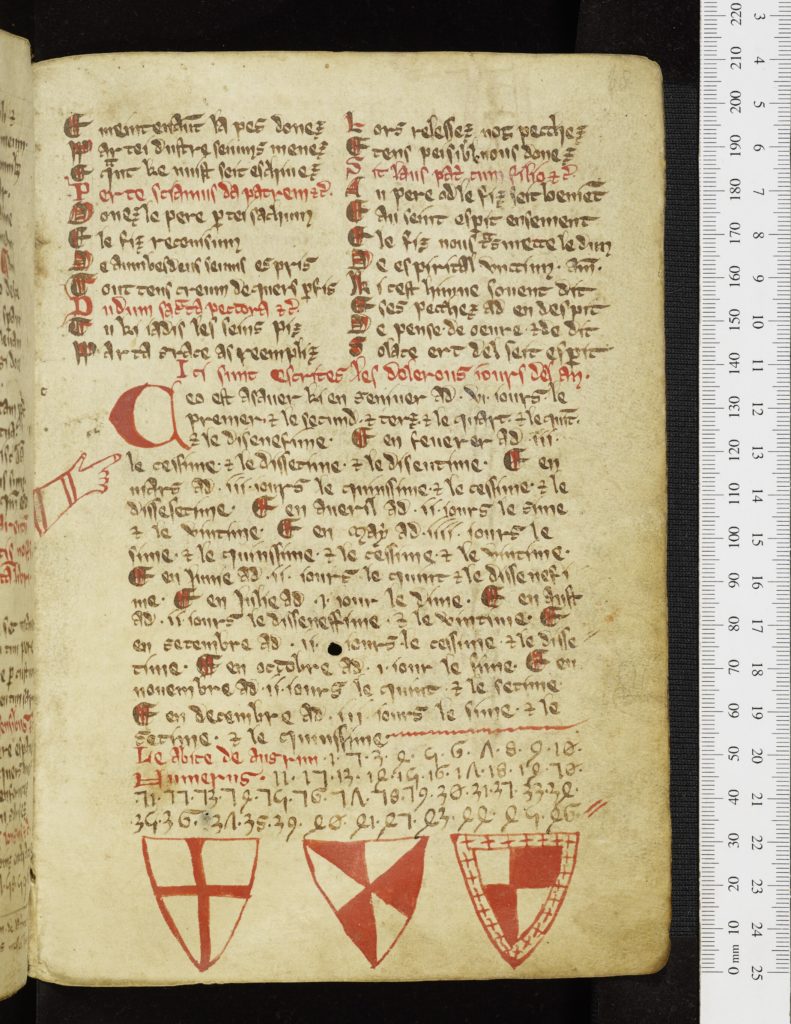

A text from the 1230s, written by a layman, Walter of Bibbesworth, also reveals much about how boys and girls learned, especially languages, in a gentry household. Bibbesworth was a wealthy English landowner and a knight who wrote this book for his neighbor and fellow member of the gentry, Dionisie de Munchensi. Dionisie had three young children to educate, and as part of the expectations of their class, they would have needed to learn a French more advanced than what they would have picked up through everyday living. The image below shows the opening leaf of Walter of Bibbesworth’s Tretiz.

Walter addresses Dionisie in column 1, lines 10-20, identifying the purpose of his text: “Chere soer, pur ceo ke vous me / pryastes ke jeo meyse en ecsryst [sic] / pur vos enfaunz acune apryse / de fraunceys en breve paroles” (Dear sister, because you have asked that I put in writing something for your children to learn French in brief phrases). What follows is a narrative poem, beginning in column 1, line 21, that describes childhood, starting with birth and ending in young adulthood with a large household feast. In each scene, Walter presents French vocabulary for Dionisie’s children to learn.

Many clues in the text demonstrate that the physical book was shown to children so they could learn the reading of words on a page, not just the sounds of them. Walter gives many homophones, for example, that would only make sense in writing, rather than in pronunciation. Some of the vocabulary also has English translations written in between the lines of the main text. You can see this in the image above in the poem, which starts at column 1, line 21, and goes into column two. All the smaller words written between the lines give the English translation of the main text, which is written in French.

