[This post was written in the spring 2018 semester for Karrie Fuller's course on Chaucer’s Canterbury Tales. It responds to the prompt posted here.]

I’m not going to try to talk you out of social media. Sure, it might be a bad habit to spend fifteen minutes scrolling through Instagram before I get out of bed in the morning, and I don’t want to know how many hours of my life I’ve spent procrastinating on Facebook, but I’m no Luddite: this is the world we live in now.

While I’ll never be one to condemn social media, I do think it’s important to realize that these social platforms, like all physical platforms, are stages. The versions of ourselves that we put forth online are heavily revised; we’re acting out parts and exaggerating the best features of our lives. Especially with the characteristic immediacy of stories on a growing number of platforms, such as Snapchat, Instagram, and Facebook, it can be difficult to discern just how authentic these put-forth “realities” are. In our incessant need to capture all things glamorous, the selves that are featured online are caricatures at best.

Though the stream of images, posts, and witty captions hold some validity, social media is also distortive through the control we have over what is spotlighted and what is left to the shadows.

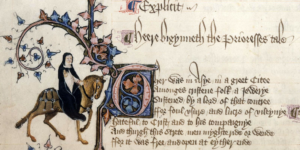

Yet, this obsession with self-presentation is not a new phenomenon, and such careful consideration of appearance is evident even in the Middle Ages. Chaucer’s Canterbury Tales illuminates this preoccupation with image and reputation. Though several members of the pilgrimage suffer because of their lack of genuineness in their professions, the Prioress attempts to mask her emphasis on image as she acts out the role she is expected to play in society. That is, a prioress should be a pious figure who inspires others to act virtuously. The other pilgrims expect the Prioress to be singularly devoted to religion, but as demonstrated by her description in the General Prologue, the Prioress has other wordly fixations. Similar to modern vanities, the Prioress is preoccupied with her appearance. She is described as being able to speak elegant French and as wearing extravagant beads and a brooch, giving her a rather noble and proper disposition rather than the humble servitude one might expect from her.

Along with this desire to appear noble, is the Prioress’s love for food. She appears to pay no regard to her vows of poverty and indulges herself on luxurious feasts to demonstrate her understanding of table manners, letting “no morsel from hir lippes falle, ne wette hir fyngres in hir sauce depe” (Chaucer A127-128). Even the Prioress’s name, Madame Eglantine, is a reference to her superficiality. Eglantine is a type of rose, characterized by its sweet scent. This symbol indicates a lack of permanence, as the scent and bloom of the flower will inevitably flash-fade. Unlike spirituality, material obsession will not last and as much as the Prioress attempts to cultivate her image, her beautiful appearance and noble facade are easily stripped away.

Because the Prioress is so concerned with how others perceive her, she tells a moralizing and evangelical tale in favor of Christianity that ticks off all the boxes: she opens with a prayer, narrates a story about an innocent martyr, and emphasizes the importance of the Virgin Mary. Aside from the troubling anti-Semitism, the Prioress’s section is too perfect– a performance piece meant to draw attention to her religiosity and reinforce her positive appearance. The tale functions as a mask for the Prioress to hide behind, and she presents the most idyllic version of herself to the other pilgrimage members. Much like the heavily-filtered, highlight reel of our social media lives, the Prioress uses her tale to present herself as she wants to be seen. Like social media users of the modern day, the Prioress is obsessed with appearances, and only wants others to see the best version of her possible.

However, it is also unfair to say that the Prioress’s religiosity is completely fictionalized, as her reliance on religious imagery is too extreme to be feigned. The tale follows a young boy who goes forth singing O Alma redemptoris in praise of the Virgin Mary. This song is pure and innocent in comparison to the Jewish ghettos full of the “cursed folk of Herod” (Chaucer G 574). The Jews feel that their religion is being threatened by Christian influences as indicated by their reaction to the boy’s song when some of them conspire to murder him. Yet, evil does not prevail, and ultimately, the Jews are powerless against Christianity. The boy continues to sing the Gregorian chant despite having his throat slit.

Not only does this part of the tale possess an evangelical and moralizing message, it also legitimizes the Prioress’s religiousity. She is clearly knowledgeable of religious works, especially Marian liturgical traditions, but furthermore, her tale follows the traditional arc of a literary representation of a saint’s life, a vita. Her knowledge of Christianity is also evident in her use of symbolism. The boy’s miraculous singing is possible because Mary slips a piece of grain under his tongue, akin to the Eucharist or Bread of Life, which would grant him eternal life.

