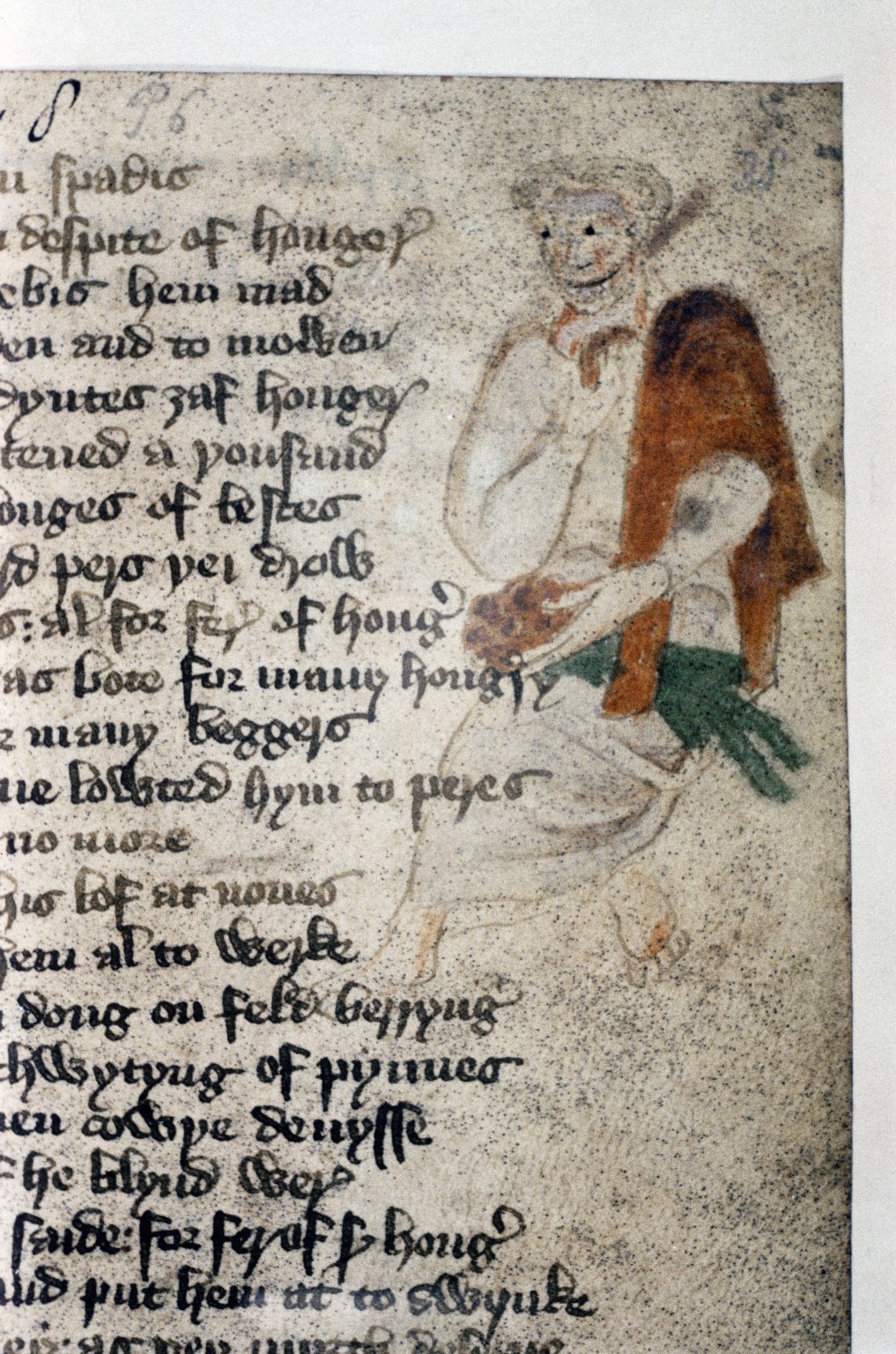

In one of the most moving additions to the C-text of Piers Plowman, Langland highlights the plight of impoverished mothers, who are some of the most vulnerable and underrepresented figures of his society:

