Today’s blog continues from last week’s discussion of the Nasrid College and the multicultural exchange it fostered in Medieval Iberia by shifting the focus to the intellectual and political.

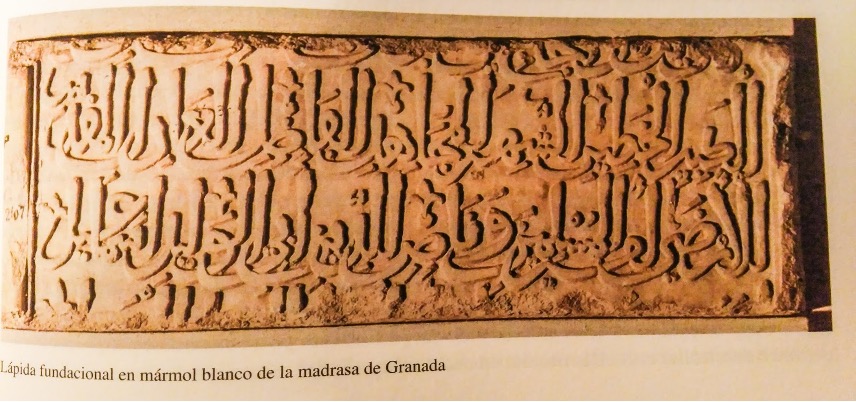

In Muḥarram 750/April 1349, the Nasrid College, located directly across from the former Great Mosque of Granada (today the cathedral) and near the main market, was completed.[1] It reflected the intersection between knowledge and power, cosmopolitanism and learning, in Nasrid Granada. Although the Nasrid College was certainly the most significant example of an Andalusi madrasah during the Middle Ages, the Granadan scholar-statesman and historian Lisān al-Dīn ibn al-Khaṭīb (d. 1374) states that “the admirable college was constructed during the reign of Yūsuf and was the most illustrious of all the colleges in his capital,” indicating that there may have been other such colleges in the kingdom.[2] The Nasrid College sought to establish the preeminence of the Granada as a leading intellectual and cultural center in the Islamic West. Its prominence reflected the transformation of Granada from an embattled frontier polity into a major center of learning in the Islamic West, competing with other intellectual centers such as Fez, Tlemcen, Tunis, Marrakesh and Meknes. Although law, Arabic grammar, and theology constituted the integral components of the curriculum, the subjects taught at the Nasrid College encompassed both the “traditional sciences” (al-‘ulūm al-naqliyyah) as well as the “philosophical sciences” (al-‘ulūm al-‘aqliyyah), and included jurisprudence, logic, medicine, astronomy, philosophy, mathematics, arithmetic, and geometry. Some of these subjects would also be studied with professors from the Nasrid College in other spaces in Granada, including the home and chancery. The students and teachers at the Nasrid College included some of the greatest luminaries from al-Andalus as well as North Africa during the 14th and 15th centuries. The Nasrid College contained a significant library that housed many of the most important works produced in the late medieval Islamic West, as well as many books from across the Islamic world. According to a note by the 15th-century Andalusi scholar Abū ‘Abd Allāh Muḥammad b. al-Ḥaddād al-Wādī Āshī, for example, an ornamented and calligraphic manuscript of the monumental “Comprehensive History of Granada” (al-Ihāṭah fī Akhbār Gharnāṭah, authored by Ibn al-Khaṭīb) was deposited in the library of Nasrid College during the reign of Muḥammad V (r. 1354-1359, 1362-1391), where it remained as an endowment (taḥbīs), and was consulted by subsequent generations of scholars.

