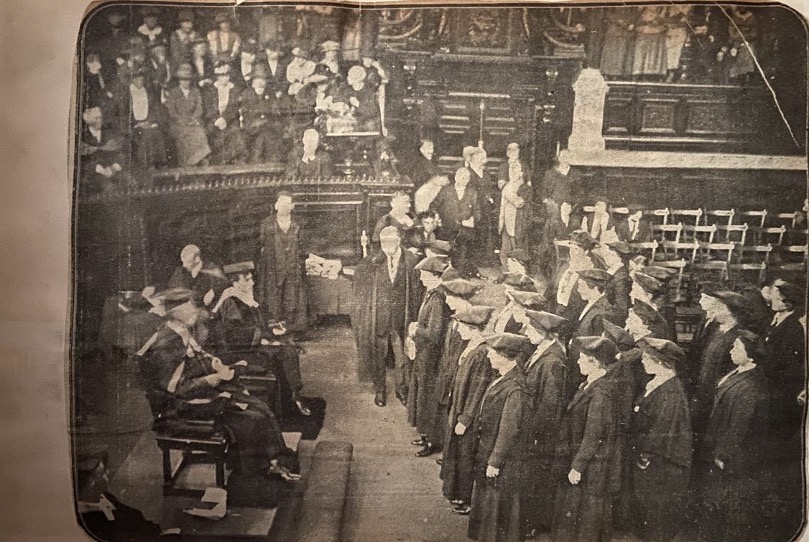

On October 14, 1920, the words, “domina, magistra” were spoken by the Vice Chancellor of Oxford University at the first ever graduation day for women. The grammatically feminine gender of these Latin words marked a major twentieth-century transition for university education. Among this first group of women was Dorothy L. Sayers. She was awarded a first-class MA degree in modern languages, a degree that she had earned in its entirety at Somerville College, Oxford University five years before but could not receive at the time merely because she was female. While her degree was in modern languages, at the time, and especially under the influence of the medievalist at Somerville College, Mildred Pope, an undergraduate degree in modern languages would have contained quite a bit of medieval studies, and this influence can be seen throughout her varied career. Whether Dorothy was writing advertisment campaigns for Guiness Beer (she did the Toucan campaign) or Lord Peter Wimsey mystery novels or radio dramas on the Life of Christ for the BBC or translating the Song of Roland and Dante’s Commedia, the Middle Ages seems to never be far from her mind.

Perhaps my favorite example from the Lord Peter mystery series occurs merely in her early characterization of Lord Peter in Whose Body? (1923). Dorothy Sayers admitted later than one of her motivations for writing Lord Peter, besides the need to earn money, was a certain kind of wish fulfillment during her own economically uncertain times. She imagines a character who has the means to live a life that she can only dream about. And what does Lord Peter do? He has his man, Bunter secure the purchase of rare books from an auction house while he follows up on a lead for his murder investigation:

“Thanks. I am going to Battersea at once. I want you to attend the sale for me. Don’t lose time—I don’t want to miss the Folio Dante* nor the de Voragine—here you are—see? ‘Golden Legend’—Wynkyn de Worde, 1493—got that?—and, I say, make a special effort for the Caxton folio of the ‘Four Sons of Aymon’—it’s the 1489 folio and unique. Look! I’ve marked the lots I want, and put my outside offer against each. Do your best for me. I shall be back to dinner.”

She even gives a footnote:

Aldine 8vo. of 1502, the Naples folio of 1477—”edizione rarissima,” according to Colomb. This copy has no history, and Mr. Parker’s private belief is that its present owner conveyed it away by stealth from somewhere or other. Lord Peter’s own account is that he “picked it up in a little place in the hills,” when making a walking-tour through Italy.

Notice that this isn’t an example of high-level scholarly influence. It is about the formation of her loves and passions soon after leaving Oxford. When she could fantasize about doing anything with money, she fantasizes about having enough money to buy expensive incunabula of Dante and de Voragine!

In addition to writing mystery novels, one of Dorothy Sayers’ earliest jobs after graduation was working at an advertising firm, the one for which she developed the Guiness Beer campaign. It appears from a paper given years later at a Vacation Course in Education at Oxford in 1947, “The Lost Tools of Learning,” that medieval studies may have given her a unique perspective on the advertising industry. She gave this paper almost twenty years after personally working in advertising (and writing Murder Must Advertise based upon her experience) but only a few years after the end of World War II, when the powers of propaganda in the modern world were first beginning to be fully recognized. With these experiences in mind, she writes:

Has it ever struck you as odd, or unfortunate that to-day, when the proportion of literacy throughout Western Europe is higher than it has ever been, people should have become susceptible to the influence of advertisement and mass-propaganda to an extent hitherto unheard-of or unimagined? Do you put this down to the mere mechancial fact that the press and the radio and so on have made propaganda much easier to distribute over a wide area? Or do you sometimes have an uneasy suspicion that the product of modern educational methods is less good than he or she might be at disentangling fact from opinion and the proven from the plausible?…Do you often come across people for whom, all their lives, a “subject” remains a “subject,” divided by water-tight bulkheads from all other “subjects,” so that they experience great difficulty in making an immediate mental connection between, let us say, algebra and detective fiction…between such spheres of knowledge as philosophy and economics, or chemistry and art?

Sayers suggests that the susceptibility of modern people to advertising and propaganda may be the result modern education. She even goes so far as to suggest that a return to the medieval trivium might be the best antidote! While realizing her proposal might be laughable, Sayers suggests that the issue is that “modern education concentrates on teaching subjects, leaving the method of thinking arguing, and expressing one’s conclusions to be picked up by the scholars as he goes along” whereas “medieval education concentrated on first forging and learning to handle the tools of learning, using whatever subject came handy as a piece of material on which to doodle until the use of the tool became second nature.” The medieval trivium of grammar, logic, and rhetoric was not really a series of “subjects” but rather a way to train students in the verbal arts, enabling them to then apply those arts to whatever subject they studied. Without this kind of medieval training, the modern person is enslaved to those with the ability to spin words most effectively.

