“You should look into Hoccleve.”

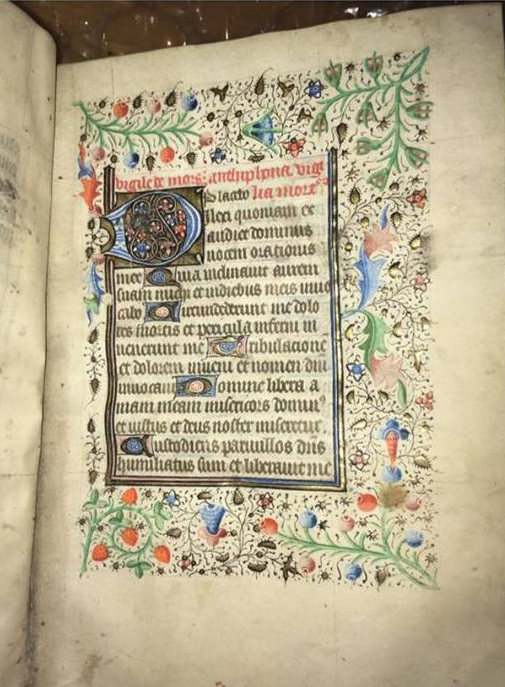

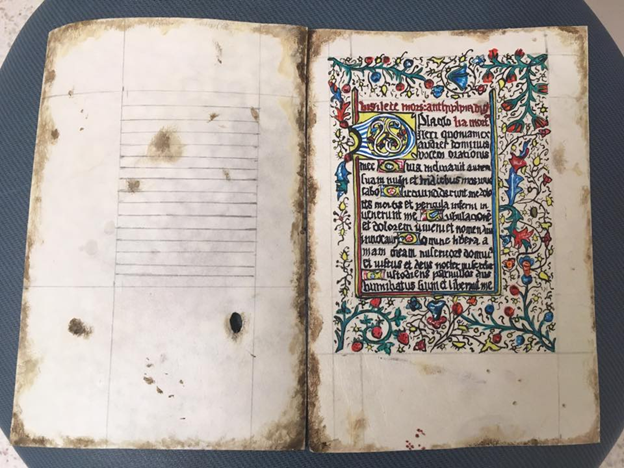

These words changed everything about the way I looked at London, British Library MS Harley 219. I’d been working with this volume of primarily Latin and French texts for several years, focusing on Christine de Pizan’s Epistre Othea [Letter of Othea], a popular advice text, which Christine claims draws on a letter from Othea, the goddess of wisdom and prudence, to Hector of Troy.

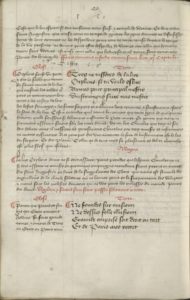

Harley MS 219 is – to put it bluntly – a weird manuscript, one that had always bothered me because it is the only complete manuscript of the Othea with a dedication to Henry IV of England. Yet it is far from a luxury copy – how did the text travel from a manuscript fit for a king to this rather lackluster volume?