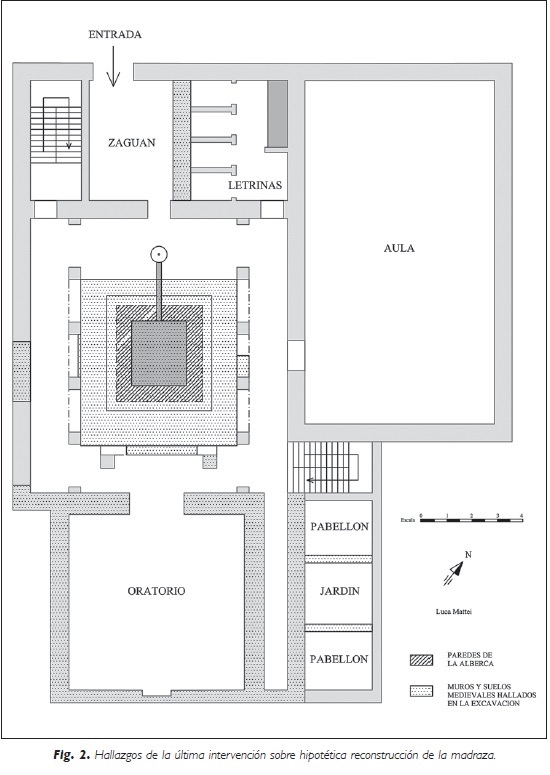

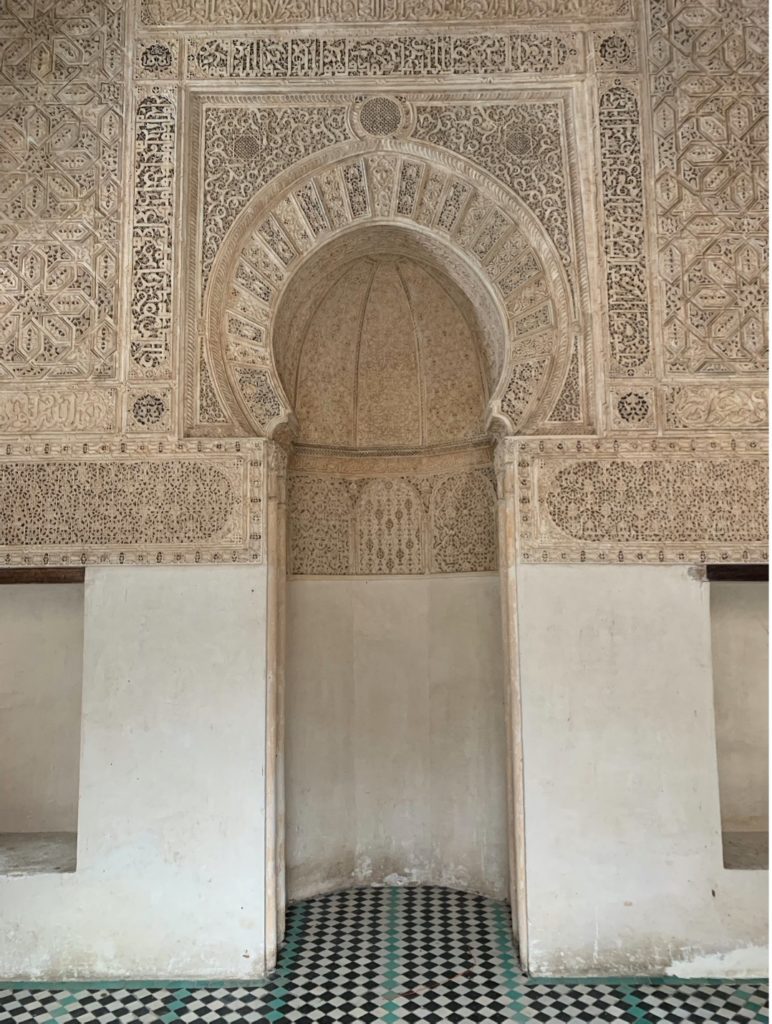

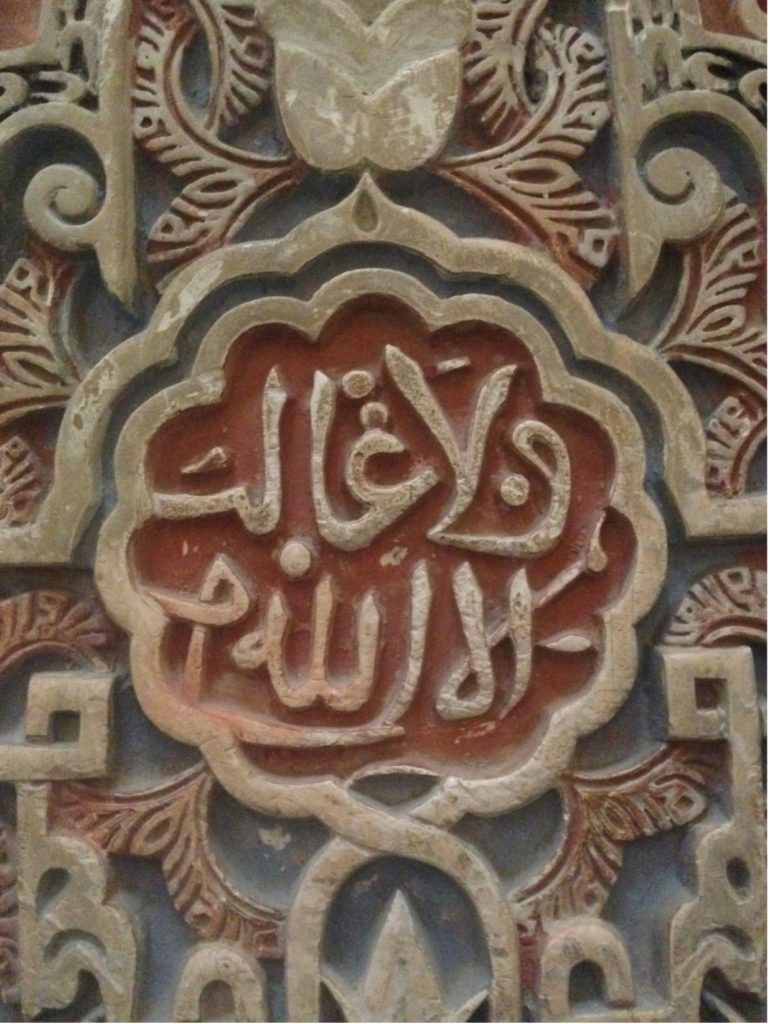

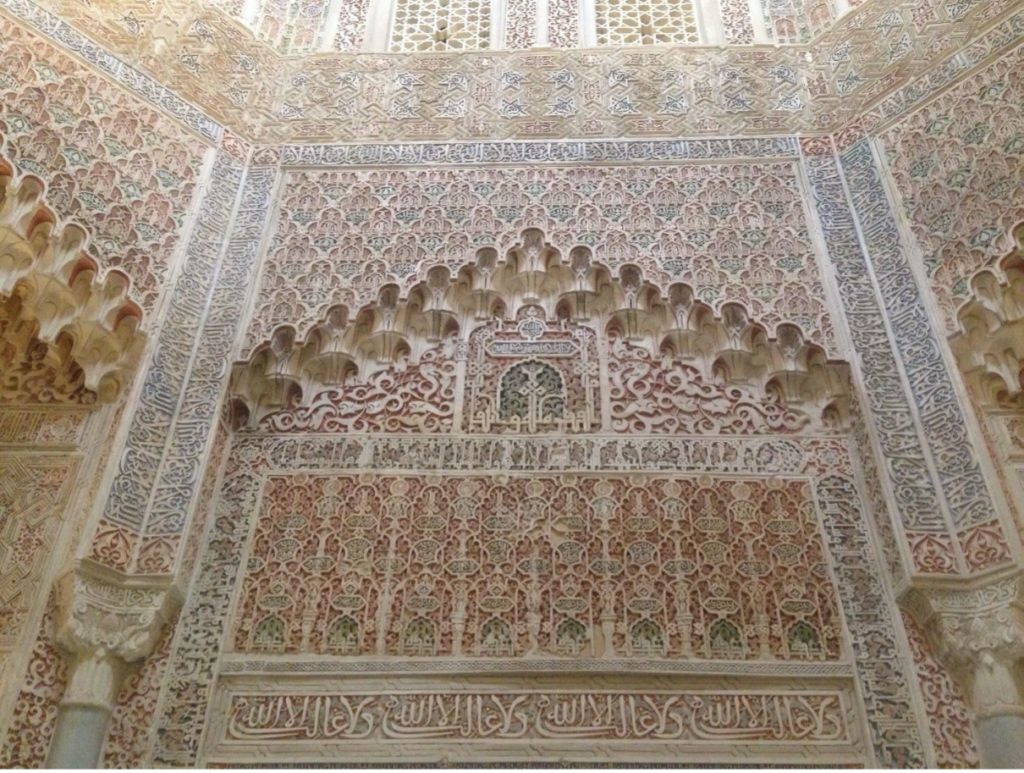

Following the Iberian Christian conquest of Granada in 1492, the Nasrid College survived largely intact, until much of it was demolished during the early 18th century to make way for a new Baroque structure. Although only the prayer niche (miḥrāb) and the Oratory of the Following the Iberian Christian conquest of Granada in 1492, the Nasrid College survived largely intact, until much of it was demolished during the early 18th century to make way for a new Baroque structure. Although only the prayer niche (miḥrāb) and the Oratory of the Nasrid College survives to the present day, recent studies by historians and archaeologists have sought to reconstruct the original structure, which included a monumental gate and pool.

