For many students, Sir Gawain and the Green Knight will likely be the first medieval text they are assigned to read. Frequently included in popular anthologies such as the Norton, Sir Gawain is a story that even non-medievalists such as myself are likely to have some degree of familiarity with. However, despite the poem’s familiarity Sir Gawain still holds a number of surprises in store for scholars and readers. In particular, I wish to discuss here what have come to be known as the four “fitts” the poem is commonly divided into.

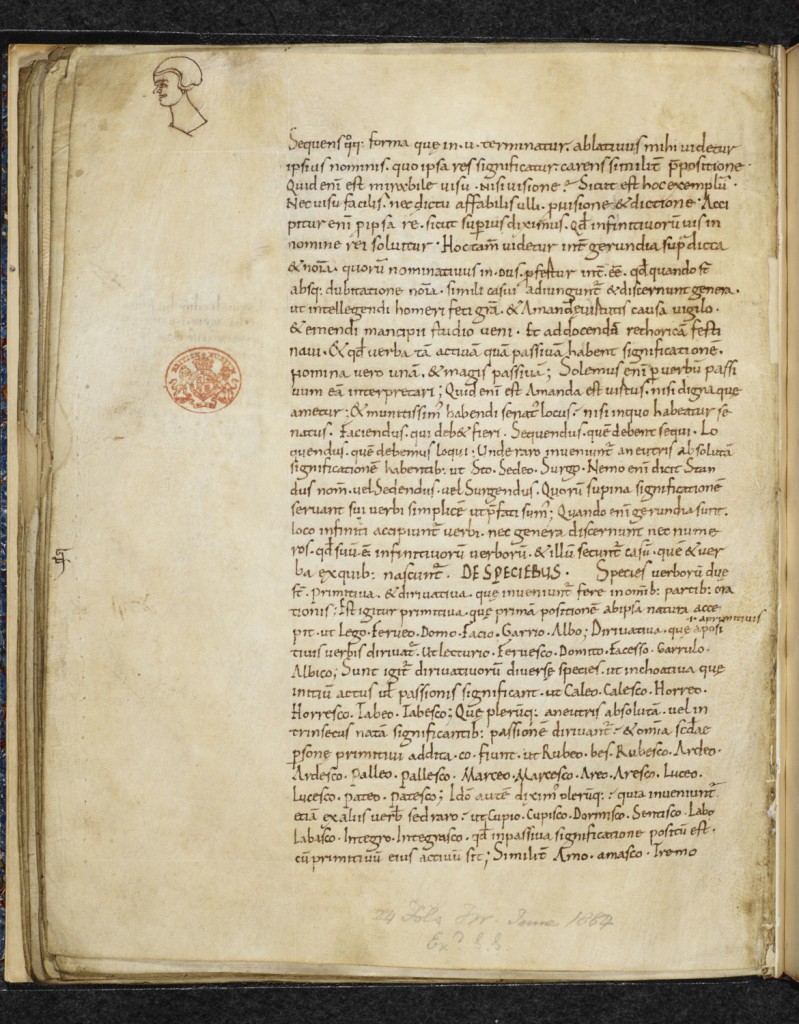

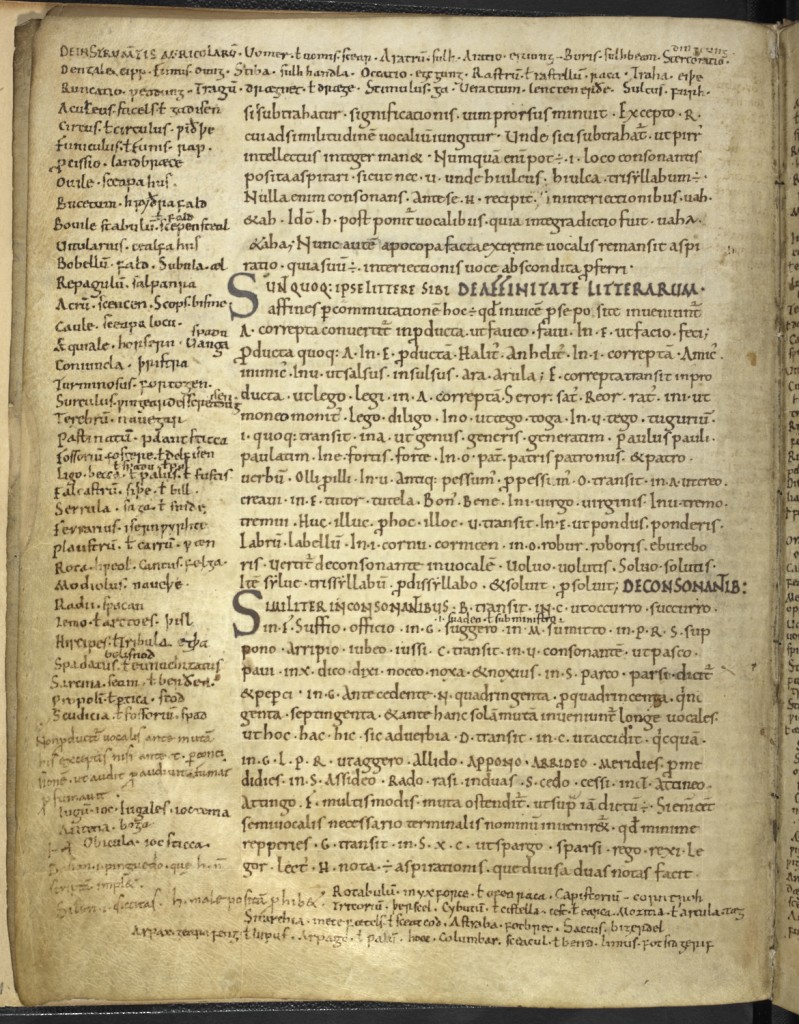

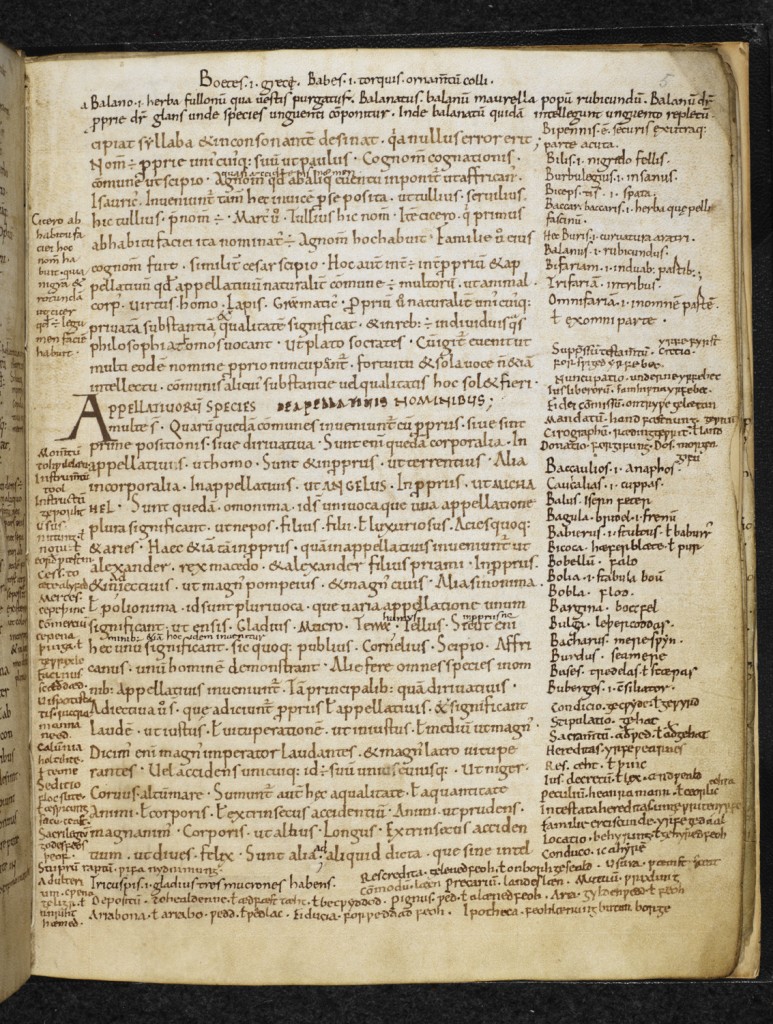

The text of Sir Gawain survives physically in just a single manuscript (Cotton Nero A.x.) in the possession of the British Library. The poem was rediscovered in the 1830s by Sir Frederic Madden, the Keeper of Manuscripts at the British Library and one of the foremost English scholars of his day. Madden edited and published the first edition of the poem, Syr Gawayne, in 1839. Here Madden inaugurated the tradition of dividing the text into four parts, or “fitts” as he termed them. This division has subsequently been unquestioningly received by most subsequent editors of the poem. In 1947, Laurita Lyttleton Hill became one of the first scholars to question the palaeographical justifications for Madden’s four-part division, writing, “One can only suppose that in the hundred years and more since Sir Frederic Madden’s ‘Syr Gawayne,’ tradition has solidified the published form of the poem into a mold that no one cares to disturb.”[1]