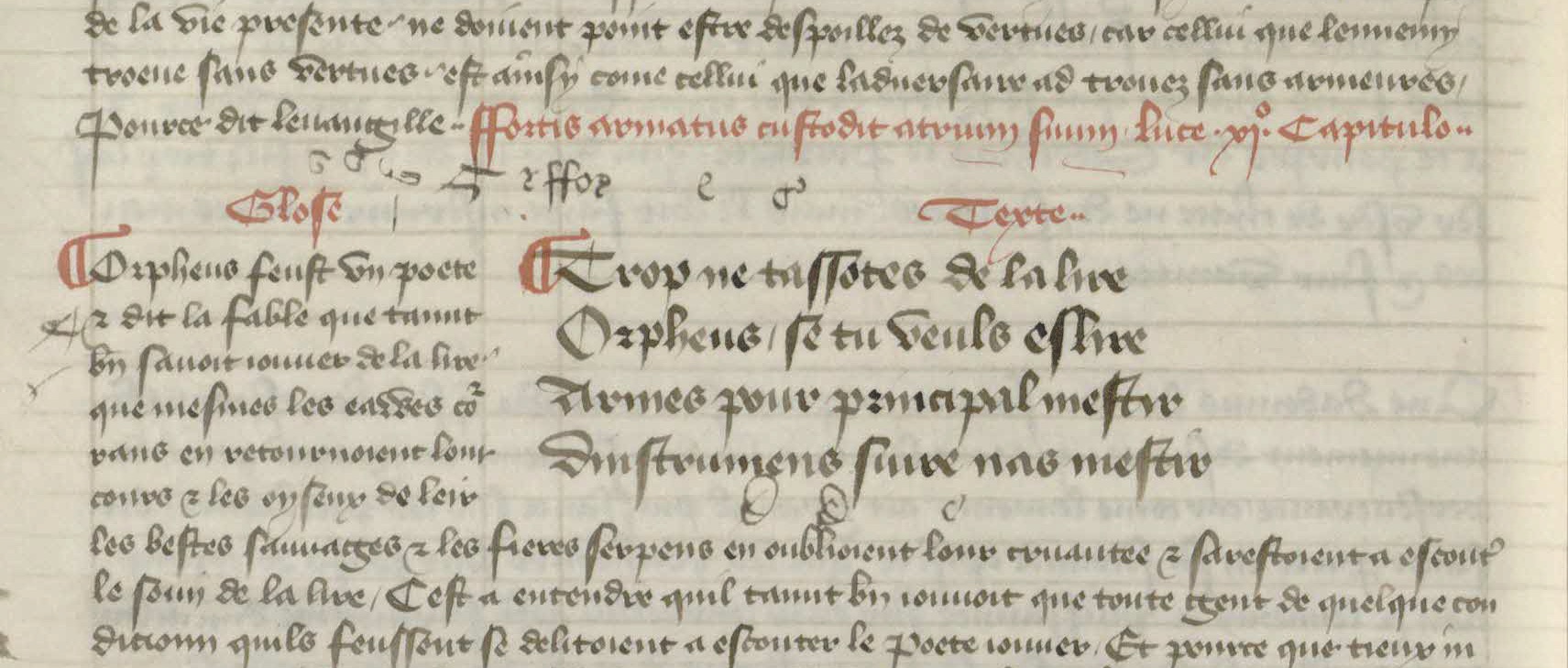

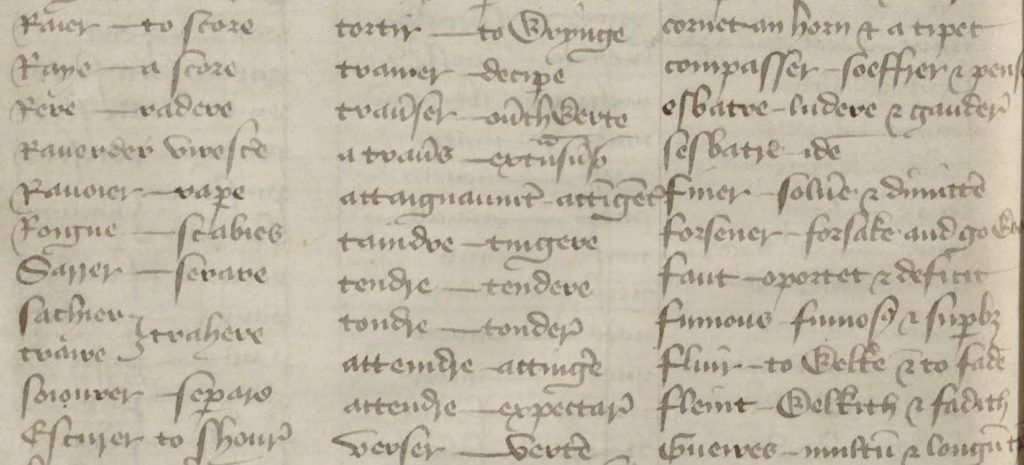

Immediately after the Othea, there is a glossary of French terms into Latin and, less often, Middle English that has fascinated me. Some content is standard for glossaries of the time – words with double meanings, body parts, animals, occupations, tools, family members, and such. Some entries may directly draw on vocabulary in the Othea, essentially providing a practical aid to assist an English reader with the French language.[i] The final folio contains a series of phrases in French then English ranging from the expected, like “wype your hands,” to the bizarre, such as “the body is withynne the tombe” and “this is an hyred hors.” Some phrases were clearly added later by the same scribe who produced the Othea and glossary. Aspects of this scribe’s handwriting tugged at my brain: from my paleography classes, I knew that w– and this circular one in particular – was an important feature and might help me identify the scribe. Yet this was not my main project, and I could only justify spending a little time on the glossary for a short paper on fifteenth-century Anglo-French at the New Chaucer Society conference.

I included images of the glossary in my talk, and I could scarcely suppress a wry smile when a friend asked about the scribe and the manuscript’s history. These were the crucial questions, as they are so often for manuscripts whose scribes and readers are unknown. I relayed what little was known: it was produced in England, dated to the late fifteenth century, and the French texts show Anglo-Norman spellings. My friend, who has done significant research on Thomas Hoccleve and documents produced in the Royal Office of the Privy Seal (which wrote letters for the King), noted characteristics of Privy Seal clerk handwriting, and advised, “You should look into Hoccleve – it could even be him.”

The room buzzed at the possibility, with some audience members agreeing and at least one expressing doubt. If we had been in a cartoon, the light bulb above my head would have come on: that is why the w was troubling me – it is one of Hoccleve’s characteristic letter forms (though by no means unique to him). And crucially, Hoccleve’s connections to the King would explain the mystery of the Harley MS 219 Othea’s origins. Scholars accept that Hoccleve translated Christine’s Epistre de dieu d’amours into The Letter of Cupid (1402) from a copy in Henry’s possession, making the same path of transmission conceivable for Henry’s Othea to Hoccleve.[ii]