In pueritia and adolescentia

Once they moved into pueritia (about 7-14 years of age), girls of the upper classes would often transition into the care of a mistress (called at that time magistra, magistrix, or maitresse). The mistress provided education in such things as deportment, embroidery, dancing, music, and reading.9 For any skills the mistress did not herself have, she could bring in other household members, such as the minstrel for musical training, the chaplain for more advanced reading and spiritual instruction, and the huntsman for hunting. Specialized academic tutors could teach girls more advanced academic subjects. Sometimes these well-to-do girls were sent to other households to be fostered, serving as ladies-in-waiting to upper-class women. Girls, especially those of the upper classes, could be sent to nunneries as well (sometimes beginning in infantia) for education. Not all girls sent to nunneries were meant for the vocation of nun.10

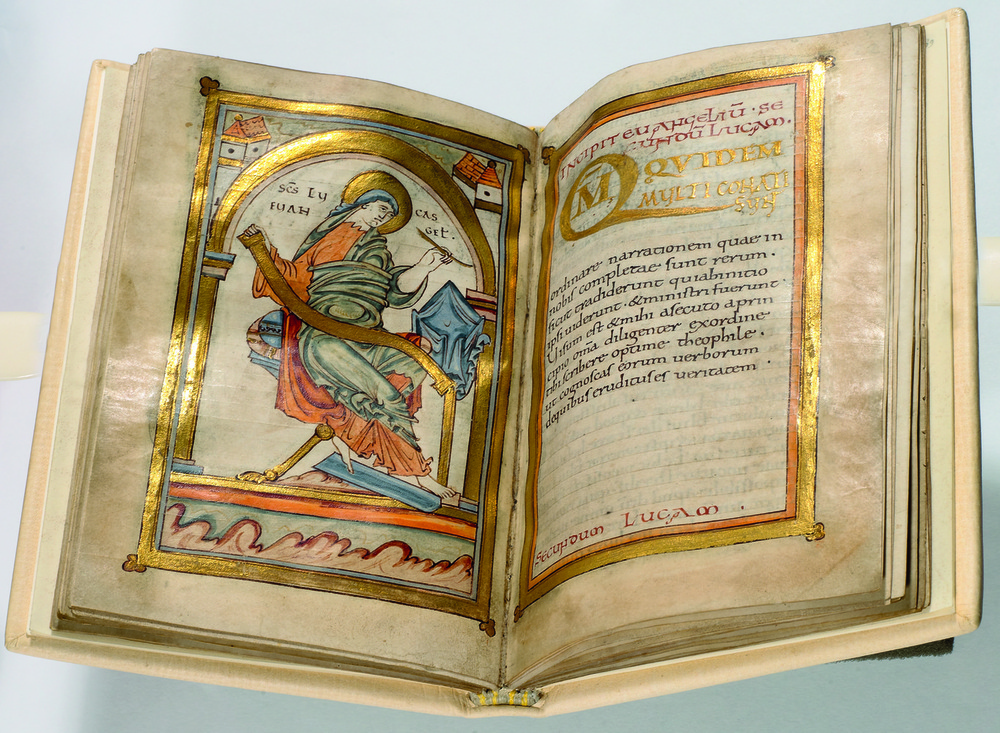

As their reading abilities progressed, girls and boys moved on to reading comprehension (intelligere) and began to read more sophisticated spiritual texts, such as prayer-books, books of hours, psalters, antiphonals, and saints’ lives. They also would continue on, as personal libraries grew in the thirteenth century, in reading romances, histories, poetry, classical authors, theology, philosophy, and more. It is most likely, given that women were not admitted to the university (unlike boys, who could progress from this stage to Latin grammar school and then on at a university level to the study of business, liberal arts, medicine, canon or civil law, or theology), that the reading of these last few would have been limited to girls whose families could afford private tutors.

In adulthood

By the time they reached adulthood, women who were privileged enough to have obtained a sophisticated education and their own libraries could be avid readers.

The historical and literary records provide examples of such sophisticated learning, primarily among the nobility. For example, the Norman monk and chronicler Robert of Torigni (c.1110–1186), praised the education of St. Margaret of Scotland (d. 1093) and her daughter Matilda (1080–1118), wife of Henry I, writing, “Quantae autem sanctitatis et scientiae tam saecularis quam spiritualis utraque regina, Margareta scilicet et Mathildis, fuerint” (Of how great holiness and learning, as well secular as spiritual, were these two queens, Margaret and Matilda).11

In a different Latin life, commissioned by Matilda about her mother Margaret, the biographer describes how Margaret from her childhood would “in Divinarum lectionum studio sese occupare, et in his animum delectabiliter exercere” (occupy herself with the study of the Holy Scriptures, and delightfully exercise her mind) and notes that her husband, King Malcom III, cherished the “libros, in quibus ipsa vel orare consueverat, vel legere” (books, which she herself used either for prayer or reading), even though Malcom himself could not read Latin.12

This image above shows the unidentified female patron of this Book of Hours kneeling on a prie-dieu, her prayer book open to the text “Maria mater gratiae” (Mary, mother of grace). This open book with its discernable text has several functions: it leads the reader into the prayer; it demonstrates the piety of the patron, kneeling in prayer before both her spiritual book and the Blessed Virgin and Christ (illustrated on the facing leaf); and it shows one of the primary purposes of teaching children to read: being able to use spiritual texts in personal devotion.

