[This post was written in the spring 2018 semester for Karrie Fuller's course on Chaucer’s Canterbury Tales. It responds to the prompt posted here.]

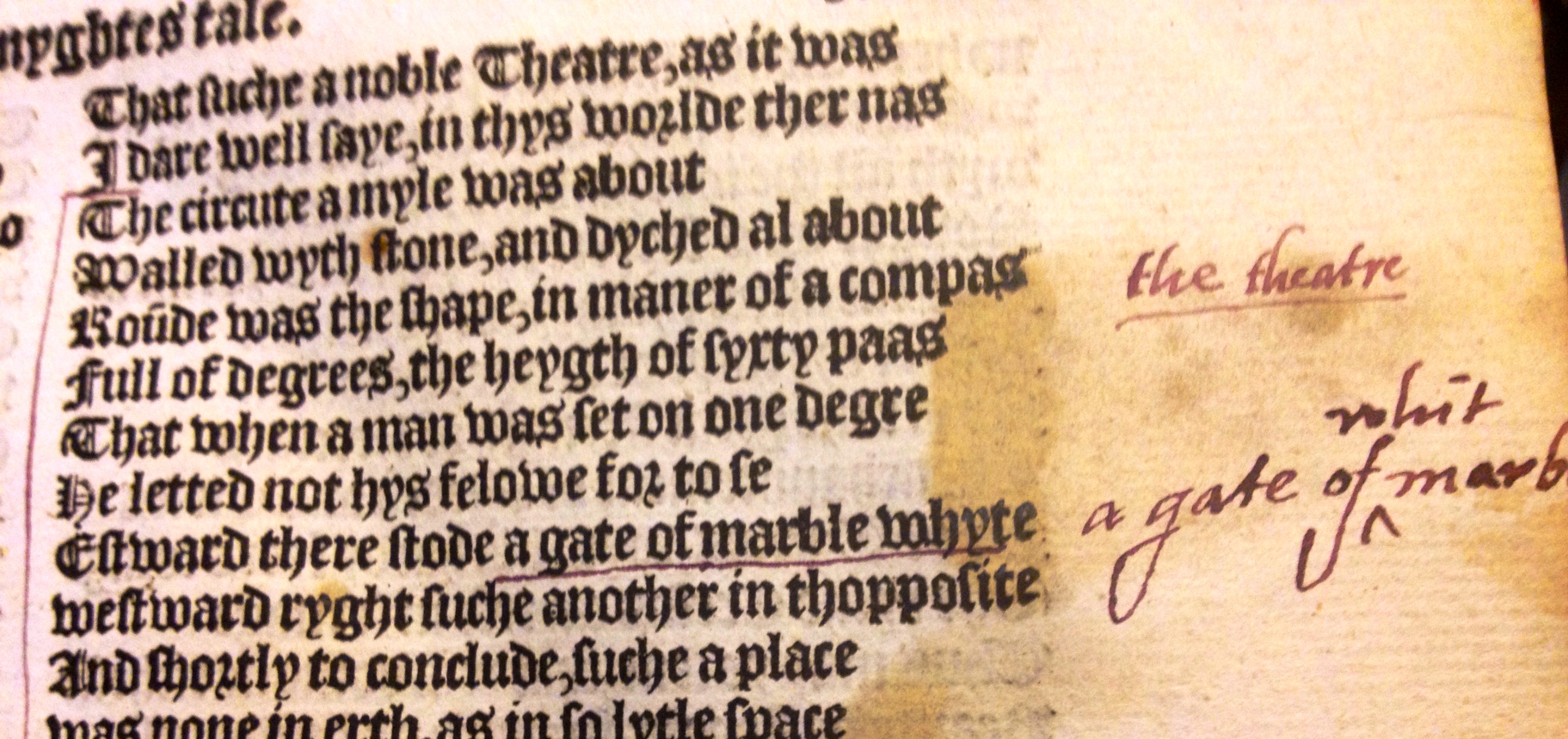

Courtly love, as described by Chaucer in his Canterbury Tales, consists of a series of rigidly-defined criteria by which a man may rightly pursue a woman. In such pursuit, it is not uncommon for a man to become infatuated with a woman to the point of physical illness. He admires her from afar as she becomes the sole object of his gaze; the entire energy of his being is directed towards contemplation of her beauty. This dynamic may progress significantly without any direct reciprocation from the female party. In Chaucer’s “The Knight’s Tale,” Emily endures the reality of courtly love to the point of abject suffering. (For a further analysis of the female voice in Chaucer’s tales, consider reading Ashtin Ballad’s Emily’s Modes of Expression in the Knight’s Tale- A Precursor to the #MeToo Movement). Several hundred years after the writing of The Canterbury Tales, Michel Foucault offers in his Discipline and Punish consideration towards a prison construct termed the ‘panopticon’. In this building, a fortified guard tower at the center of a circular room looks out upon rows of prison cells stacked against its perimeter. The windows of the central tower are tinted so as to prevent the prisoners from knowing whether or not they are under observation at any given moment. This dynamic instills a latent sense of paranoia within the prisoner and subjects them to a power relation which renders them unable to resist the the penal system above them. Between these two works appears a space for courtly love to exist in relation to the construct of the panopticon. With Emily’s character as a grounds for consideration, the following post will explore the extent to which courtly love suppresses the female will by means of persistent observation and imposition of external force.