Of course, I only articulated these ideas in print after painstaking comparison of iconic Hoccleve letter forms – figure-eight A, flat-headed g, circular w, self-dotting y, and tilted h– with those in Harley MS 219.[iii] At several points, I stepped back to ensure I wasn’t guilty of simply wanting this to be Hoccleve’s handwriting, which led to a fair amount of double- and triple-checking. In the end, significant evidence suggests that Hoccleve – one of the most prominent English poets after Chaucer – is indeed the scribe who copied the Epistre Othea and glossary into Harley MS 219.

Linking Harley MS 219 to Hoccleve shifts radically our understanding of the manuscript, its Othea, and Hoccleve’s sources for his original poetry (more on the latter in part 2). The manuscript had been dated to 1475, based on stylistic features of another text. However, since Hoccleve died in 1426, and his handwriting appears throughout the majority of the volume, the manuscript must be dated before then. I suggest early fifteenth century, near Hoccleve’s translation of the Letter of Cupid and close to Henry’s receipt of the original, sent to him around 1401-02, according to Christine’s own account.[iv]

The Harley MS 219 Othea has rarely received interest from scholars, in part for its Anglo-Norman spellings. Yet even with spelling differences, minor scribal variants, and some disordered chapters (likely due to disorder in Hoccleve’s source), this manuscript deserves renewed attention and more authority. Hoccleve was no bumbling Anglo-Norman scribe; he was a practiced clerk who used French daily in his occupation. His French may not be of the Continent, but it is certainly competent, and we can plausibly construct a direct line from this copy to Henry’s original.[v]

Of course, questions remain, namely, who were the readers and what was the purpose for this volume? It seems likely that the audience would have been other educated clerks who enjoyed literary material, and the volume may be evidence for a literary circle for Hoccleve and his colleagues. There are two indicators that the audience must have been educated: the main texts are in Latin and French, and the glossary uses Latin more often than English to translate French words. Readers would have to know Latin to appreciate the narratives and even use the glossary.