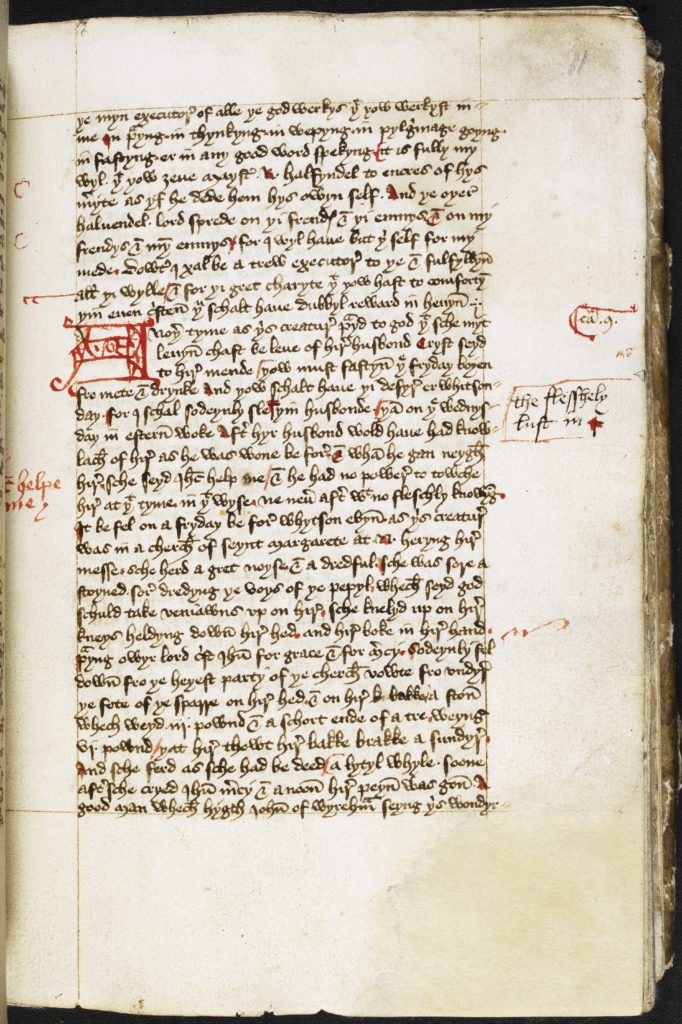

Even women who were not noble and who were not able to read much Latin possessed and used books such as the one pictured above. In the mid-fifteenth century Englishwoman Margery Kempe wrote through her scribe of a memorable time in her church of St. Margaret in King’s Lynn when a chunk of masonry fell from the ceiling down onto her as she was praying with her prayer book in hand.

The image below comes from her Book of Margery Kempe as preserved in London, British Library, Additional MS 61823. Lines 24-28 narrate, “Sche knelyd upon hir / kneys heldyng down hir hed. and hir boke in hir hand. / prayng owyr lord crist ihesu for grace and for mercy. Sodeynly fel / down fro þe heyest party of þe cherche vowte fro undyr / þe fote of þe sparre on hir hed and on hir bakke a ston / whech weyd .iii. pownd” (She knelt on her knees, bowing down her head and holding her book in her hand, praying to our Lord Christ Jesus for grace and mercy. Suddenly fell down from the highest party of the church out from under the foot of the rafter onto her head and her book a stone which weighed three pounds). She survived, for which she credited the mercy of Christ.

Finally, a note on those of the working classes. I have not discussed them in detail as it is unfortunately difficult, in fact nearly impossible, to say much about the reading skills of those who left few or no records behind: the great majority of women (and men) of the medieval population were laborers who left little trace in the written record. Yet as we see from the image here below, even for working women, especially in the last few centuries of the Middle Ages, possession and use of books was within the norm, provided those books could be afforded.

Conclusion

My focus here has been tightly on the teaching of reading to medieval English girls. Girls and boys alike were taught to read, and began their reading education in the same ways. Boys alone could attend the medieval university and reach the highest (and best educated) ranks of clerics, but if girls had access to the right resources, they too could be highly educated. The evidence demonstrates that the teaching of reading was not linked specifically to gender; rather, it was a function of both socioeconomic station and the usefulness of such skills for one’s life.

If you’re interested in this topic, I cover the subject in much greater detail, with many other examples and suggested readings, in my article, “Women’s Education and Literacy in England, 1066–1540,” in the “Medieval and Early Modern Education” special issue of History of Education Quarterly, and the accompanying HEQ&A podcast.

Megan J. Hall, Ph.D.