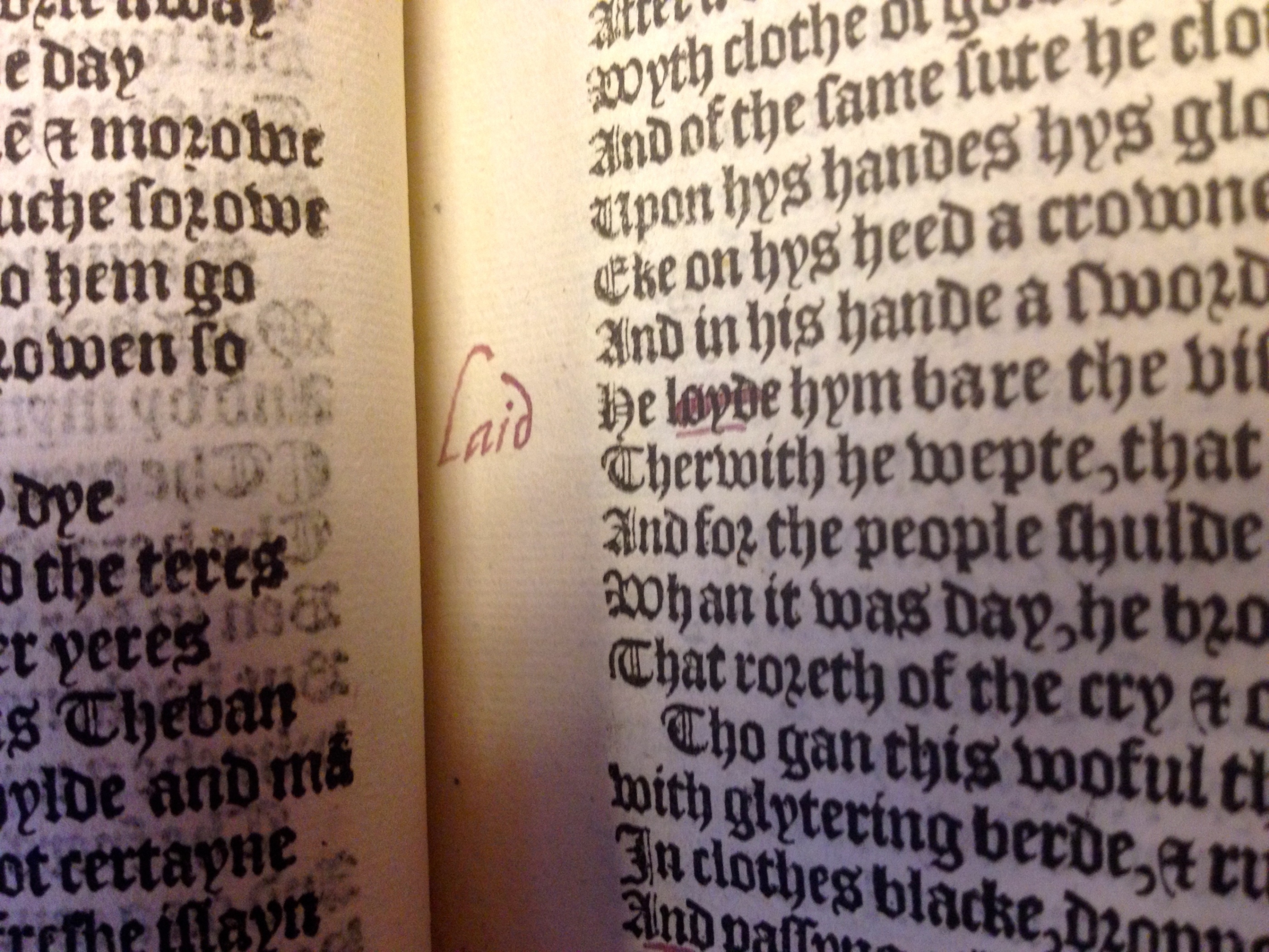

While observation from afar comes to constitute a significant theme in “The Knight’s Tale,” its practical application is inverted with respect to the work of Foucault. In effect, it is the prisoners who observe a free subject rather than enforcers of the penal system who gaze upon a prisoner. Chaucer details Palamon’s first encounter with Emily in writing:

And so bifel by aventure or cas* (it happened by chance or accident)

That thurgh a window thikke of many a barre

Of iren greet and square as any sparre* (beam)

He caste his eye upon Emelya (ln. 1074-1077).

Here, Palamon and Arcite conduct their observation from a point of concealment imposed against their mutual will. While the physical structure of the prison operates at a base level against them in their observation-power exchange with Emily, the Foucaldian implications of their situation work such that power weighs in their favor. Though Palamon and Arcite are traditional prisoners in the immediate sense, Emily here occupies the role of the panopticon prisoner. Her status as a young woman of consequential birth renders her a conventionally attractive subject of the male gaze. She is, however, entirely unaware of her sustained observation and subsequent fetishization by the palpably-bored Palamon and Arcite. (For an alternate exploration of love in Chaucer’s work, consider reading Nicole Matthias’ What is love, Or Chaucer as Related to Modern Views of Love in Literature).

