The Republic, The Symposium, The Phaedrus, The Apology, and The Phaedo––these are just a few of the works of Plato that were not widely available throughout most of the Middle Ages. No extended depiction of the most just city in the Republic. No discussion of love in The Symposium and The Phaedrus. No self-defense for Socrates at his trial as found in The Apology, and no final dialogue before his suicide as found in The Phaedo. For lovers of great texts, especially Plato, such news can be shocking. What kind of Plato does a person know if they don’t have these key works? How much of Socrates’ life and Plato’s philosophy could even be known? These are the questions that many medieval scholars of the Latin Platonist tradition have dedicated their lives and careers to answering, and the answers can be quite surprising.

One aspect of this research that ought to be appreciated by the wider reading public (outside of the narrow confines of medievalists) is that Plato’s Timaeus wasthe most widely available Platonic work throughout most of the Middle Ages. In fact, examining the text of the Timaeus and why itwas such one of the few Platonic texts preserved reveals how peculiarly modern our current canon of Platonic literature is.

What we value in Plato was not necessarily what late antique or medieval readers valued, and yet, their ability to read well meant that they understood a lot more than might be supposed. An attention to the reception history of Plato’s Timaeus can give modern readers of Plato a better appreciation for the importance of both mathematics and poetry in Platonic philosophy.

The Timaeus is Plato’s work on the origins of the universe. It begins with a dialogue between Timaeus, Socrates, Hermocrates, and Critias, in which Socrates expresses a desire for a “moving image” of the city they had been talking about the day before. The summary of the previous day’s discussion appears to bear some resemblance to the conversation found in the Republic although scholars are divided over whether this summary perfectly matches the Republic that we now possess. Regardless of its accuracy, this summary would have been the closest a medieval reader would have had to a taste of the Republic. The opening dialogue covers all sorts of fascinating topics from Solon’s visit to Egypt, oral culture, the mythic origins of writing, and the myth of Atlantis, but the bulk of the work features a narration about the origins of the universe recounted by the Pythagorean, Timaeus.

The Timaeus was received in the Middle Ages through three main channels of Latin translations: the translation of Calcidius (which ends at 53b), the translation of Cicero (available but not widely used or even known, which ends at 42b), and the excerpts from the Ciceronian translation of the Timaeus that can be found in Augustine’s City of God. Although it does not contain the whole text of the Timaeus, Calcidius’ translation is much more complete than Cicero’s: rather than giving merely the speech of Timaeus like Cicero’s translation does, it includes the opening dialogue (even though the commentary itself ignores it).

Most modern Plato scholars would probably not choose The Timaeus as theone and only work they could save from destruction for all time. But, a better understanding of who Calcidius was and why he wrote the commentary on the Timaeus suggests that the preservation of the Timaeus in the Latin West was not an accident of fate. Rather, the results of Gretchen Reydams-Schills’ lifelong study of Calcidius give a plausible reason for why Calcidius’ commentary may have been the Platonic work of choice for many late antique philosophers.