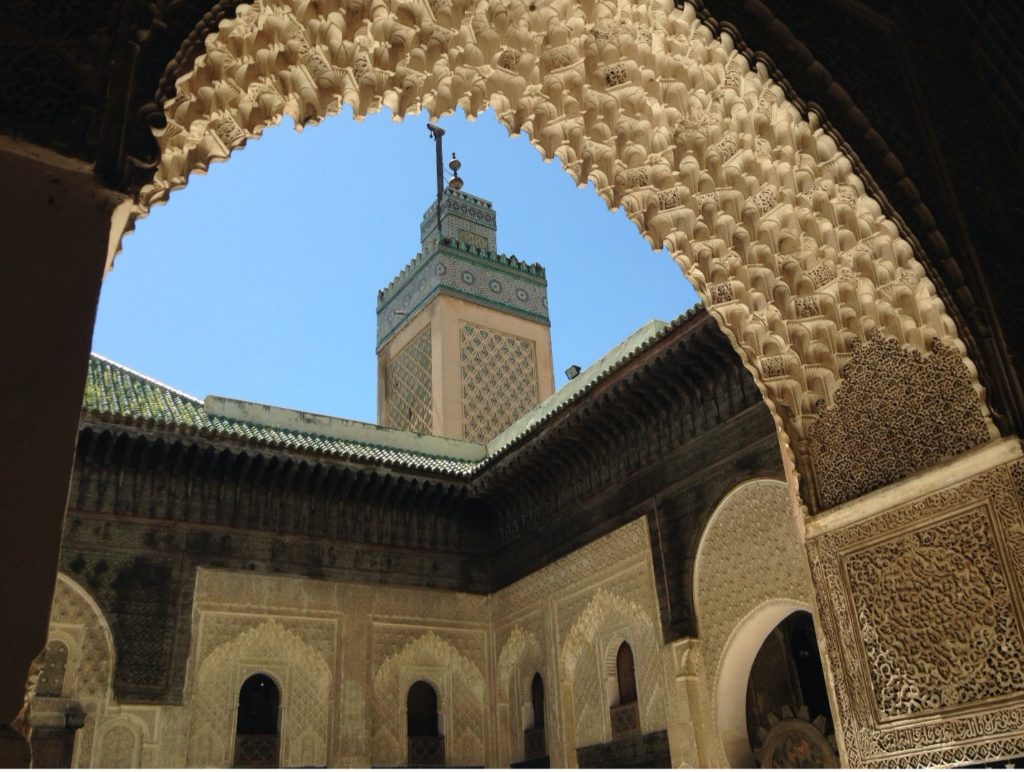

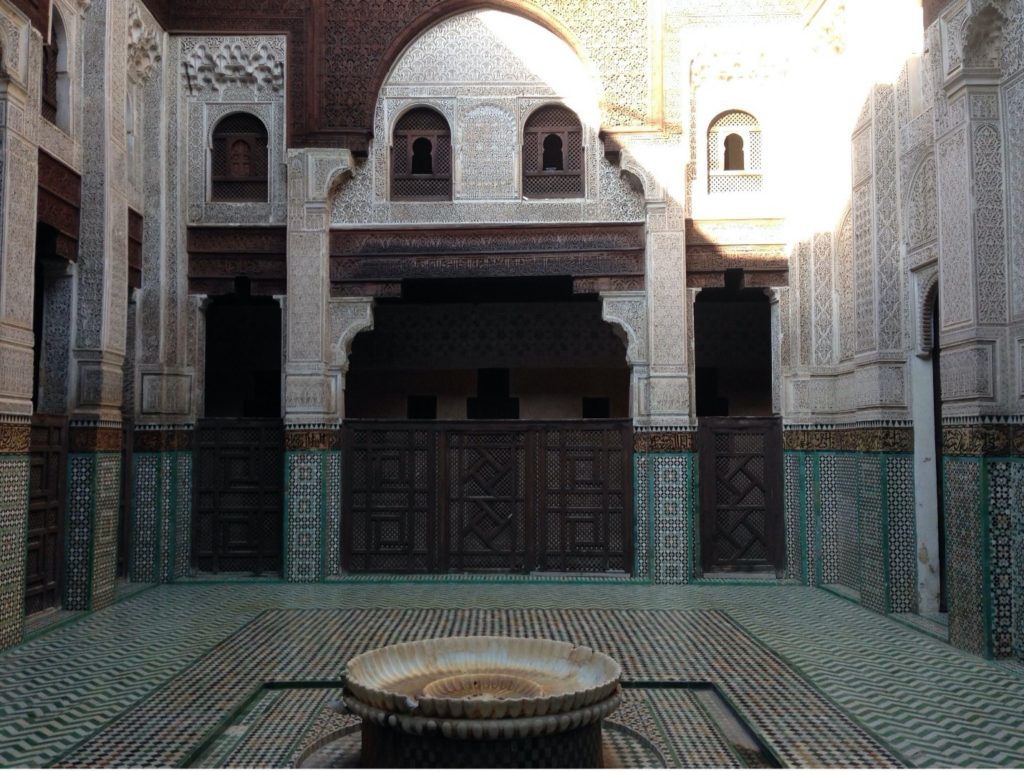

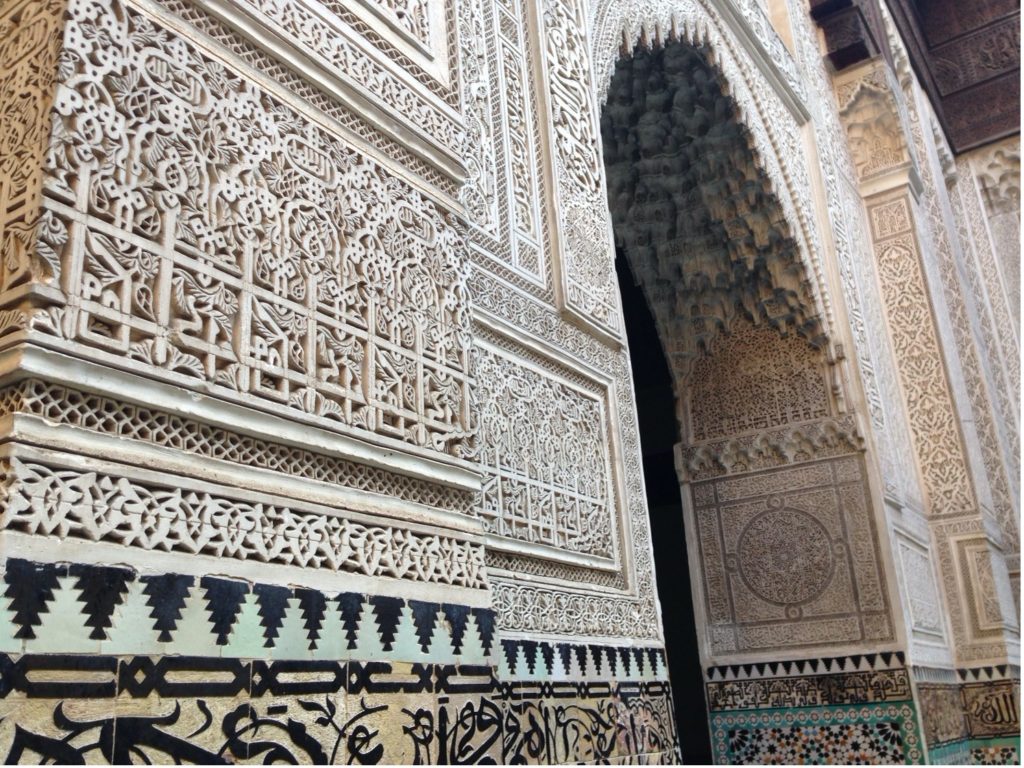

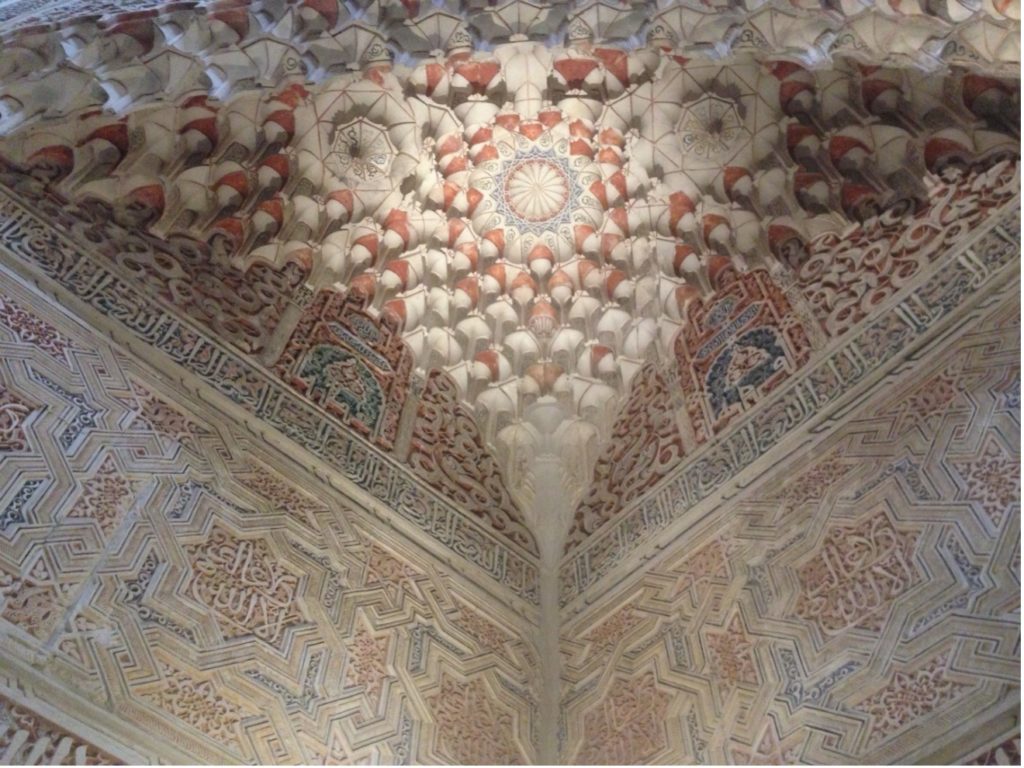

The survival of several contemporary Marinid colleges in North Africa, including those in Fez, Meknes, and Salé built during the 1340s and 1350s, may also provide an idea of both the scale and style of the Nasrid College.

Like the monumental colleges constructed by Marinid rulers in North Africa, especially Abū al-Ḥasan ‘Alī (r. 1331–1348) and Abū ‘Inān (1348–1358), this structure was intended to c

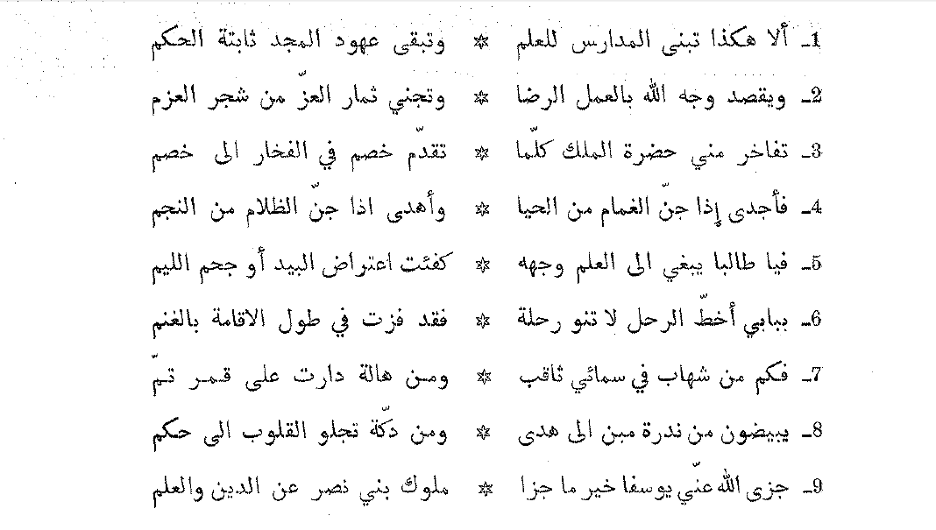

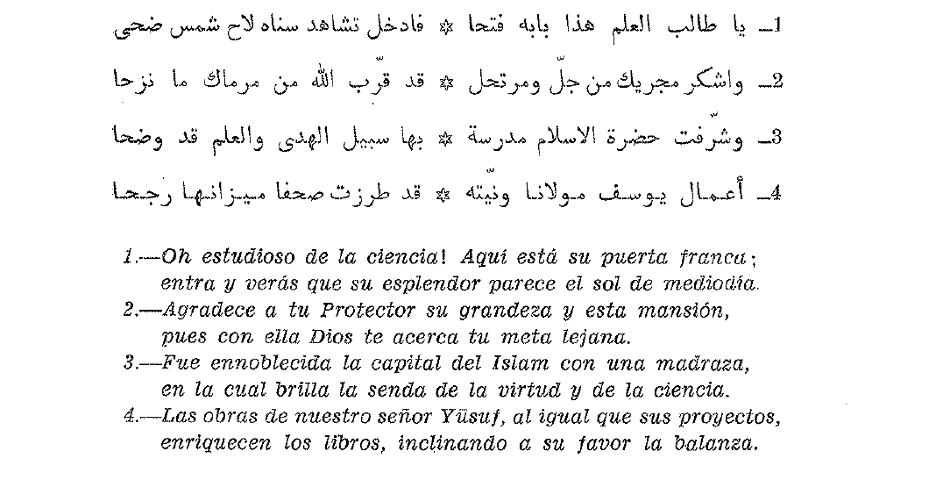

Like the monumental colleges constructed by Marinid rulers in North Africa, especially Abū al-Ḥasan ‘Alī (r. 1331–1348) and Abū ‘Inān (1348–1358), this structure was intended to celebrate the elaborate wealth and power of the sovereign, while proclaiming his commitment to knowledge. There are remarkable architectural and artistic similarities between the Nasrid College and other royal monuments in Granada, including the Alhambra, as well as with Marinid colleges in North Africa, particularly the College of Abū al-Ḥasan ‘Alī in Salé, which was built several years earlier. Similar to the Marinid colleges, the verses inscribed on the walls of the Nasrid College, which were preserved in medieval and early modern texts, were authored by leading scholars, litterateurs and courtiers. These celebrated the patronage of learning by Yūsuf I, and illustrate the interrelationship between royal power and learned elites in the Nasrid kingdom.[3]

