“We may have to turn around if the wind gets too strong,” our bus driver told me. It was pelting rain on the morning of Saturday, April 1, the day of the Medieval Institute-sponsored pilgrimage to Southside Chicago. The night before, a tornado warning had hit Notre Dame, and I thought, even when traveling by modern-day motor vehicle, pilgrims must brave tempests to reach their destination.

Happily, the weather did not deter our driver, and our busload of 50 people disembarked at the Cardinal Meyer Center to walk in the footsteps of Father Augustus Tolton, the first recognizably Black American Catholic to be ordained a priest. The members of our pilgrim band, ranging in age from their teens to their eighties, hailed from Saint Mary’s College, the University of Notre Dame, Holy Cross School, and two local parishes, Saint Augustine’s and Saint Pius. We represented a cross-section of academic disciplines and communities from around South Bend.

The journey to Chicago marked the end of the MI’s Pilgrimage for Healing and Liberation series. On my mind were lessons learned from the four webinars we hosted throughout the spring semester. First, the goal of the journey is to come home changed. Pilgrimage encompasses our experience en route to holy places and within sacred precincts, but it doesn’t end there. The pilgrim identity leaves an imprint that lingers once the journey is over. Muslims who make the hajj earn an honorific title when they return home, signifying that they have grown in wisdom from their sojourn to Mecca. In the panel discussion on “Pilgrimage in the Global Middle Ages,” Professor Mun’im Sirry shared that some Indonesian Muslims even take a new name to emphasize that the hajj has changed their very identity. Of course, our day trip to Chicago was not as momentous as a once-in-a-lifetime pilgrimage to Mecca. Nevertheless, as pilgrims we set out with intentionality, desiring new energy to animate our work for racial justice.

The second lesson: how we go is as important as where we go. Professor Layla Karst, in the webinar on “Becoming a Pilgrim People,” described making a pilgrimage as a liturgical act that forms us as church. By journeying together, the pilgrim community makes God’s presence visible in the world here and now. Karst challenged those of us making the pilgrimage to become the church that the world needs today. Between 2021 and 2024, Pope Francis has invited Catholics into a synodal process designed to intensify communion, participation, and mission in the life of the church. By gathering a mix of students and community members, our group witnessed to Pope Francis’ vision for a church of encounter and dialogue between people of diverse cultures, generations, and life experiences.

The preeminent sacred site for Christian pilgrims is Jersualem, the place of Jesus’ death and resurrection. As Professor Robin Jensen explained, Christian pilgrimage dates back to the fourth century when the Church of the Holy Sepulchre was built. For nearly 2000 years, pilgrims have walked the Way of the Cross in Jesus’ footsteps. They recall the events of his Passion to draw close to him in his suffering. Death, though,is not the end of the story. The Holy Sepulchre marks the tomb from which Christ rose to new life, thereby liberating all creation from the power of death. What was once a place of trauma and violence has become sacred ground where compassion and freedom take root.

The destination for our pilgrimage was likewise the site of one man’s suffering and death. We walked to the bridge where Father Tolton returned by train from a priests’ retreat out of town. He began walking home in 105-degree heat but collapsed one block away from the station. Standing at the site of his collapse, we placed flowers and sang, lamenting the devastating impact of poverty, violence, and environmental racism on the people of Southside Chicago, where Tolton tended the sick and preached the Gospel. He died at a nearby hospital on July 9, 1897. In an American church that long denied his vocation because he was Black, Tolton persevered, shared his gifts, and made a way out of no way for Black Catholics. His life and ministry bore heroic witness to the promise of God’s Reign, where all are welcome and provided for abundantly.

