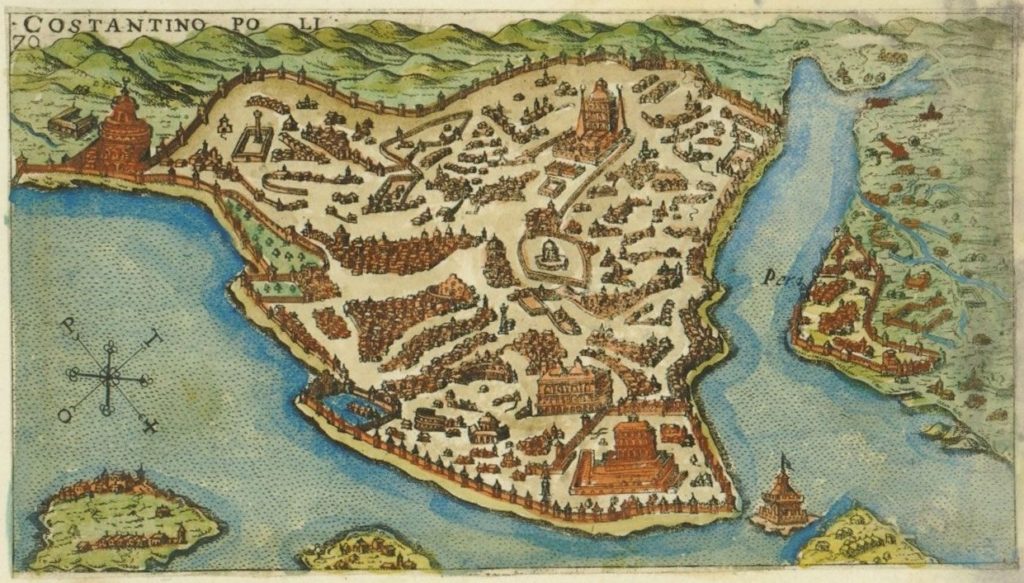

One of the questions that has long fascinated me is how human beings experience the spaces around them, and how those experiences are shaped, narrated, and transformed in literature. In the Byzantine world – stretching from 330, when Constantinople became the new capital of the Roman Empire, to 1453, when it fell to the Ottomans – literature was a window into these experiences, capturing how people imagined and interpreted space.

Among the many spaces that captured Byzantine imagination, few are as revealing as the prison. The narratives of Christian martyrs – stories inspired by the early Christian persecutions (first to fourth centuries) yet mostly composed during the Byzantine era – portray imprisonment not merely as suffering, but as a spiritual turning point. These texts recount the trials of devout men and women who were interrogated, tortured, imprisoned, and executed for refusing to renounce their faith. I first became deeply interested in this topic while examining how confinement was depicted in Byzantine hagiography, a line of inquiry that culminated in my monograph Gefängnis als Schwellenraum in der byzantinischen Hagiographie (Prison as a Liminal Space in Byzantine Hagiography, De Gruyter, 2021) . In this first part of a two-part blog, I return to that subject to explore the prison as a threshold space – one that mediates between human endurance and divine transformation.

Why start with martyrs? Among all genres of Byzantine literature, martyrs’ Passions – accounts of Christian martyrdom – offer the richest and most detailed depictions of imprisonment. These accounts were not only compelling to read but also deeply instructive, showing how imprisonment shaped a martyr’s journey toward holiness. In light of our own recent global experiences of confinement, such as during the COVID-19 pandemic, these medieval depictions of (in)voluntary isolation speak to us in new ways.

Prison as a Threshold

In martyr narratives, the prison is more than a location – it is a liminal space, a threshold between the human and the divine. After enduring brutal tortures, the martyr is thrown into a cell, often bloodied and near death. Conditions are harsh: hunger, thirst, vermin, filth, and extreme overcrowding challenge the body and spirit. Yet, the prison also becomes a space of transformation.