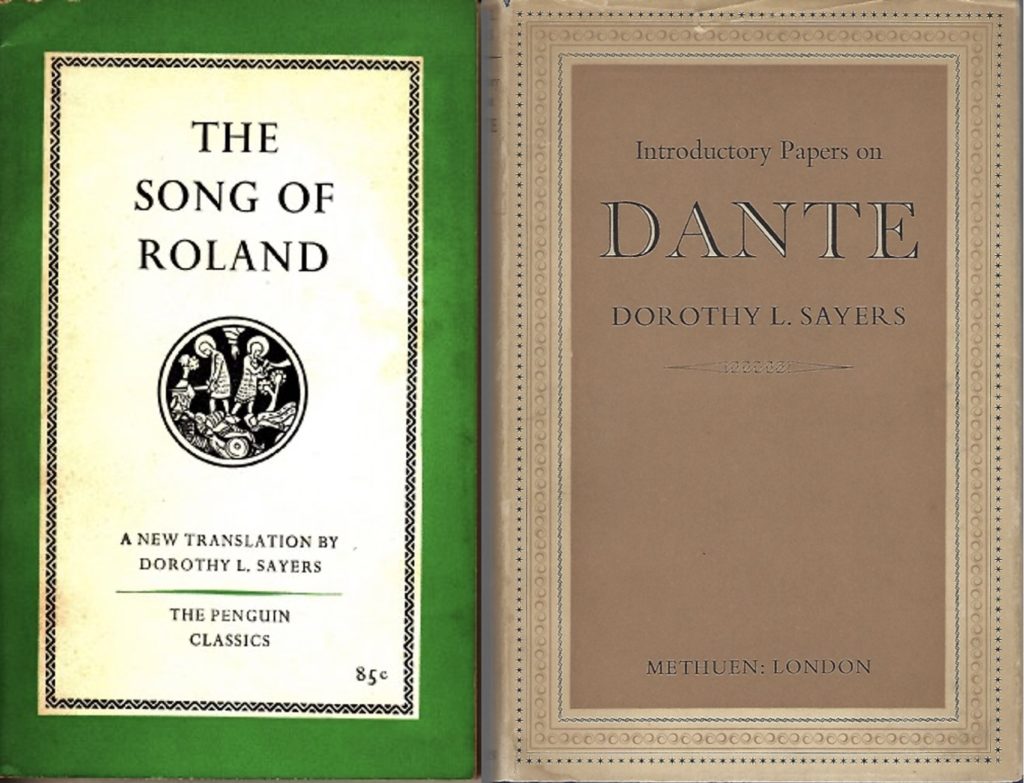

These examples from Whose Body? and “The Lost Tools of Learning” give only a taste of the way Sayers’ undergraduate education in medieval studies shaped her later work. More could be written about resemblances between medieval mystery plays and Sayers’ 12-part BBC radio drama on the life of Christ, The Man Born to Be King (and the way her medieval approach caused major controversy in 1942), not to mention her more serious scholarly pursuits translating The Divine Comedy (1949/1955)and The Song of Roland (1957). More could also be said on her remarks on medieval female brewsters in “Are Women Human?” (1947). What becomes clear, however, when one looks at her varied career is the impact of medieval studies upon the whole. The seeds of medieval studies sown at Oxford seem to have born fruit in her distinctively twentieth-century, modern life, one of the only times in history that a female graduate from Oxford University could be an advertiser, mystery novelist, radio dramatist, amateur educational theorist, and independent scholar.

Lesley-Anne Williams

PhD in Medieval Studies (2011)

Medieval Institute

University of Notre Dame

Selected Bibliography

Dante Alighieri. The Divine Comedy, Part 1: Hell. Translated by Dorothy L. Sayers. London: Penguin Classics, 1950.

Dante Alighieri. The Divine Comedy, Part 2: Purgatory. Translated by Dorothy L. Sayers. Penguin Classics, 1955.

Dante Alighieri. The Divine Comedy, Part 3: Paradise. Translated by Dorothy L. Sayers and Barbara Reynolds. Twenty-Seventh Printing edition. Harmondsworth Eng.; Baltimore: Penguin Classics, 1962.

Moulton, Mo. The Mutual Admiration Society: How Dorothy L. Sayers and Her Oxford Circle Remade the World for Women. First edition. New York, NY: Basic Books, 2019.

Reynolds, Barbara. Dorothy L. Sayers: Her Life and Soul. New York: St. Martin’s Press, 1993.

Sayers, Dorothy L. The Lost Tools of Learning. Louisville, Kentucky: GLH Publishing, 2016.

Sayers, Dorothy L. The Man Born to Be King: Wade Annotated Edition. Edited by Kathryn Wehr. Annotated edition. Downers Grove, IL: IVP Academic, 2023.

Sayers, Dorothy L. The Song of Roland. Penguin Classics. Harmondsworth, Eng.: Penguin Books, 1957.

Sayers, Dorothy L. Three for Lord Peter Wimsey: Whose Body? Clouds of Witness. Unnatural Death. New York: Harper & Row, 1964.

Whyte, Brendan. “Munster’s Monster Meets Dorothy’s Dragon: Lord Peter Wimsey Consults the Cartography of the ‘Cosmographia.’” Globe (Melbourne), no. 91 (2022): 61–74.