When we imagine imprisoned spaces, we often think of solitude, despair, and hopelessness. For medieval prisoners in the Tower of London or in London’s Newgate prison, this was often the case, particularly for debtors and the poorest inmates.

However, Chaucer, whose apartment at Aldgate was about a 10 minute walk from the Tower, often portrays prison as much more communal and permeable than we might imagine.

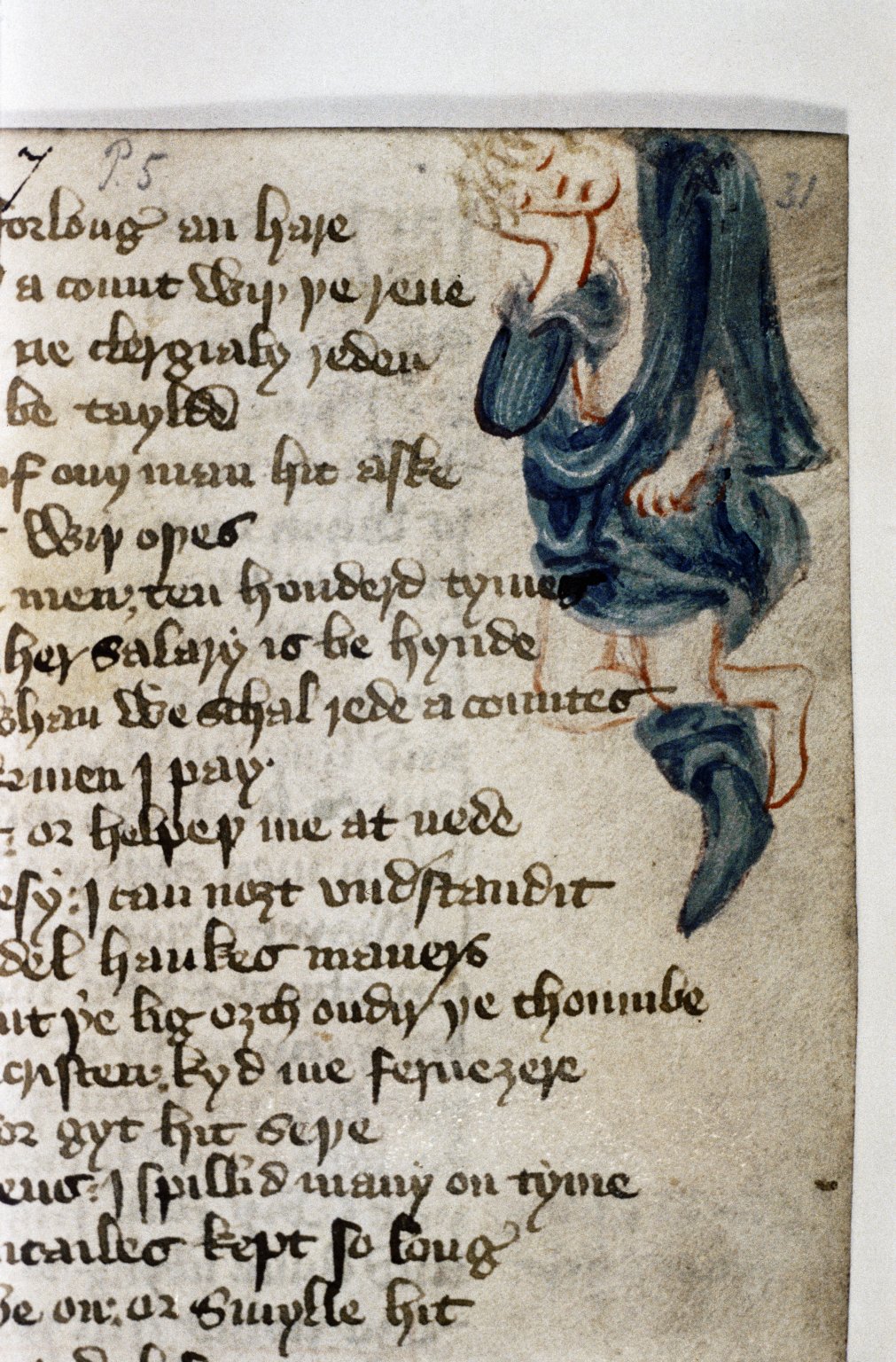

Take Palamon and Arcite of The Knight’s Tale for example. The knights share an imprisoned space, and though both are sentenced “to dwellen in prisoun / Perpetuelly,” they manage to leave their tower (I. 1023-4). Moreover, while imprisoned, the two characters have a close connection with the outside world. Emily’s garden shares a wall with their prison tower, and the two knights can gaze out at the seeming freedom of the beautiful maiden:

And so bifel, by aventure or cas,

That thurgh a wyndow, thikke of many a barre

Of iren greet and square as any sparre,

He cast his eye upon Emelya (l. I. 1074-7).[1]

Even through this small, barred window, love’s arrow pierces the imprisoned knights. Though that arrow further ensnares the knights in a metaphorical prison of love-longing, the action also demonstrates that their physical prison space is not impenetrable.

Julia Boffey details several other depictions of imprisonment in Chaucer’s corpus.[2] If we look closely at each of her examples, we again see the potential for permeability and/or community in an imprisoned space.