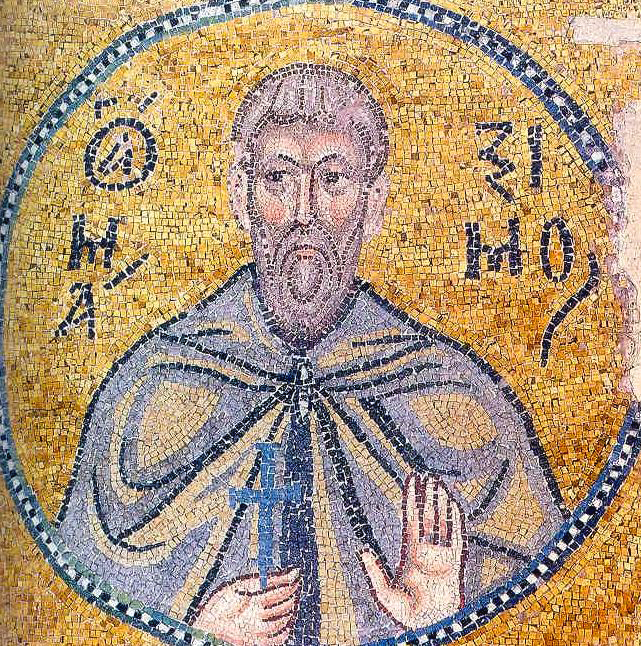

Inside these walls, martyrs pray fervently, and divine intervention is depicted in vivid ways. Christ or angels may appear to heal or strengthen them. Dreams and visions bring the imprisoned closer to God and the promise of Paradise. Simultaneously, martyrs often convert visitors and heal fellow prisoners, demonstrating that the prison is also a space of active spiritual engagement. It is here that martyrs begin to transcend their human limitations and move toward sanctity.

Sometimes, the narratives even hint at the possibility of escape, yet martyrs choose to remain. They understand imprisonment as a necessary step on the path to holiness, a phase through which they must pass to achieve ultimate communion with God.

Beyond Martyrs: Voluntary Confinement of Ascetics and Monks

While martyrs faced forced imprisonment, Byzantine literature also explores voluntary forms of confinement, particularly among ascetics and monastics. These individuals deliberately withdrew from society, seeking solitude in caves or cells to cultivate spiritual virtues. Here, too, the space of confinement is transformative.

The ascetic’s cell or cave is not a site of punishment, but of self-imposed discipline. The narratives show how sustained solitude shapes character, deepens devotion, and influences the progression of the story itself. By examining both involuntary and voluntary forms of confinement, we can see a continuum of experiences: whether imposed by external authorities or chosen freely, these spaces are intimately linked with personal and spiritual growth.

Why These Stories Matter Today

You might wonder: why should readers care about Byzantine martyr narratives today? Part of the answer lies in their timeless human themes. Confinement – whether imposed or voluntary – forces reflection, endurance, and transformation. In our contemporary world, moments of isolation, such as quarantine or personal retreat, echo the ancient experiences depicted in these texts. By understanding how Byzantines imagined and narrated confinement, we gain insight not only into a distant past but also into our own relationship with space, suffering, and growth.

Moreover, these texts offer a rare glimpse into the Byzantine worldview. Hagiographies – texts dedicated to the lives of saints – served multiple purposes: honoring saints, promoting veneration, instructing readers in moral and ethical behavior, and even entertaining them with vivid depictions of daily life, including violence and crime. In this sense, Byzantine hagiographies were a medieval form of “television,” engaging their audience on many levels.

The richness of these texts, preserved across centuries, allows scholars and enthusiasts alike to explore a world where physical spaces and spiritual journeys are inseparably intertwined. The prison is not simply a place of punishment; it is a threshold, a transformative environment, shaping human experience and bringing one closer to the divine.

In studying how Byzantines imagined confinement, we discover not only their mindset, but something essential about ourselves: the ways in which the human spirit turns limitation into transcendence.

Christodoulos Papavarnavas

Visiting Assistant Research Professor

Medieval Institute

University of Notre Dame