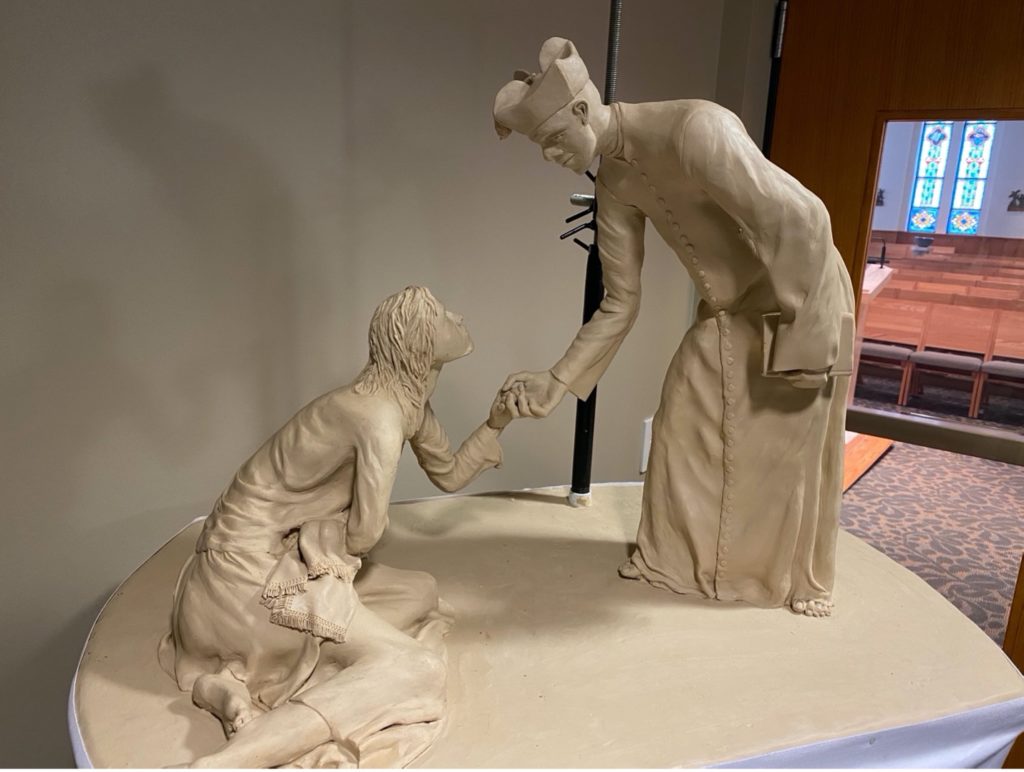

A providential surprise awaited us at the end of our journey. The founders of Warriors 4 Peace, an Indianapolis non-profit, were in Chicago the same day to meet with Bishop Perry, the promoter of Tolton’s cause. Warriors 4 Peace opposes gun violence and promotes peaceful change to honor the memory of Jack Shockley, who was murdered by handgun in 2020 when he was 24 years old. Jack’s parents adopted Fr. Tolton as the patron saint of their peace-making work, and an artist friend of theirs had created two sculptures of Tolton, which were on display the day of our pilgrimage. The life-size bust of Augustus Tolton generated a powerful sense of energy and presence. The icons reminded me of sacred art’s capacity to bring us face to face with the holy witnesses who have gone before us and still accompany us in the struggle for justice and peace.

Pilgrimages stage multiple encounters that have the potential to change people along the way. Through story, art, and places of memory, our pilgrim community encountered Fr. Tolton, a Black Catholic soon-to-be saint. We met our hosts at the Black Catholic Initiative of the Archdiocese of Chicago, who are carrying on the legacy of Tolton’s apostolate. We listened to the Shockley’s, who invited us into their grief. And throughout the day, while riding the bus and breaking bread together, each pilgrim encountered fellow travelers who had likewise given up their Saturday and defied stormy weather to make the journey. Pilgrimage both connects us with the religious practices of the deep past and forms us for a synodal church that can walk together into the future.

Annie Killian, Ph.D.

Public Humanities Postdoctoral Fellow

Medieval Institute

University of Notre Dame