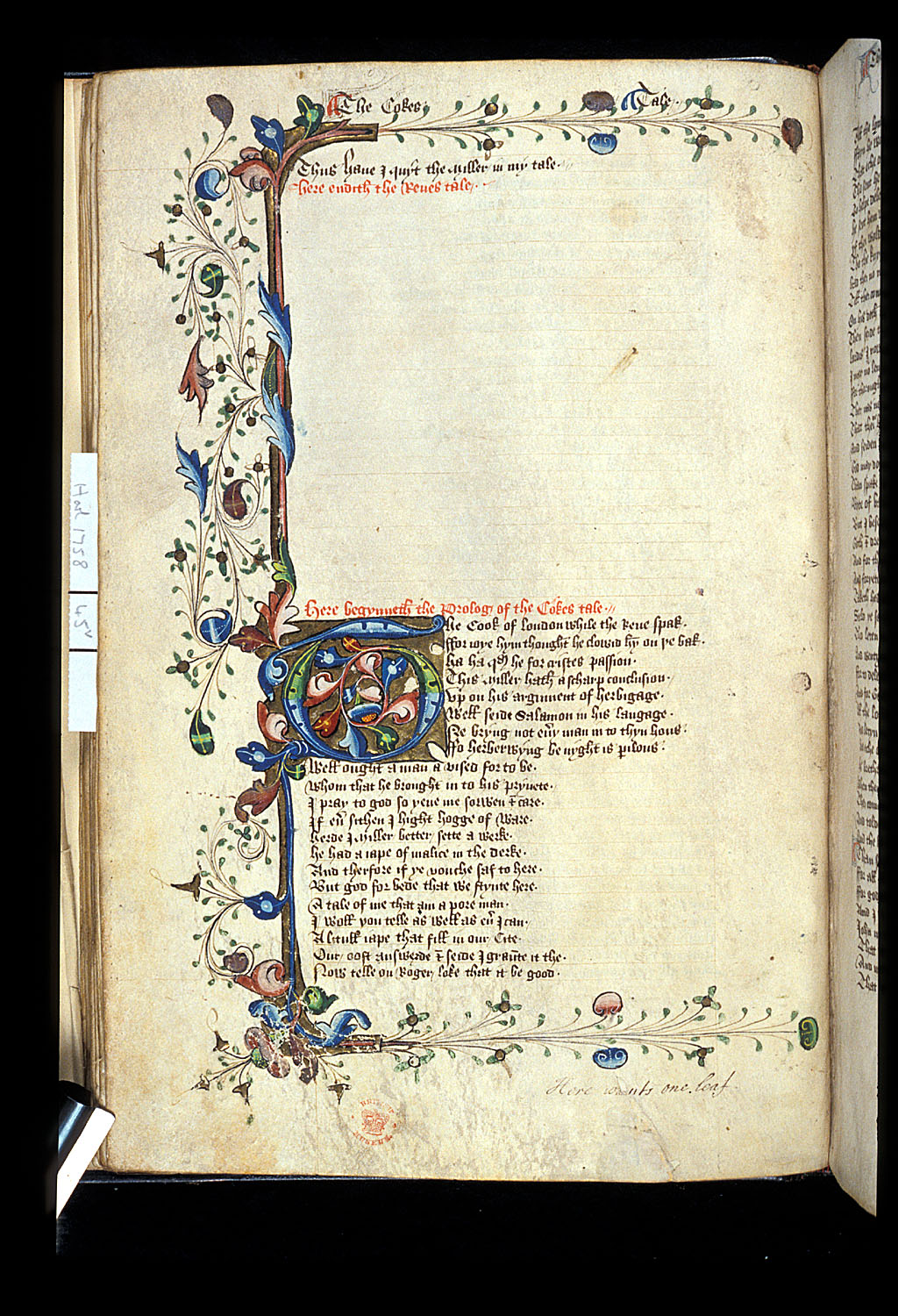

There is Perkyn, the protagonist of the Cook’s Tale, who is “somtyme lad with revel to Newegate” (l. I. 4402). Newgate prison was notorious for its vile conditions.[3] However, visitors were allowed inside the prison gates, and that Perkyn was “somtyme” in the prison could indicate that he was in and out of the space frequently.