And hemsulue also soffre muche hunger

And wo in wynter-tymes and wakynge on nyhtes

To rise to the reule to rokke the cradel,

Bothe to carde and to kembe, to cloute and to wasche. [1] (77-80)

Though these lines form only a part of Langland’s snapshot of working-class women, they poignantly convey the life of a working mother as she sacrifices her own well-being to feed her children, obeys the regulation of an infant’s nocturnal feeding schedule, and takes in domestic labour to make ends meet.

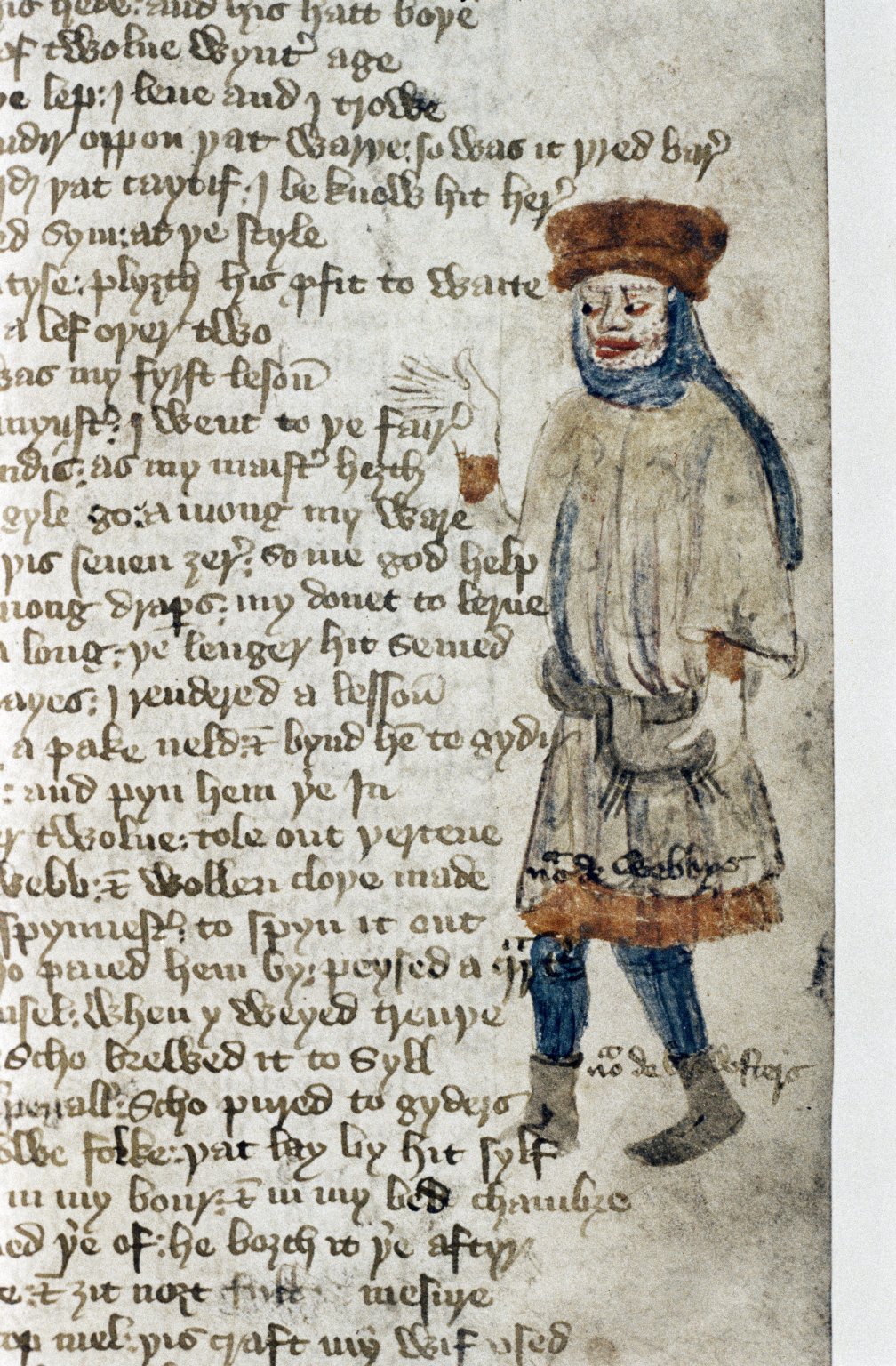

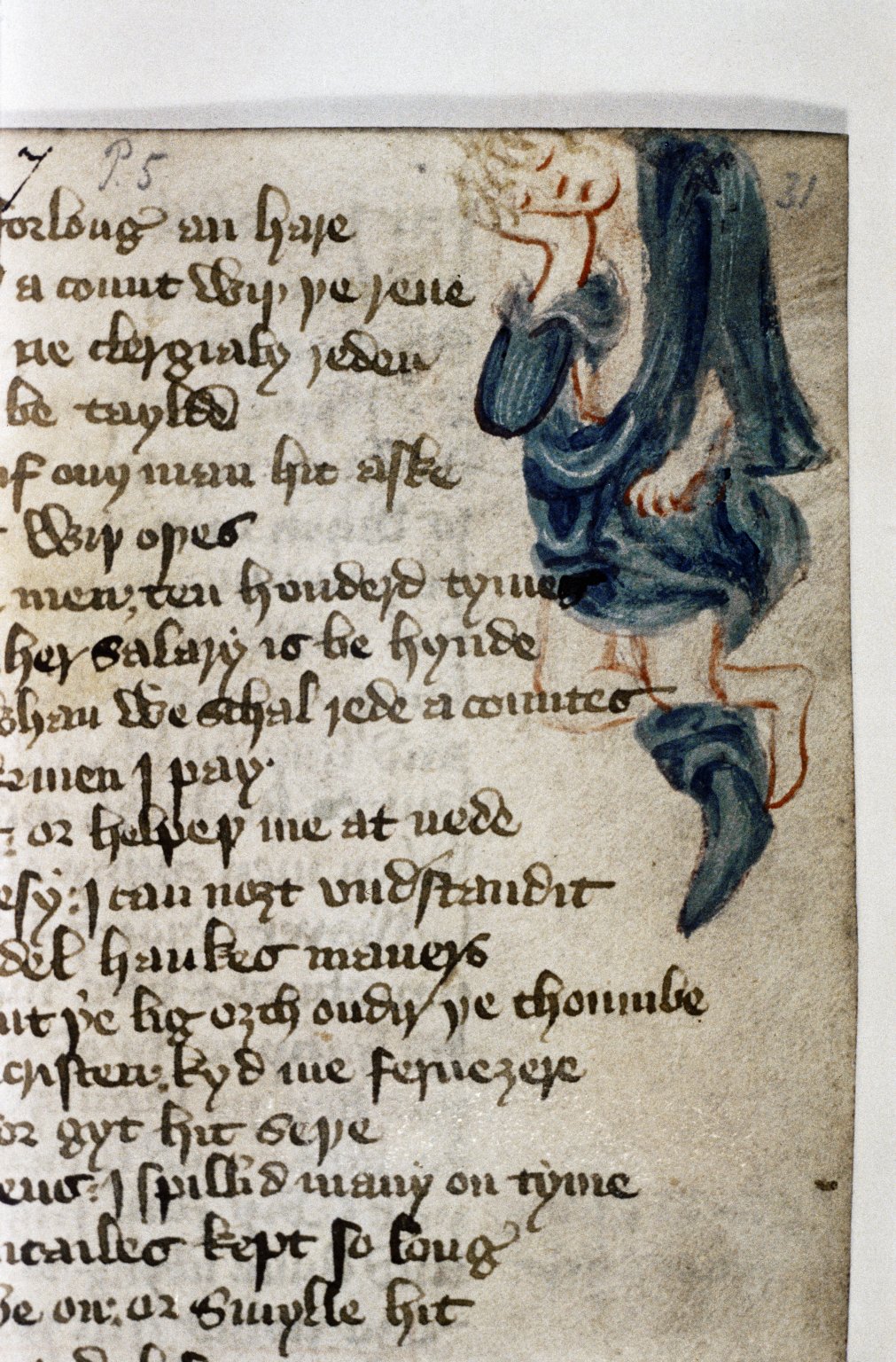

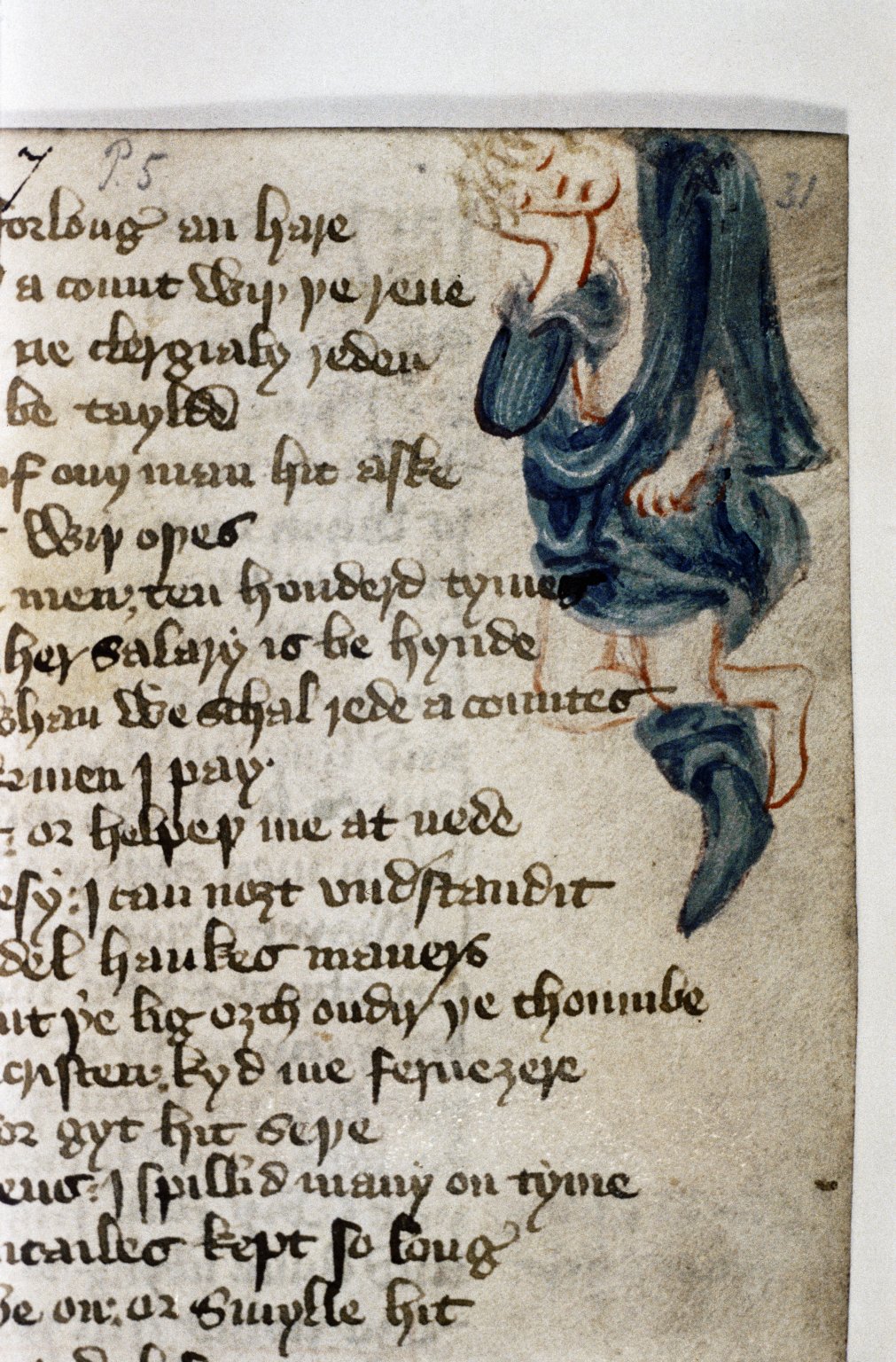

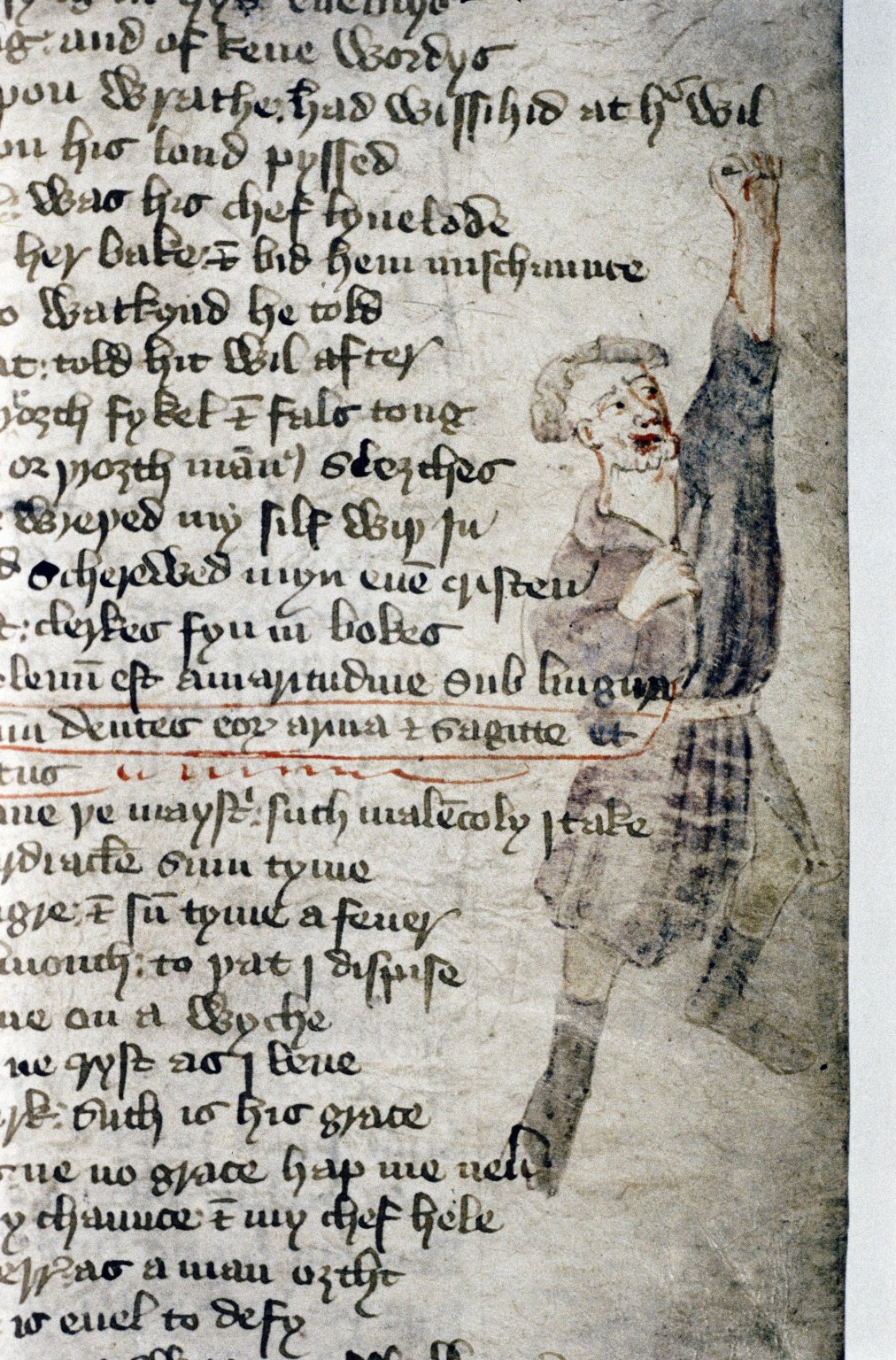

The passage excerpted above has been passed down through the Pearsall edition of the C-Text, but a little digging into the scribal variants across different manuscripts opens up a realm of possibilities for additional layers of meaning that could be added to the text. The scribe of the Cambridge University Library Dd. 3. 