My proposal that enjoyment may have been a purpose for the volume stems largely from external evidence in Hoccleve’s poetry and from the glossary. In the Series, Hoccleve claims that his friend must bring him the concluding moralization to a narrative he has been writing. In Harley MS 219 that particular story is complete, but another lacks the moral, and in the copying and codicology of a wider set of tales, one quire (bundle of pages) ends with a blank folio (page); it is followed by an additional quire in a different hand, as if a friend or colleague did indeed add a missing section Hoccleve’s volume needed.

Additionally, the glossary has – I think – more than one “inside joke” for readers familiar with Hoccleve and his poetry, but I will hold myself to only one example. The phrasebook in particular conveys Hoccleve’s playfulness in producing it, especially the unexpected “this is an hyred hors” (fol. 151v), which seems a strange inclusion. Surely proclaiming that one has rented his mode of transportation could not be a significant necessity abroad.

Yet this phrase calls to mind Hoccleve’s analogy for an inconstant woman in Letter of Cupid: “Shee for the rode of folk is so desyrid, / And as a hors fro day to day is hyrid” (102-3). This must be an inside joke for Hoccleve’s friends, and the manuscript as a whole may suggest evidence for the sort of circle of literate friends that Hoccleve imagines in the Series and in one of his ballads for Henry Somer (who worked in high positions in the English Treasury) that depicts a lively dining club whose members may have appreciated literary texts in all three of the languages present in Harley MS 219, Latin, French, and English.

But the importance of the discovery of Hoccleve’s involvement in the production of Harley MS 219 goes much further when we enlarge the scope of our inquiry beyond the Othea and glossary to find Hoccleve participating in the production of other texts in the volume, two of which were major sources for his original compositions.

Click here to read Part 2.

Misty Schieberle, PhD

University of Kansas

About the Author: Misty Schieberle is Associate Professor of English at the University of Kansas, currently completing an edition of the Middle English translations of Christine de Pizan's Epistre Othea and continuing her work on Harley MS 219, including an edition of the glossary.

[i]Stephanie Downes, “A ‘Frenche booke called the Pistill of Othea’: Christine de Pizan’s French in England,” in Jocelyn Wogan-Browne et al. (eds), Language and Culture in Medieval Britain: The French of England c.1100–1500(York, 2009), 457–68, at 461–5, notes how the glossary seeks to educate the reader in various aspects of the French language, including verb tenses and terms relevant to the Othea.

[ii]On which, see James C. Laidlaw, ‘Christine de Pizan, the Earl of Salisbury and Henry IV’, French Studies, 36 (1982), 129-43.

[iii]See H. C. Schulz, ‘Thomas Hoccleve, Scribe’, Speculum, 12 (1937), 71–81; Thomas Hoccleve: A Facsimile of the Autograph Verse Manuscripts, introd. J. A. Burrow and A. I. Doyle, EETS s.s. 19 (Oxford, 2002), xxiv-xxxvii. My own article, “A New Hoccleve Literary Manuscript: The Trilingual Miscellany in London, British Library, MS Harley 219” will appear in Review of English Studies in November 2019, and it is currently available online for advanced access subscribers: https://academic.oup.com/res/advance-article-abstract/doi/10.1093/res/hgz042/5510111

[iv]Christine de Pizan, The Vision of Christine de Pizan, trans. Glenda McLeod and Charity Cannon Willard (Cambridge, 2005), 106-7.

[v]The Harley MS 219 Othea’s chapters go from 86 to 93-98 and back to 87 over the course of fols. 142r-144r, without a break in quire structure, which suggests that Hoccleve’s source had a misplaced quire. Thus, there could be an intermediary between this manuscript and Henry’s original, though that is not strictly necessary – Henry’s own copy could have been misfoliated at some point.