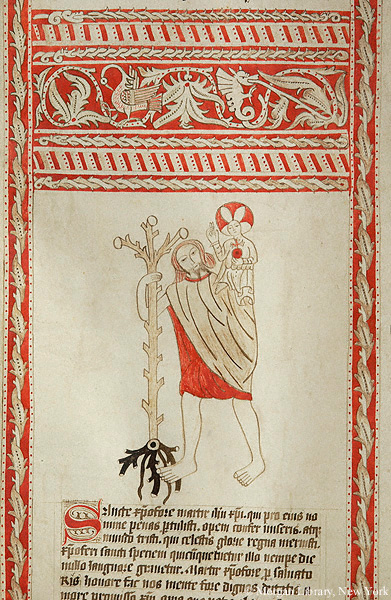

St. Christopher is a saint with an exciting etymological pedigree. The name Christopher is actually a brief description of one of the most famous stories about him: he is the Christ-bearer, from the Greek words Χριστός (Christ) and φέρειν (to bear or carry). Christopher, the story goes, was a new convert to Christianity and, as an ascetic spiritual exercise, undertook to wait by a river ford, carrying travelers across on his back. One day, a young child came along and requested passage.

As he carried the child across, the boy seemed to increase in weight until it seemed to Christopher that he carried the entire weight of the world on his back. This anomaly was explained when, on being challenged, the boy revealed that he was in fact the Christ child, and the weighty importance of his burden – responsible for both the creation and redemption of indeed the whole world – meant that this physical weight was a true reflection of its spiritual and symbolic importance. Depictions of Christopher, therefore, are easily recognizable, in depicting this famous story and rendering visible the pun of his name. Christopher is almost always shown stooped over, fording a river while carrying a small child on his back.

While this iconography is the most frequent and prevalent representation of Christopher, it is not, however, fully consistent with how the saint is represented in some of the earliest medieval descriptions of his story. Christopher is perhaps able to bear such a weighty burden because he is no ordinary man, but a giant in strength and stature. He was a convert to Christianity, coming from a country somewhere in the mysterious east – a region that, in medieval chronicles, romances, and travel writings, was frequently asserted to be the home of wonders and so-called “monstrous races,” mysterious peoples with strange customs and bizarre bodies: cannibals, men with ears like fans or faces in the center of their chests.