13 manuscript invokes a particularly intriguing possibility when he writes that these women were not “wakynge on nyhtes,” but “walkynge on nyhtes.”

‘Walking at night’ was associated with all sorts of immorality in medieval England, summed up in Chester Mystery Cycle when Jesus declares that “whosoever walketh abowte in night, hee tresspasseth all agaynst the right.”[2] Night-walking is specifically associated with sexual immorality by the Wife of Bath when she excuses her own desire to walk at night by saying that she is doing so to see the “wenches”[3] that her husband sleeps with (III l.397-398). Religious and secular legal discourses indicate that there was little distinction made in medieval England between women of “loose morals” and those who were involved in prostitution.[4]

In the Cambridge manuscript, then, there is a possibility that at least one scribe allowed for a moving portrayal of women forced by economic necessity into prostitution, even if he retain associations of immorality. Canon law made no allowances for such a thing, as the church viewed extreme poverty as a condition that led a woman into a life of prostitution, but not a mitigating factor.[5] On the level of the particular scribe, however, the addition of a single letter pushes us to consider the possibility that at least some readers could understand shades of complexity in a practice that is otherwise condemned, even by Langland himself.

When it comes to a poem with such a complex and enigmatic textual tradition as Piers Plowman, each manuscript bears an important witness to the text. Each scribal variant might get us a