In addition to reflecting a shared idiom of sovereignty and learned kingship across both Islamic Spain and North Africa, the similarities between these colleges, which were built within several years of one another, provides an important indication of the cultural and artistic exchange across the Islamic West. It also illustrates the role of interregional connections in strengthening the ties of affiliation and the diffusion of institutions between Iberia and North Africa during this period. Itinerant scholars, administrators and artisans served as cultural intermediaries and conduits for the exchange of ideas and institutions between Nasrid Granada and Marinid Morocco. The Nasrid College was merely one illustration of this broader phenomenon.

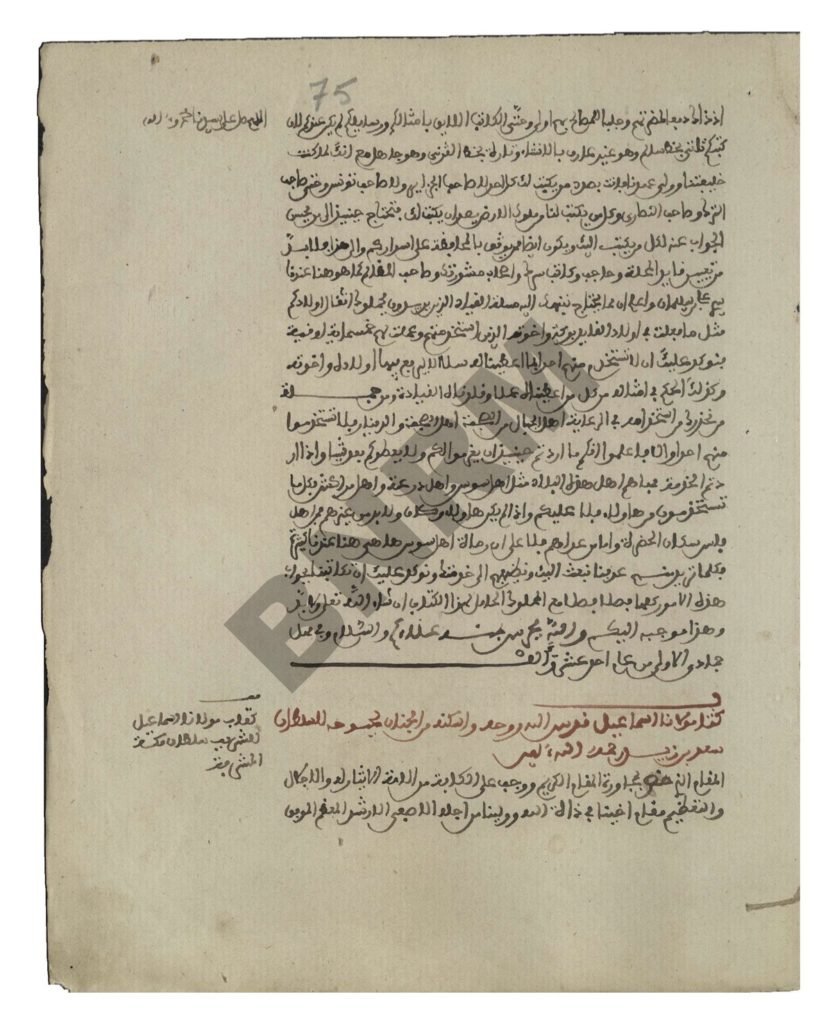

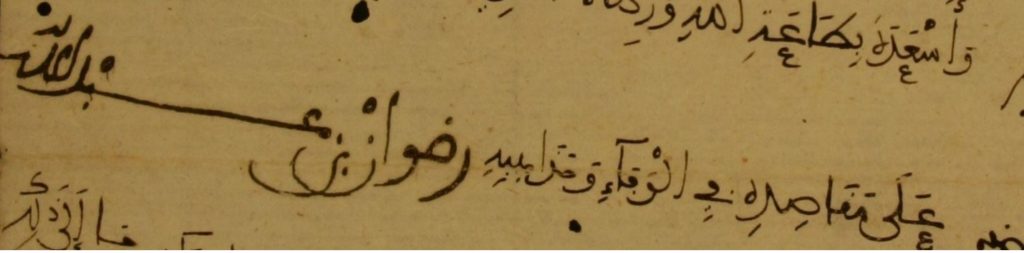

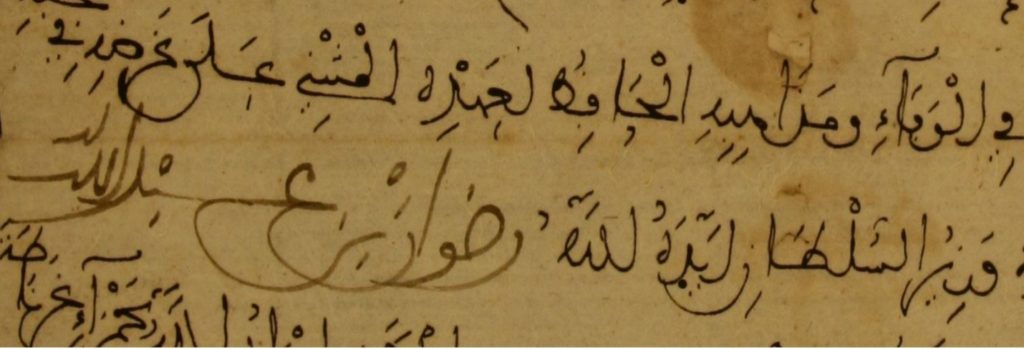

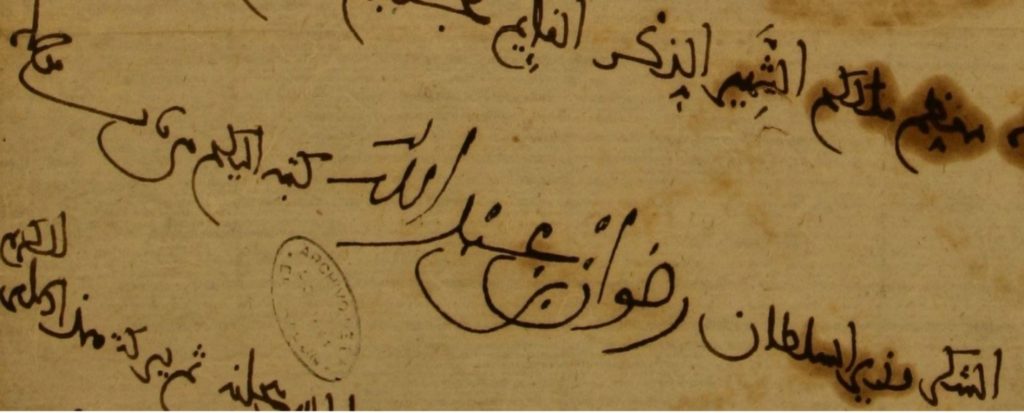

While the College came to be known in later sources as al-Madrasa al-Yūsufiyya or “The College of Yūsuf,” and came to be associated with the name of Yūsuf I (r. 1333-1354), it was in fact the creation of Abū Nu‘aym Riḍwān al-Naṣrī (d. 1359), this Nasrid sovereign’s royal chamberlain.[4] Abū Nu‘aym Riḍwān was a prominent example of a particular class of Nasrid society that modern scholarship has referred to as “renegades,” enslaved people and freedmen and their descendants who were an integral part of Granada’s population. Riḍwān was born into a Castilian Christian family in Calzada de Calatrava before being enslaved as a child during a Nasrid raid in the late 13th century. Following his captivity, he was converted to Islam and manumitted, received an education in the Nasrid court, and eventually appointed to leading positions of executive authority, including royal chamberlain, chief minister and commander of the military. The rise to prominence of Riḍwān during this period is also corroborated by contemporary Castilian and Aragonese sources, including the Crónica de Alfonso XI, which describes him as “a Muslim knight known as Reduan, the son of a Christian man and Christian woman, whom the king of Granada trusted immensely (un cavallero moro que dezian Reduan que fuera fijo de christiano e de christiana e era ome quien fiava mucho el rey).”[5] There is substantial evidence that Riḍwān served as an intermediary with the Iberian Christian kingdoms, and corresponded directly with Alfonso IV (r. 1327–1336) and Pedro IV (r. 1336–1387) of Aragón in order to secure a peace treaty between the Nasrids and Aragón. In these documents, four of which have been preserved in the Archivo de la Corona de Aragón, Riḍwān consistently refers to himself as “Riḍwān, son of God’s servant, the chief minister of the Sultan” (Riḍwān ibn ‘Abd Allāh wazīr al-sulṭān).