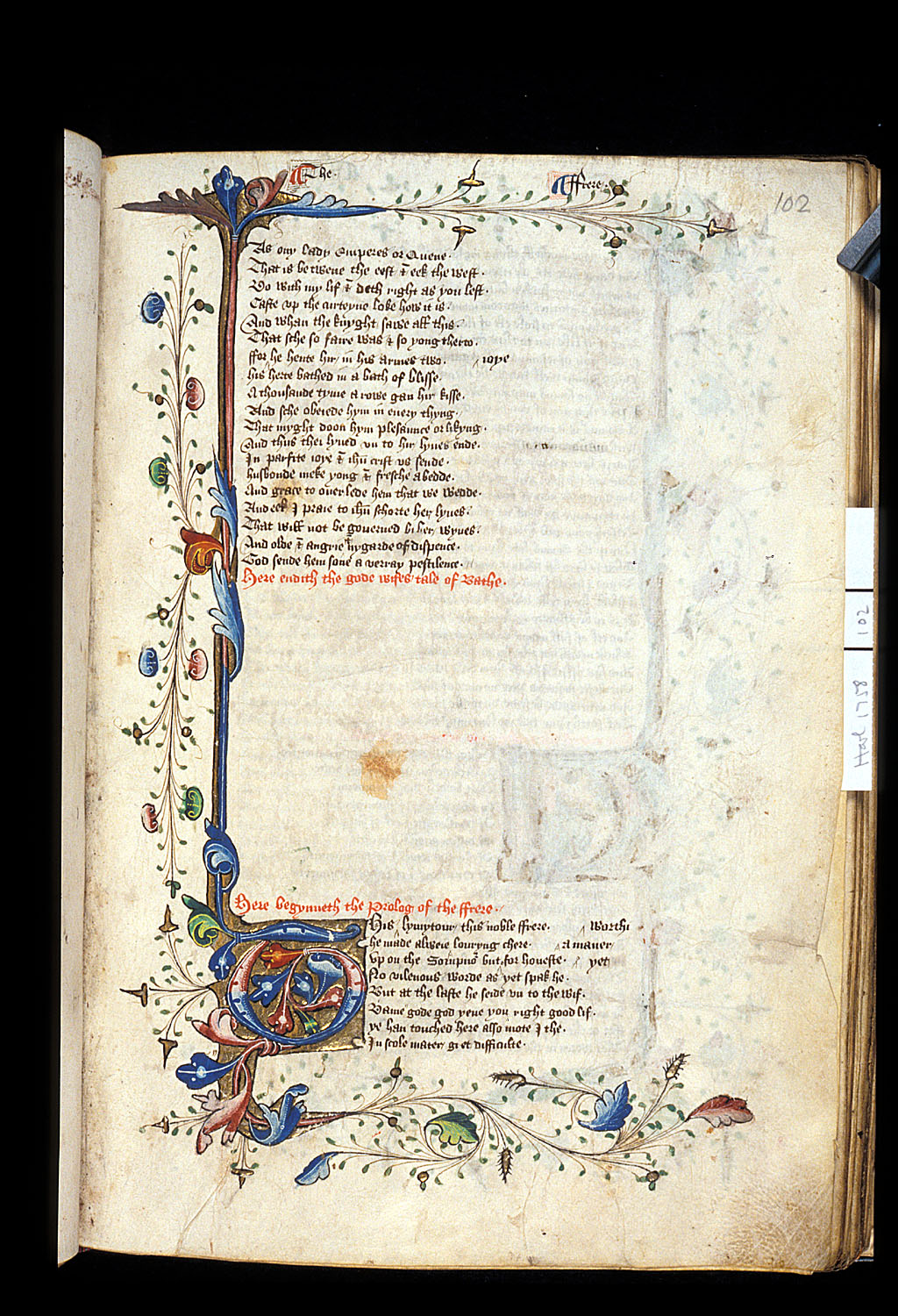

Theseus’s prison in Chaucer’s Legend of Good Women is so accessible that Ariadne and her sister can hear him “compleynynge” from their chambers (l. 1971). And though Philomela, in the next LGW narrative, initially seems conquered, she is still able to give a woven cloth to a serving boy and communicate with her sister (ll. 2335-70).

In actual prison situations, those prisoners who had the funds to live comfortably were able to study, read, write and communicate with their fellow inmates.[4] [Tune in next week to see my post about an imprisoned reader of Chaucer!] And those who wrote poetry from prison often used the prison as much more than an image of enclosure.