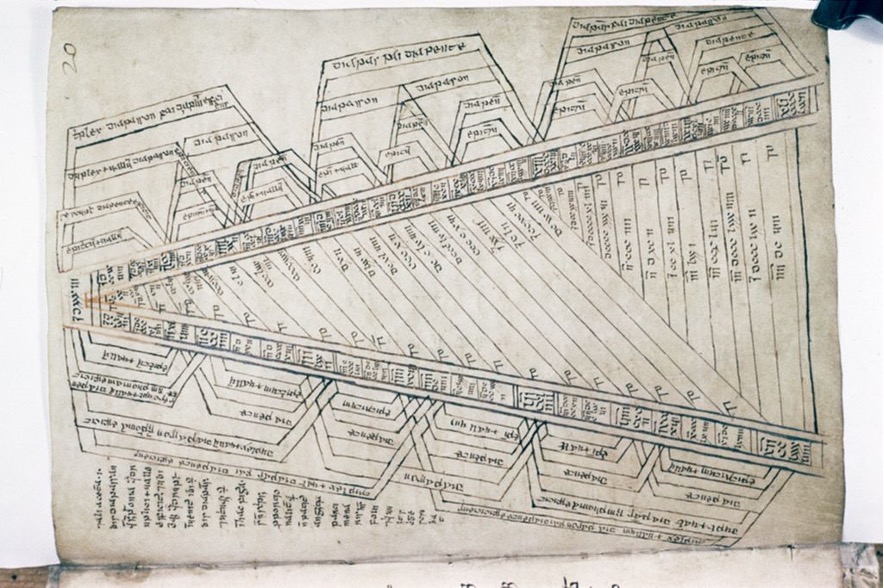

Reydams-Schils argues that Calcidius wrote his commentary as an introduction to the Platonic corpus, essentially reversing the Middle Platonic curriculum, which traditionally ended with the Timaeus. One major piece of evidence for this theory is that Calcidius’ commentary often reserves discussion of harder philosophical concepts for the end of the commentary.Furthermore, unlike the Neoplatonists, Calcidius did not read the Timaeus synoptically and believed strongly in the importance of sequential reading of the Platonic corpus. In Calcidus’ Platonic curriculum, the Timaeus came first with its teachings on natural justice, then the Republic with its teaching of positive justice, and finally, the Parmenides came with its teaching of the forms and intelligible realities. Calcidius believed that a thorough understanding of mathematics was necessary for understanding of almost all of the Platonic works, which is why his commentary on the Timaeus turns out to be something like a crash course in Pythagorean mathematics.

Thus, although the Timaeus was one of the only Platonic works available throughout the early Middle Ages, Calcidius’ commentary gave readers some introduction to the entire Platonic corpus as well as a great deal of Pythagorean mathematics. Perhaps there might be good reason for a philosopher to save The Timaeus (especially a copy with Calcidius’ commentary)from a burning building!

Medievalists who study the textual reception of the various translations of The Timaeus have been able to identify a shift in kinds of interest in Plato over time. The primary Latin translation of the Timaeus used until the eleventh century was Cicero’s. Medieval scholars used to assume that the revival of Calcidius began with the twelfth century Platonists, but Anna Somfai has demonstrated that the proliferation of copies of Calcidius’ text and commentary began in the eleventh century when championed by Lanfranc of Bec (c.1050). The late twelfth-century actually experienced a decline of copying the Timaeus as interests shifted towards other texts.

What motivated the eleventh-century interest in Calcidius appears to have been the mathematical content of the Calcidian commentary because, by the Carolingian period, much of the actual content of the quadrivial arts had been lost, and scholars in the Middle Ages attempted to piece together what scraps of it remained from a variety of sources. Calcidius’ commentary on the Timaeus appears to have been particularly valued as a source text for the quadrivial (or mathematical) arts. As my two previous MI blogs have explored here and here, medieval thinkers in the traditional liberal arts tradition recognized that the quadrivial arts were the foundation for philosophical thought, even if they had few textual sources for actually studying them.

And although some of the interest in the kinds of mathematics found in the Timaeus and Calcidius’ commentary may have declined after the twelfth century, it was by no means lost completely. As David Albertson has demonstrated, the mathematical interest in Plato found in the work of the twelfth-century scholar, Thierry of Chartres, would eventually be picked up by the fifteenth-century scholar, Nicholas of Cusa, and many scholars have noted resonances of Cusa’s quadrivial agenda in the thinking of Leibniz, the founder of calculus:

It seems that God, when he bestowed these two sciences [arithmetic and algebra] on humankind, wanted to warn us that a much greater secret lay hidden in our intellect, of which these were but shadows. (Leibniz as quoted by Albertson, p.2)

Even though the interest in scribal copying of the Timaeus seems to have declined somewhat by the twelfth-century, another kind of imitatio or translatio studii was being enacted by a different kind of scholar, Bernard Silvestris. He wrote a prosi-metric telling of the creation of the world that emulates Plato’s Timaeus. The title of his work, Cosmographia, roughly translates as “universe writing,” and Bernard delivered an oral performance of itbefore Pope Eugenius III in 1147. Bernard’s creative retelling of the Timaeus poetically depicts the role of imitation in the divine creation of the world in the form of “divine writing.” Performatively, the Cosmographia demonstrates that this divine writing is then imitated by poets in the form of human writing. In other words, Bernard values Plato’s Timaeus here not merely for its insights into mathematics or even the structure of the universe, but also what this mathematics in the universe implies about the mimetic nature of poetry itself.