little closer to an authorial reading, but it also might give us insight into the ways the text could be misread or misunderstood by scribes and readers. Even if the reading in the manuscript bears little or no resemblance to Langland’s poetry, it may be the product of a scribe “elucidating the sense and significance in a text according to the priorities of their own period and culture.”[6] Even when a misreading is simply an error on the scribe’s part, it provides an example of how some medieval readers might have encountered and interpreted the text in ways that complement or contradict the authorial sense of a passage.

Leanne MacDonald

PhD Candidate

Department of English

University of Notre Dame

References:

[1] William Langland, Piers Plowman: A New Annotated Edition of the C-Text, ed. Derek Pearsall (Exeter: University of Exeter Press, 2008)

[2] “The Glovers Playe” from The Chester Mystery Cycle, ed. R.M. Lumiansky and David Mills (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1974), 244.

[3] From The Riverside Chaucer, ed. Larry Benson (Boston: Houghton-Mifflin, 1987). Ruth Mazo Karras argues that though Alysoun is not a prostitute per se, she uses language of commerce to talk about her sexuality and the practicalities of marriage. See Karras, “Sex, Money, and Prostitution in Medieval English Culture” in Desire and Discipline: Sex and Sexuality in the Premodern West, ed. Konrad Eisenbichler and Jacqueline Murray (Toronto: University of Toronto Press, 1996), 202.

[4] Karras, “Sex, Money, and Prostitution,” 211.

[5] James Brundage, “Prostitution in the Medieval Canon Law,” Signs 1, no. 4 (1976): 836.

[6] M. B. Parkes, Their Hands Before Our Eyes: A Closer Look at Scribes (Farnham: Ashgate, 2008), 68.