In the introduction to their 1925 scholarly edition of the poem J.R.R. Tolkien and E. V. Gordon note that “The four main divisions of the poem are indicated by large ornamental coloured capitals. Smaller coloured capitals without ornament occur at the beginning of lines 619, 1421, 1893, 2259.”[2] In her scholarship Hill dug deeper into these paleogeographic descriptions, casting doubt on whether Tolkien and Gordon’s descriptions of the capitals as “large” or “small” were entirely accurate, and on whether the degrees of the capitals’ ornamentation stands up to scrutiny as a justification for the divisions.

Ultimately, Hill advocated for a nine-part division recognizing all of the manuscript’s capitals as places of division. Hill ended her argument with the emphatic claim, “It has become evident, however, that there is no absolute four-fold division of Gawain. Such a division exists only in printed tradition and cannot be supported by any attentive examination of Cotton Nero A.x. or of the poem itself.” I have included at the end of this post Hill’s diagram showing at what points in the narrative the capitals recognized in her nine-fold division occur in contrast to Madden’s. Kathryn Kerby-Fulton notes of the nine potential divisions, “One could make several observations: first, the divisions closely parallel the spirit of the medieval narrative summaries marking progress through romances—these tend to mark knightly clashes, deaths, and miraculous events. Second, perhaps more profoundly, the medieval divisions mark moments of soul searching.”[3] Although the four-fitt division creates a recognizable narrative structure for modern readers, it perhaps does so at the expense of the potentially richer alternative of attempting to recover these earlier conceptions of narrative progression.

Most subsequent editions since Hill’s article up to the present day have maintained Madden’s four-part division; however, an enriching scholarly conversation has taken up the debate surrounding the question of the four-fitt division’s paleographic merits. Unfortunately, this debate has been largely absent from the paratextual materials of many modern editions, such as Simon Armitage’s popular translation (which has since been taken up and used by the Norton). Many of these editions do not attempt to justify or explain their decision to retain Madden’s four-part division; due to the significant nature of Madden’s intervention it seems like an error to avoid addressing this decision, as many of the poem’s readers will, as a result, remain unaware about the poem’s structural uncertainty. I hope that recent scholarly endeavors such as the Cotton Nero A.x. Project, which seeks to increase access to the manuscript by digitizing it, will help to resuscitate this scholarly debate and perhaps even inspire new editions of Sir Gawainthat adhere more closely to the manuscript’s structure.

| Division | Scribal Initial | Madden’s Division | Correlation with the Poem |

|---|---|---|---|

| I | S | Part I | The beheading test, part 1; the new year, the blow received, lines 1-490. |

| II | T | Part II | The year passes before the annual combat; the knight is armed: lines 491-618. |

| III | T | N/A | The pentangle, the character of Gawain; the journey; Christmas Eve Gawain’s prayer for guidance; Lines 619-762. |

| IV | N | N/A | The sudden appearance of the perilous castle; Gawain’s reception; Christmas festivities; the exchange winnings proposed and accepted; Lines 763-1125. |

| V | F | Part III | The huntsman host; the deer hunt; temptation 1; lines 1126-1420. |

| VI | S | N/A | The huntsman host; the boar hunt; temptation 2; the fox hunt; temptation 3; the magic girdle; Lines 1421-1892. |

| VII | N | N/A | The fox hunt concluded; Gawain asks for a guide; he bids goodbye to those in the castle: lines 1893-1997. |

| VIII | N | Part IV | New Year; the journey resumed; the ford perilous; the Green Knight appears: lines 1998-2258. |

| IX | T | N/A | The beheading test part 2; the blow returned; the connection of Morgan la Faye with the plot; Gawain returns to Arthur’s court: lines 2259-2530. |

Source: Hill, Laurita Lyttleton. “Madden's Divisions of Sir Gawain and the `Large Initial Capitals' of Cotton Nero A.X..” Speculum, 21, 1, 1946, pp 70-71.

Joshua Wright

PhD student, English

University of Notre Dame

[1] Laurita Lyttleton Hill, “Madden’s Divisions of Sir Gawain and the `Large Initial Capitals’ of Cotton Nero A.X..” (21:1), 67.

[2] V. Gordon and J.R.R. Tolkien, editors, Sir Gawain and the Green Knight. VIII.

[3] Kathryn Kerby-Fulton, Madie Hilmo, and Linda Olson, Opening Up Middle English Manuscripts. 59.