Alongside his prominent role in politics, diplomacy and administration, Riḍwān was also among the most important patrons of scholars and learning within Nasrid Granada. According to the Granadan scholar-statesman Ibn al-Khaṭīb, one of the beneficiaries of Riḍwān’s patronage, the latter invested considerable funds into a pious endowment (waqf),[6] which formed the foundation of the College’s existence (and stipends for its students), personally financed its decoration and ornamentation, and linked it with the urban system of waterworks to ensure it had a steady supply of water from the river.[7] Such details enable us to appreciate the role of the endowment, or waqf (pl. awqāf), as one of the avenues in which scholar-officials and palace functionaries, particularly upwardly-mobile ones, invested their wealth to leave their imprint on the kingdom. The construction of the Nasrid College, in addition to fortifications and mosques by Riḍwān, demonstrates how his own personal wealth, accumulated over decades while in royal service, played an important role in developing the urban space of Granada. The centrality of a Castilian-born freedmen in the emergence of Granada’s most important institutions of learning illustrates the ways in which the Nasrid College embodied the intersection of traditions of learning, notions of sovereignty and borderland realities in Nasrid Granada.

This concerted program of urban expansion and elaborate construction in Granada during the 14th century was accomplished through the close collaboration between the secretarial class, nobles, artisans, and craftsmen. The establishment of the Nasrid College and its transformation into one of the most important institutions of learning in Granada was made possible by the close relationship between the sovereign, leading statesmen such as Riḍwān and the various secretaries and functionaries within the Nasrid chancery. The construction of the Nasrid College and the circumstances surrounding it demonstrate that, far from being a period of “intellectual decline,” the 14th and 15th centuries in the Islamic West witnessed the emergence of a rigorous scholarly culture that produced brilliant individuals and prolific scholars. The Nasrid College, which has now become the subject of numerous interdisciplinary studies that have included historians, philologists, and archaeologists, has the potential to shed light on this larger cultural renaissance.