University of Notre Dame

Twitter @meganjhallphd

[1] On languages in medieval England, see Amanda Hopkins, Judith Anne Jefferson, and Ad Putter, Multilingualism in Medieval Britain (c. 1066–1520): Sources and Analysis (Turnhout, Belgium: Brepols, 2012).

[2] W. M. Ormrod, “The Use of English: Language, Law, and Political Culture in Fourteenth-Century England,” Speculum 78, no. 3 (July 2003), 750–87, at 755; and William Rothwell, “Language and Government in Medieval England,” Zeitschrift für französische Sprache und Literatur 93, no. 3 (1983), 258–70.

[3] David Bell, What Nuns Read: Books and Libraries in Medieval English Nunneries (Kalamazoo, MI: Cistercian Publications, 1995), 57.

[4] On the complexities of a trilingual England, with a number of helpful citations therein for further reading, see Christopher Cannon, “Vernacular Latin,” Speculum 90, no. 3 (July 2015), 641–53.

[5] A variety of frameworks were imposed upon the ages of humankind, though these major divisions for the stages of childhood were fairly commonly accepted. For a discussion, see Nicholas Orme, From Childhood to Chivalry: the Education of the English Kings and Aristocracy, 1066-1530 (London: Methuen, 1984), 5–7; and Daniel T. Kline, “Female Childhoods,” in The Cambridge Companion to Medieval Women’s Writing, ed. Carolyn Dinshaw and David Wallace (Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press, 2003), 13–20, at 13.

[6] Jocelyn Wogan-Browne, “‘Invisible Archives?’ Later Medieval French in England,” Speculum 90, no. 3 (July 2015), 653–73. For more on levels of reading Latin, see Bell, What Nuns Read, 59–60; and Malcolm B. Parkes, “The Literacy of the Laity,” in Scribes, Scripts, and Readers: Studies in the Communication, Presentation, and Dissemination of Medieval Texts, 1976 (London: Hambledon Press, 1991), 275–97, at 275.

[7] On the cult of St. Anne and the teaching of reading, see Nicholas Orme, Medieval Children (New Haven, CT: Yale University Press, 2001), 244–45; and Clanchy, “Did Mothers Teach their Children to Read?,” in Motherhood, Religion, and Society in Medieval Europe, 400–1400: Essays Presented to Henrietta Leyser, ed. Conrad Leyser and Lesley Smith (Farnham, UK: Ashgate, 2011), 129–53. For further examples and a detailed analysis of the Education of the Virgin motif, see Wendy Scase, “St. Anne and the Education of the Virgin,” in England in the Fourteenth Century: Proceedings of the 1991 Harlaxton Symposium, ed. Nicholas Rogers (Stamford, UK: Paul Watkins, 1993), 81–98.

[8] For a discussion of this window, see Orme, Medieval Children, 244–45.

[9] Boys (especially royal princes) typically followed the same path of moving from the nursery into the care of an educator-caretaker: pedagogus (a term used into the eleventh century) or magister or me[i]stre (terms in use from the twelfth century forward) (Orme, From Childhood to Chivalry, 19).

[10] Excellent reading on the education of girls in nunneries is found in Eileen Power, Medieval English Nunneries, c. 1275 to 1535 (Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press, 1922); Alexandra Barratt, “Small Latin? The Post-Conquest Learning of English Religious Women,” in Anglo-Latin and Its Heritage, Essays in Honour of A. G. Rigg on His 64th Birthday, ed. Siân Echard and Gernot R. Wieland (Turnhout, Belgium: Brepols, 2001), 51–65; and J. G. Clark, “Monastic Education in Late Medieval England,” in The Church and Learning in Late Medieval Society: Essays in Honour of R. B. Dobson; Proceedings of the 1999 Harlaxton Symposium, ed. Caroline Barron and Jenny Stratford (Donington, UK: Shaun Tyas/Paul Watkins, 2002), 25–40; and Dorothy Gardiner, English Girlhood at School: A Study of Women’s Education Through Twelve Centuries (Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press, 1929).

[11] Robert of Torigni [Robertus de Monte], Historia nortmannorum liber octavus de Henrico I rege anglorum et duce northmannorum, ed. J.-P. Migne, Patrologia cursus completus, series latina 149 (Paris, 1853), col. 886; translated in “History of King Henry the First, by Robert de Monte,” ed. Joseph Stevenson, The Church Historians of England vol. 2, part 1 (London, 1858), 10.

[12] Transcribed in Symeonis Dunelmensis Opera et Collectanea, ed. J. Hodgson Hinde, vol. 1 (London, 1868), at 238, 241, from the version preserved in London, British Library, Cotton MS Tiberius D iii, fols. 179v–186r (late twelfth century).