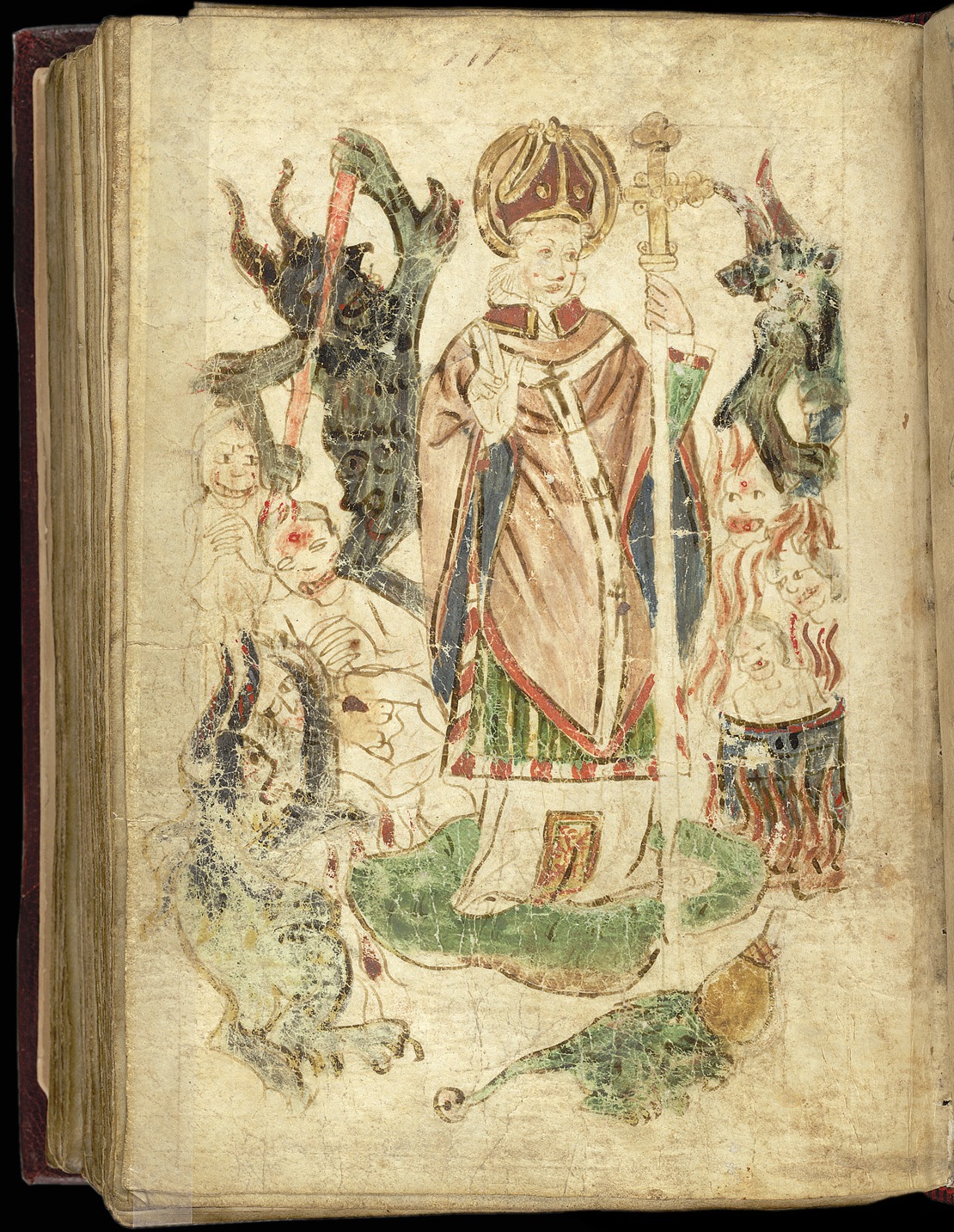

Among these strange peoples were the cynocephali, the dog-headed men, and it was to this race that Christopher was sometimes said to belong. In Mandeville’s Travels, one of the best-known of the travel narratives in the English traditions, a race of dog-headed men are described who are a fascinating combination of the fierce and the cultured: “Men and wymmen of that contre [country] hath houndes hedes [heads] and they ben resonable and they worshipeth an oxe for her [their] god and they gon [go about] alle naked save a lytel cloth byfore her [their] privyteis and they ben good men to fiȝt [fight] and they beren [carry] a great targe [shield] with wham [which] they coveryn alle her [their] body and a sper [spear] in her honde [hand].”

Despite their bestial appearance, they have “reason” and an apparently well-developed religion (although one, to Christian sensibilities, misguided). Largely naked, they are still human enough to wear loincloths and carry weapons – and when they defeat an enemy in battle, they take the prisoner to their king, “a gret lord and devout in his faith,” who wears a prayer necklace the author compares to a rosary.

Such a religiously-minded race, indisputably and terrifyingly “other,” but strongly mirroring the familiar, seems an appropriate match for St. Christopher. Being physically strong himself, one version of Christopher’s story goes, he decided to seek out and serve the strongest king he could find. But a powerful human king still stood in fear of the name of the devil, and when Christopher then sought out Satan as clearly the more powerful lord, he was likewise disappointed to find his new master frightened by the Christian symbolism of the cross. So finally he decides to serve Christ instead, as clearly the most powerful. In this version of the story, Christopher is cast in the role of a virtuous outsider, and his bestial appearance makes him an even more powerful spiritual exemplar, while the conclusion of the tale reassures the faithful of Christianity’s superiority, obvious even to someone not quite fully human.

Nicole Eddy

Postdoctoral Research Associate

Medieval Institute

University of Notre Dame