Mohamad Ballan

Mellon Fellow, Medieval Institute

University of Notre Dame (2021-2022)

Assistant Professor of History

Stony Brook University

Further Reading

Abu Rihab, Muhammad al-Sayyid Muhammad. al-Madāris al-Maghribīyah fī al-ʻaṣr al-Marīnī : dirāsah āthārīyah miʻmārīyah. Alexandria: Dār al-Wafāʼ li-Dunyā al-Ṭibāʻah wa-al-Nashr, 2011.

Acién Almansa, Manuel. “Inscripción de la portada de la Madraza.” Arte Islámico en Granada, pp. 337-339. Granada, 1995.

Al-Shahiri, Muzahim Allawi. al-Ḥaḍārah al-ʻArabīyah al-Islāmīyah fī al-Maghrib : al-ʻaṣr al-Marīnī. Amman: Markaz al-Kitāb al-Akādīmī, 2012

Bennison, Amira K ed. The Articulation of Power in Medieval Iberia and the Maghrib. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2014.

Buresi, Pascal and Mehdi Ghouirgate. Histoire du Maghreb medieval (XIe–XVe siècle). Paris: Armand Colin, 2013

Cabanelas, Dario. “La Madraza árabe de Granada y su suerte en época cristiana,” Cuadernos de la Alhambra, nº 24 (1988): 29–54

________. “Inscripción poética de la antigua madraza granadina” Miscelánea de Estudios Árabes y Hebraicos Sección Árabe-Islam 26 (1977): 7-26.

Ferhat, Halima. “Souverains, saints, fuqahā’.” al-Qantara 18 (1996): 375–390

Harvey, Leonard Patrick. Islamic Spain, 1250–1500. Chicago, University of Chicago Press, 1990

Le Tourneau, Roger. Fez in the Age of the Marinides. University of Oklahoma Press, 1961

Makdisi, George. “The Madrasa in Spain” http://www.persee.fr/web/revues/home/prescript/article/remmm_0035-1474_1973_num_15_1_1235

Mattei, Luca. “Estudio de la Madraza de Granada a partir del registro arqueológico y de las metodologías utilizadas en la intervención de 2006.” Arqueología y Territorio 5 (2008): 181-192

Prado García, Celia. “Los estudios superiores en las madrazas de Murcia y Granada. Un estado de la cuestión.” Murgetana 139 (2018): 9-21.

Rodríguez-Mediano, Fernando. “The Post-Almohad Dynasties in al-Andalus and the Maghrib.” In The New Cambridge History of Islam, Volume II: The Western Islamic World, Eleventh to Eighteenth Centuries, edited by Maribel Fierro, pp. 106–143. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2012.

Rubiera Mata, María Jesús. “Datos sobre una ‘Madrasa’ en Málaga anterior a la Naṣrí de Granada.” Al-Andalus 35 (1970): 223–226

Sarr, Bilal and Luca Mattei. “La Madraza Yusufiyya en época andalusí: un diálogo entre las fuentes árabes escritas y arqueológicas.” Arqueología y Territorio Medieval 16 (2009): 53–74.

Secall, M. Isabel Calero. “Rulers and Qādīs: Their Relationship during the Naṣrid Kingdom.” Islamic Law and Society 7 (2000): 235–255

Seco de Lucena Paredes, Luis. “El Ḥāŷib Riḍwān, la madraza de Granada y las murallas del Albayzín.” Al-Andalus 21 (1956): 285–296.

Simon, Elisa. “La Madraza Nazari: Un centro del saber en la Granada de Yusuf I.” https://andalfarad.com/la-madraza-nazari/

[1] The most important scholarship about the Nasrid College includes La Madraza: pasado, presente y futuro (Granada: Editorial Universidad de Granada, 2007), eds. Rafael López Guzmán and María Elena Díez Jorge; La Madraza de Yusuf I y la ciudad de Granada: análisis a partir de la arqueología (Granada: Editorial Universidad de Granada, 2015), eds. Antonio Malpica Cuello and Luca Mattei.

[2] Ibn al-Khatīb, al-Lamḥa al-Badriyya fī al-Dawla al-Naṣriyya (Kuwait, 2013), p. 153. For a discussion of an earlier college built in the Nasrid kingdom, see María Jesús Rubiera Mata, “Datos sobre una ‘Madrasa’ en Málaga anterior a la Naṣrí de Granada,” Al-Andalus 35 (1970), pp. 223–226.

[3]Darío Cabanelas, “Inscripción poética de la Antigua madraza granadina,” Miscelánea de Estudios Árabes y Hebraicos, Sección Árabe-Islam 26 (1977), pp. 7–26.

[4] For an overview of this figure’s life and career, see Luis Seco de Lucena Paredes, “El Ḥāŷib Riḍwān, la madraza de Granada y las murallas del Albayzín,” Al-Andalus 21 (1956), 285–296.

[5] Fernán Sánchez de Valldolid, Crónica de Alfonso XI, BN MS 829, ff. 190r–190v.

[6] For a comprehensive study of awqāf in al-Andalus, see Alejandro García-Sanjúan, Till God inherits the Earth: Islamic Pious Endowments in al-Andalus (9-15th centuries) (Leiden: Brill, 2007).

[7] Ibn al-Khaṭīb, al-Iḥāṭa, 1: 508–509.