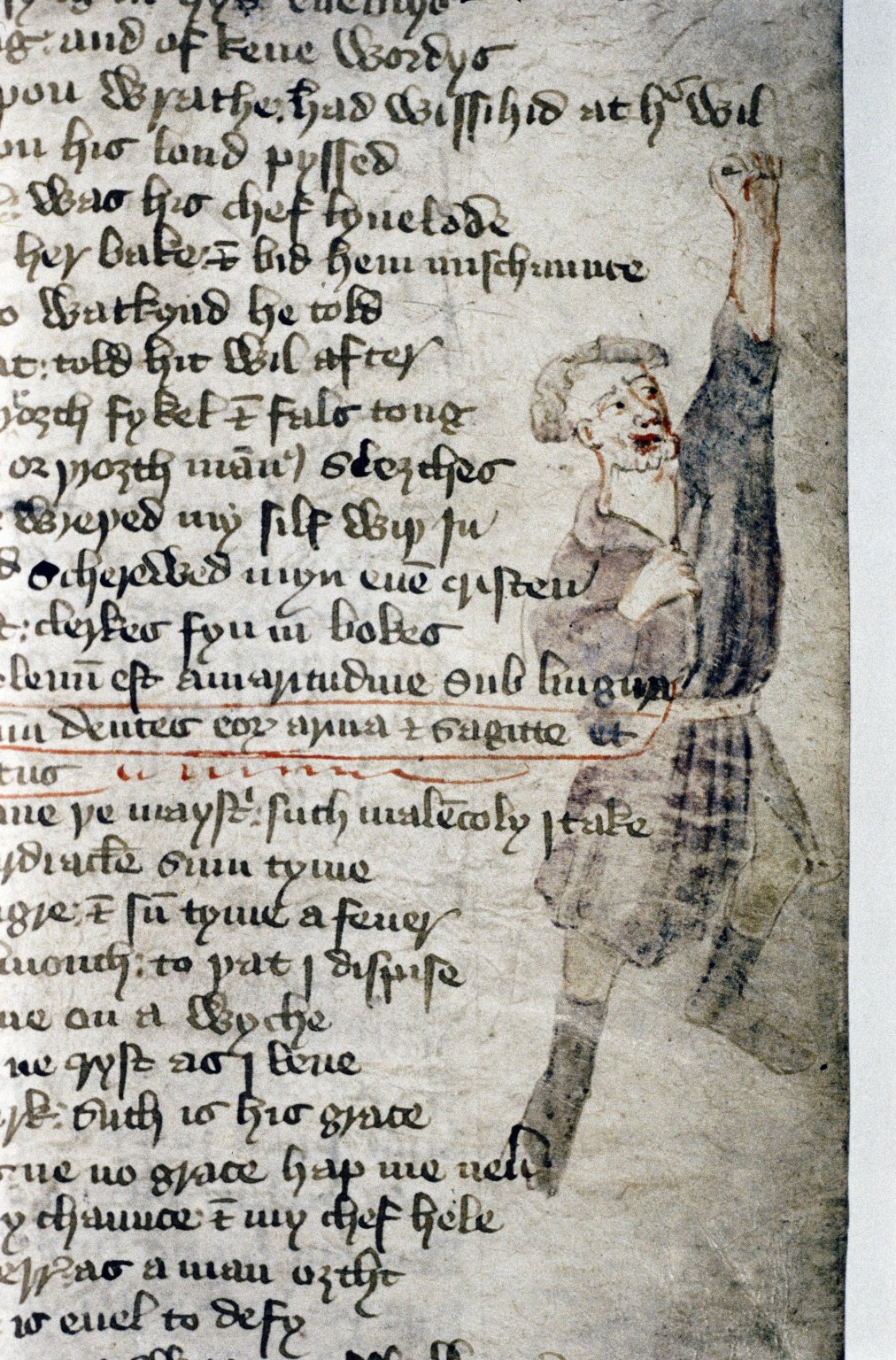

Prison could be a space of community and a space for creativity. Boethius, whom Chaucer translated, ultimately found answers to important philosophical questions through his prison experience. Moreover prison poets, like Charles d’Orleans and King James I of Scotland, wrote during their imprisonments to confront questions of fortune, providence, and even love.[5]