This sanctification and overt moralizing message are typical of what the Prioress should believe. The pilgrims expect her utmost concern to be evangelization and wholehearted commitment to Christianity. Yet, while the Prioress demonstrates her knowledge about Christ, it seems that her tale is too fitting to her role in society, orchestrated to further a stereotypical religiosity.

With the more authentic depiction of the Prioress in the General Prologue, it becomes apparent that the tale only figures a fragment of herself. Similarly, social media offers only a marginal representation of ourselves. Our posts on Instagram only advertise the best and most beautiful portions of our lives; our weaknesses are omitted. The Prioress mirrors this desire to maintain a certain image. Her tale is saturated with holy imagery because this is the filter she wants to use to present herself.

Unlike the purity exhibited by the martyr of her tale, the Prioress is consumed by a need for validation in her self-image. She is highly conscious of her appearance, which leads her to act in extremes. Everything she does is a performance. This puts tension between her love for grandiosity and her desire for piety. Much like this media-inclined world, only the extremes are capable of capturing attention, and the ordinary is dismissed. As the Prioress strives to highlight her virtues and mask her flaws, she represents herself in a way that is reminiscent of contemporary social media culture.

Angela Lim

University of Notre Dame

Works Cited

Boenig, Robert, and Andrew Taylor. “Geoffrey Chaucer: The Canterbury Tales.” (2008).

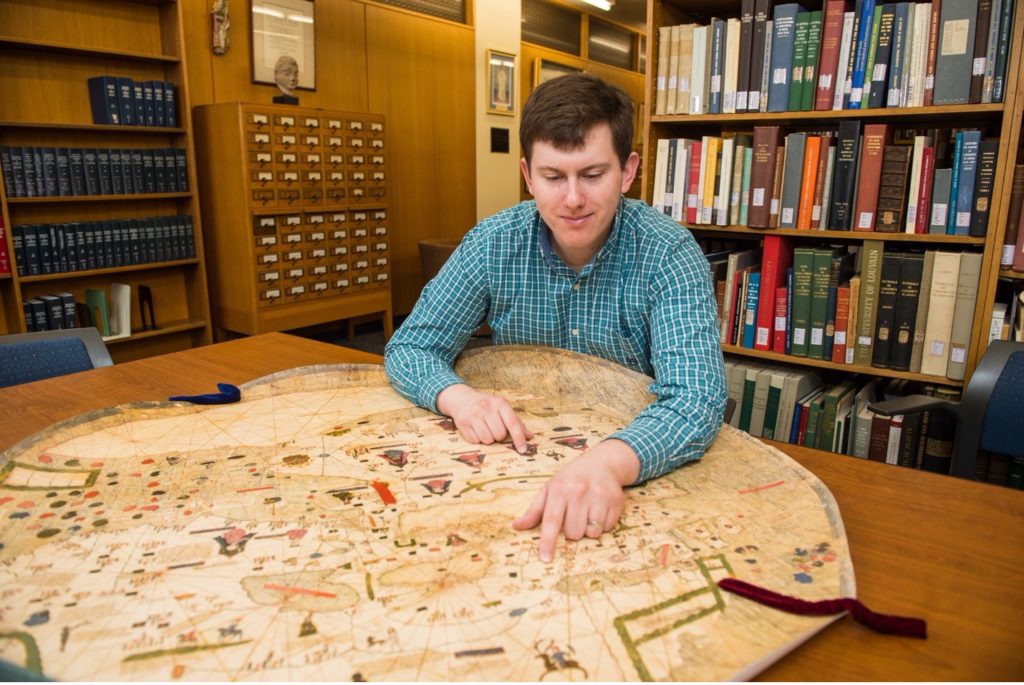

Chaucer, Geoffrey. The Canterbury Tales : The New Ellesmere Chaucer Facsimile (of Huntington Library

MS EL 26 C 9) / By Geoffrey Chaucer ; Edited By Daniel Woodward and Martin Stevens. Huntington Library Press, 1995.

“Instagram Moment.” ClevverNetwork. 2017. http://www.clevver.com/instagram-moment-2/

“I Think You Might Be Exaggerating A Little Bit.” Tenor. 29 Mar 2018. https://tenor.com/view/seth-meyers-exaggerating-alittle-bit-late-night-with-seth-meyers-late-night-gif-11511951

Law, George. “Scrolling Idle Hands.” Giphy. 6 Jun 2016. https://giphy.com/gifs/illustration-smartphone-scrolling-l41Ygr7sR5limRkek

“Zendaya Hair Flip.” Popkey. 2018. http://popkey.co/m/zJqep-zendaya-hair+flip