Margery Kempe did not like to talk about her visions.

That’s an odd thing to say about England’s queen of performative piety, who took her white clothing and loud wailing on intercontinental tour. It’s an even stranger thing to say about possibly England’s most famous medieval visionary.

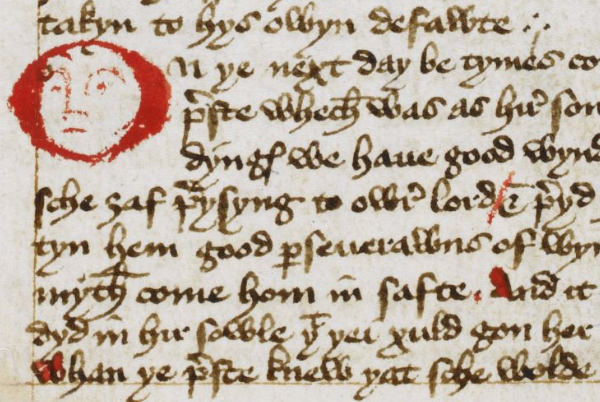

Indeed, Kempe’s revelations and auditions fill a substantial number of chapters in the fifteenth-century Book of Margery Kempe, an anthology of internal religious experiences and external adventures in the life of an eclectic laywoman. (The text claims to be dictated by the protagonist herself; I will be speaking here primarily of the two Kempes in the text, actor-author, whatever their relation to the person who composed the Book as a whole). [1]

Like many medieval women visionaries, Kempe recounts numerous types of visions. Most frequent are auditions, seemingly internal; sometimes only Christ speaks; sometimes it is a conversation. Kempe also experiences lavishly recounted “transporting” visions: for example, as a spectator of Christ’s passion, or a bridal ceremony. She also occasionally has access to knowledge about people’s afterlife fates. But despite the overwhelmingly important role that her “conversations and high contemplations” play in her spiritual life, she is rather reticent about disclosing them to the people she encounters.

It is most evident in the text when people complain about the heart of Kempe’s externalized devotion: how frequently she “burst out in violent weeping and sobbing” or “cry and roar” during sermons or while praying (or just encountering a mother and child on the road). [2] But while the Book has plenty of passages wherein Christ explicitly states the tears are his gift, Kempe does not defend herself by conveying this message. In one episode, the celebrant of that Mass experiences a similar sobbing breakdown which (according to the text) convinces him of her legitimacy; in another, she is (or allows herself to be) forced away from a hospital, which leaves her without a confessor or access to the Eucharist.

When Kempe is confronted about her behavior or describes animosity towards herself, the foremost topic is her “manner of living”—including her special manner of dress, special diet, habit of fraternal correction directed at…everyone, and above all her sobbing and wailing.

The disconnect between the Book’s descriptions and its protagonist’s silence is not total. Some people Kempe encounters do fill in the blanks, as when a Franciscan friar says she must be the famous (infamous?) woman who speaks with God. In Kempe’s recounting, however, his comment merits no response from her but does convince her that God’s instruction to go on pilgrimage was correct—which she does not reveal to the friar. [3]

More importantly, Kempe does sometimes initiate the announcement of her revelations. She discloses them to her confessor, her husband (at least, some of her revelations), her son: the people to whom she is closest. At God’s command (or so she insists), she reveals her conversations and extreme intimacy with Christ to a series of powerful clerical and charismatic figures: a bishop she has never met; two (or more) anchorites she has never met; university doctors of theology she has never met; a confessor she has never met before. According to the actor-narrator, she told them “to find out if there were any deception in her feelings. [4]

As numerous scholars have noted, her disclosure of her visions to official or sanctioned religious authorities invokes the doctrine known as discretio spirituum (discernment of spirits). [5] At the most basic level, discretio spirituum is scrutinizing apparently divine phenomena, such as visions or miracles, to determine whether they are truly divine or result from another cause. By the time in which the events of the Book of Margery Kempe take place, the 1410s, many theologians and Church leaders promoted a very specific application of this doctrine. It entailed both the need to prove that (mainly women’s) visions and miraculous asceticism were gifts from God instead of delusions from the devil or the human brain; and the struggle over who had the authority to determine what constituted enough proof.

The Book’s frequent declarations of Kempe seeking and gaining approval from a diverse array of Church leaders, including both Franciscans and Dominicans, illustrates a reasonably sophisticated handling of the doctrine, as Franciscans and Dominicans were often at odds over the legitimacy of a particular person or event. Somewhere along the way to the composition of the Book, someone recognized the importance, methodology, and unwritten problems of discretio spirituum.

There remains, however, the problem of the Book itself.

On one hand, you might observe that within the narrative, Kempe the protagonist sought out repeated verification of visions that (with the probable exception of her family) she shared with no one else. Moving around as a person in her world, she would have had no need to legitimize visions she shared with no one else.

On the other, you might point out that the full narrative is not present to any of the individuals Kempe encounters during her adventures. Only the listener or reader has access to it. And the reader (including any scribe along the way) does witness Kempe’s most intimate visions and would be looking for validation.

So, if the composer of the Book is willing to announce all types of visions experienced by the protagonist who apparently mirrors that composer—why does the Kempe of the text hide so many of her visions so intently?

[To be continued…]

Cait Stevenson

PhD in History

University of Notre Dame

—

[1] There is a substantial body of scholarship on the authorship of the Book and the relationship between the author, possible scribe or scribes, and protagonist of the text, including whether the Book qualifies as the first English-language autobiography. See, the debate between Nicholas Watson and Felicity Riddy in Kathryn Kerby-Fulton and Linda Olson (eds.), Voices in Dialogue: Reading Women in the Middle Ages (University of Notre Dame Press, 2005), 395-458. Many scholars use “Margery” to refer to the protagonist and “Kempe” to name the author; I have chosen to use “Kempe” for both because the general masculine tenor of Internet history discussions increases the importance of using non-infantilizing language to speak of historical women.

[2] Book of Margery Kempe, ch. 72, 83. For readers unfamiliar with Middle English, quotations are taken from Barry Windeatt (trans.), The Book of Margery Kempe (Penguin Classics, 1985). The original is available online through the TEAMS Middle English Text series.

[3] BMK, ch. 30.

[4] BMK, ch. 11.

[5] The foundational discussion on Kempe and discernment is Rosalynn Voaden, God’s Words, Women’s Voices: The Discernment of Spirits in the Writing of Late Medieval Women Visionaries (York Medieval Press, 1999), 109-153.