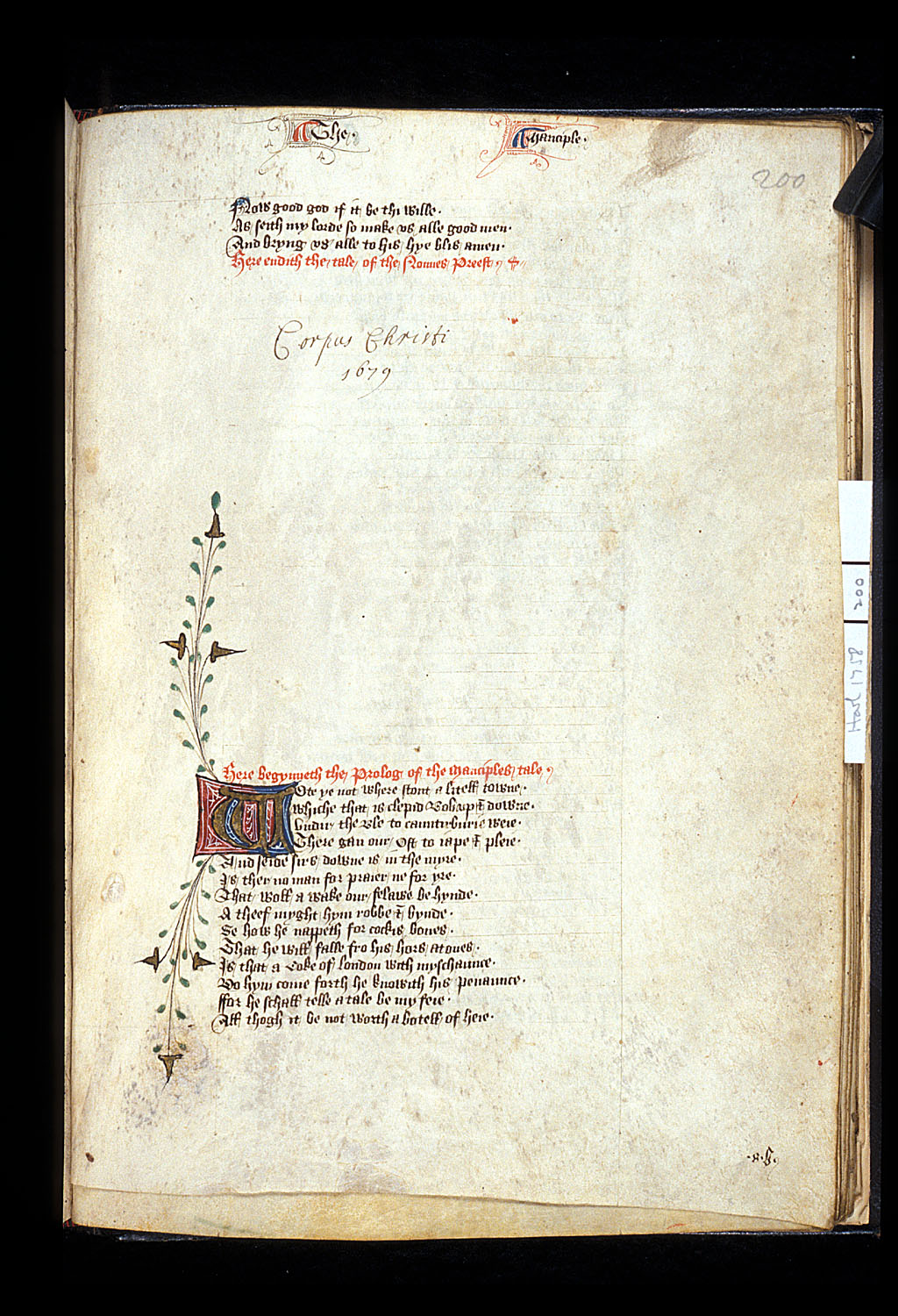

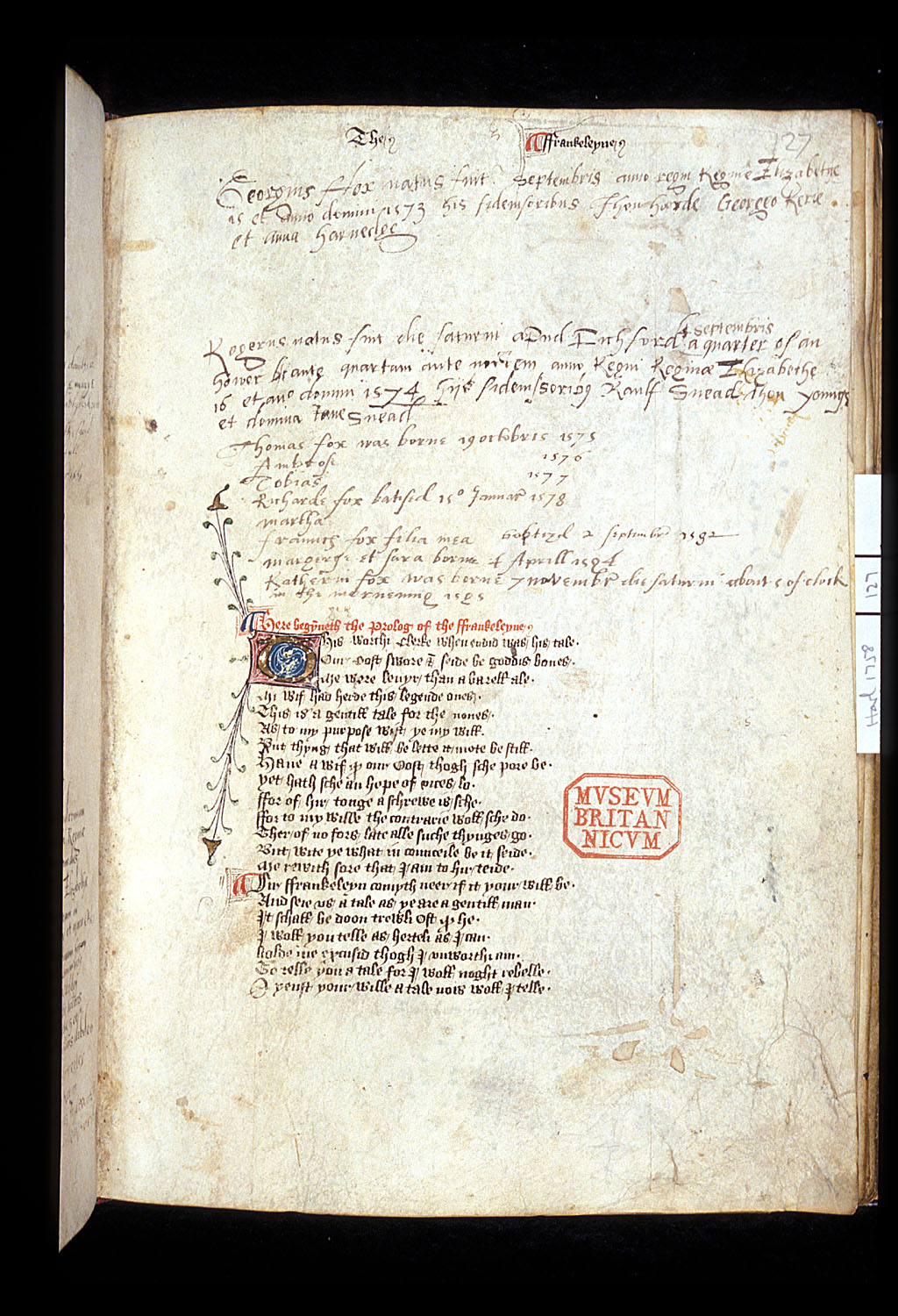

Notably, prison poets following Chaucer were often influenced by him and by Boethius mediated through him.[6] Chaucer, who was held captive briefly in 1360, had communicated something meaningful and perhaps even hopeful or positive about imprisoned experiences, and his writing inspired imprisoned poets in the medieval and early modern periods.

Mimi Ensley

PhD Candidate

Department of English

University of Notre Dame

Footnotes