As many literary scholars have demonstrated, much of the European literary tradition follows suit in seeing the value of Timaean Platonism for the production of literature. This interest can be seen in such diverse authors as Alan of Lille, Chrétien de Troyes, and Dante.

While I would personally be loath to give up the access to the Platonic corpus that I possess, the medieval reception of the Timaeus constantly pushes me to reconsider how I am reading that corpus. Having a large corpus of texts actually places an onus on the modern reader to ask the question of where to place the textual emphasis: Which texts of Plato should be considered central (and which ones periphery) and why? For example, should Plato’s Republic be considered his last word on poets and poetry? What would happen if Plato’s Timaeus were given more weight?

C.S. Lewis once wrote in his introduction to On the Incarnation by Athanasius:

Every age has its own outlook. It is specially good at seeing certain truths and specially liable to make certain mistakes. We all, therefore, need the books that will correct the characteristic mistakes of our own period. And that means the old books.

These words about reading the great books can also apply to reading the old books as they were read by past readers. Understanding medieval readings of Plato might very well be a good counterweight to modern presuppositions about who Plato was and what he was about. How might the idea of Plato as both a mathematician and myth-maker transform our modern understanding of Platonism and its history?

Lesley-Anne Dyer Williams is a Professor for Memoria College’s Masters of Arts in Great Books program and graduated with her doctorate from the University of Notre Dame’s Medieval Institute in 2012. She was also the founding director Liberal Arts Guild at LeTourneau University. Her research focuses upon twelfth-century Platonism and poetry, especially Thierry of Chartres and Bernard Silvestris.

Lesley-Anne Dyer Williams

Public Humanities Postdoctoral Fellow

Medieval Institute

University of Notre Dame

For Further Reading:

Caiazzo, Irene. “Teaching the Quadrivium in the Twelfth-Century Schools.” A Companion to Twelfth-Century Schools, edited by Cédric Giraud, translated by Ignacio Duran, vol. 88, Brill, 2019, pp. 180–202.

Calcidius. On Plato’s Timaeus. Edited by John Magee, vol. 41, Harvard University Press, 2016.

Chenu, M. D. “The Platonisms of the Twelfth Century.” Nature, Man and Society in the Twelfth Century: Essays on New Theological Perspectives in the Latin West, translated by Jerome Taylor and Lester K. Little, vol. 37, University of Toronto Press, 1997.

Dronke, Peter. The Spell of Calcidius: Platonic Concepts and Images in the Medieval West. SISMEL edizioni del Galluzzo, 2008.

Gersh, Stephen. Middle Platonism and Neoplatonism: The Latin Tradition. Vol 1 and Vol 2. University of Notre Dame Press, 1986.

Hoenig, Christina. Plato’s Timaeus and the Latin Tradition. Cambridge University Press, 2018.

Murray, K. Sarah-Jane. From Plato to Lancelot. Syracuse University Press, 2008.

Reydam-Schils, Gretchen. “Myth and Poetry in the Timaeus.” Plato and the Poets, edited by Pierre Destrée and Fritz-Gregor Herrmann, Brill, 2011.

Somfai, Anna. “The Eleventh-Century Shift in the Reception of Plato’s Timaeus and Calcidius’ Commentary.” Journal of the Warburg and Courtauld Institutes, vol. 65, 2002, pp. 1–21.

Stock, Brian. Myth and Science in the Twelfth Century. Princeton University Press, 1972.

Wetherbee, Winthrop. Platonism and Poetry in the Twelfth Century. Princeton University Press, 1972.