Further, the role of the Gods in Chaucer’s work seem to embody the indifferent nature of the penal system with regard to the will of its prisoners. Foucault, a significant critic of Western prison practice in the 19th Century, argued that prison systems employed methods inconsistent with the personal development of prisoners. As a consequence of this, recidivism abounds and the penal system as a whole devolves into a self-indulgent cycle of discipline and punishment. Here, there seems to be a tension between an individual’s free will and a near-supernatural sense of predestination towards a certain fate. Chaucer employs this mechanic in the pseudo-smiting of Arcite following his victory in battle. In granting such a great degree of power to the fickle hand of fate, Chaucer emphasizes Emily’s own helplessness to resist the power structures above her. Not only is she impotent in the face of the male presence which observes her and dictates her future, a further unseen element toys with the very fate of mortals and casts their affairs in a perpetual state of uncertainty.

In summary, Chaucer’s work in The Canterbury Tales maintains relevance beyond its value merely as a surviving fourteenth-century work of literature. Granted appropriate consideration, many tales serve as a fruitful ground for application of modern theory. In Chaucer’s time, the panopticon was hundreds of years from conception. The very notion of an advanced, sprawling penal system seems beyond the scope of possibility for Chaucer’s own context. Still, in producing nuanced works such as “The Knight’s Tale,” Chaucer effectively allows for his work to carry significance well into the modern age.

Connor Dunleavy

University of Notre Dame