1. Quotations are taken from The Riverside Chaucer. For a more extensive discussion of Palamon and Arcite’s prison space, see V.A. Kolve, “The Knight’s Tale and Its Settings,” in Chaucer and the Imagery of Narrative (Stanford, CA: Stanford UP, 1984), 85-157.

2. Julia Boffey, “Chaucerian Prisoners: The Context of The Kingis Quair,” in Chaucer and Fifteenth-Century Poetry, eds. Julia Boffey and Janet Cowen (London: King’s College Centre for Late Antique and Medieval Studies, 1991), 84-103.

3. For details about the medieval Newgate, see Margery Bassett, “Newgate Prison in the Middle Ages,” Speculum 18.2 (1943): 233-46.

4. For one early modern prisoner’s experience building a reading and learning community in the Tower of London, see my article, “Reading Chaucer in the Tower: The Person Behind the Pen in an Early Modern Copy of Chaucer’s Works,” forthcoming in the Journal of the Early Book Society.

5. The TEAMS volume The Kingis Quair and Other Prison Poems is an excellent resource for these poets.

6. Mary-Jo Arn, “General Introduction,” in The Kingis Quair and Other Prison Poems, ed. Linne R. Mooney and Mary-Jo Arn (Kalamazoo, MI: Medieval Institute Publications, 2005).